(MENAFN- Asia Times)

Famed CNN journalist Christiane Amanpour has made the news after refusing a demand by Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi that she don a headscarf as the precondition for an interview.

At a time when Iranian women are staging – at great risk, as witness the death in custody of Mahsa Amini – mass protests against mandatory hijab-wearing, Amanpour's stance is winning her a storm of bouquets on social media and the apparent approval of her employers.

“Amanpour had planned to probe Raisi on Amini's death and the protests, as well as the nuclear deal and Iran's support for Russia in Ukraine, but said that she had to walk away,” according to CNN .

Really?

Reporters routinely do things they may not like – from interacting with abhorrent sources to suffering injuries (even death) while covering a story. Given this,“had to walk away” seems extravagant.

Was Raisi's demand unreasonable? Certainly. But his unreasonableness is well established, if his hardline reputation and the ongoing violence in Iran is anything to go by. A CNN interview was a significant opportunity to put him on the spot – and the related issues represent a major divide in today's world.

Is Iran's leadership justified in promoting social harmony by enforcing a conservative religious code through its government, judiciary, police and society – thereby upholding sovereign tradition in defiance of vulgar, alien and Western-defined behavioral norms?

Or, are he and his colleagues and religious police a bunch of thuggish misogynists leveraging male-centric powers based on their interpretation of 7th-century religious texts – powers they deploy to brutally repress what should be acknowledged as universal, 21st-century female rights?

(An aside: I personally lean toward the second position. I state this not because my opinion particularly matters, but because I'd like to avoid the scheiss-sturm on social media that will be my lot if that is not spelled out. I digress.)

Amanpour – arguably the highest-profile face on arguably the leading global broadcaster – could have prodded Raisi on all these matters. They are important. Publics should be informed about them.

It is entirely acceptable for proponents of women's rights to ostracize Raisi, but Amanpour is a journalist, and journalists are required to engage. Needless to say, a Raisi interview was a chance many lower-profile, less-connected reporters and outlets would have leaped at. The key skillset of the journalist, after all, is“speaking truth to power.”

Amanpour declined to exercise that skillset. Certainly, Raisi's demand was unusual – his predecessors, whom Amanpour has interviewed, reportedly did not make it. Given the context of the violent suppression of ongoing protests, it was arguably repugnant.

But however indignant she may have been, Amanpour was hardly being asked to slaughter her firstborn; unlike Iranian women, she was free to remove her scarf immediately after interrogating Raisi.

So what was at stake? The story – taking Raisi to task on live television – or the personal rights principle, refusing a demand, while signaling solidarity with Iranian women?

The net result is that the wider world was robbed of what would likely have been an enlightening confrontation, because a journalist prioritized activism over journalism.

So comments on social media praising Amanpour as a superb reporter, when in fact she did not actually report, are bewildering. But this may be because she represents the pinnacle of a journalistic trend: the“star correspondent.”

Reporting vs opining

Millennial viewers of popular broadcast media may be astonished to learn that customarily in the past, reporters barely featured in their pieces: It was about the story, not the story teller. The duty was to report events, and the statements and actions of players; add necessary context and data; and seek expert analysis thereof.

Yet in an ongoing movement led in the US and beyond by Fox News and CNN, news delivery takes a back seat to anchors and journalists bloviating. To be sure, there is a space in journalism for bloviating – but that space is not reporting, it is opinion-editorial.

Reporters traditionally respected the journalistic maxim“Don't tell, show.” So strict was this principle that wire reporters were once forbidden to use adjectives (“The verb does the work”).

Reports in this style respect the intelligence of the reader/viewer, who is not told what to think. He/she consumes the story and makes up his/her own mind.

Op-ed is different. In this space, writers are free to be themselves, make arguments and lecture to the reader. But most outlets are led by reporting, not op-ed. A searing firewall exists – or used to – between the two.

In much contemporary broadcast journalism, that firewall has lost heat. Emotive interviewers talk as much as – or more than – their interviewees, while freely interrupting. Opinionated anchors rant, endlessly, to the camera. Star journalists make news rather than cover it.

(Mea culpa: As Asia Times' Northeast Asia correspondent editor, I primarily operate on the reporting, not the op-ed side. Here, I am – unusually – hurdling the firewall.)

True, a strong argument exists that true objectivity is impossible, so engaged – even impassioned – journalism is more honest.

The counter to that is that while perfection is unattainable, even impossible aspirations are worth pursuing. Striving for objectivity demands even-handed, opened-minded reportage and the suppression of personal bias.

But there are other factors in play – factors in modern discourse that extend beyond journalism.

Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi. Photo: AFP / Iranian Presidency / Handout / Anadolu Agency

Representation vs advocacy

Many who are opposed to Raisa applaud Amanpour for adopting a stance rather than granting him a platform. This bespeaks a growing problem enabled by social media: the practice of avoiding opinions or positions out of sync with one's own.

Take a sometime correspondent of this writer on social media who habitually states,“I read the first few paragraphs [of an article under discussion], but cast it aside because it was biased.”

Refusal even to acknowledge differing points of view is not just myopic, arrogant and dogmatic, it is anti-democratic. Democracies are founded on individual rights, and individuals embody diversity – diversity of gender, race, religion, experience, opinion, aspiration.

It is also stupid.

Most of the world is cast in shades of gray, but even in clear-cut cases of black and white, it is vital to comprehend the motivation, thinking and action of the other. A timeless principle of human competition is“Know thine enemy.”

Politicians inform themselves of the opposition's position before debating. Armies operate intelligence units to analyze enemies. Executives follow competitors' moves. Sportspersons study their opponents' form in pre-match preparation.

Today, many abandon this principle, denuding themselves of information.

That is another reason Amanpour's action was problematic. If you believe that women have a right not to wear headscarves, you need to hear the voice of Raisi and his ilk – ideally, through the filter of responsible journalism – if you are to counter it.

Representation, after all, is not advocacy.

Personal vs professional

Finally – in the unlikely event that this article passes across Amanpour's screen – permit me the following.

Christiane:

I hope you will accept the above as a professional, not a personal, critique.

Professionally, of course, this will not impact you in any way: Your position at the pinnacle of the profession is assured. In the personal space, I accept that you – a woman, of Iranian ancestry – are closer to this story than me. And naturally, you are within your rights to take offense at an interviewee.

Yet, for reasons given, I believe that the importance of the story outweighed your personal feelings toward scarves and demands.

But don't take my word for it. I invite you to mull what may be the gold standard of disinterested human-rights journalism.

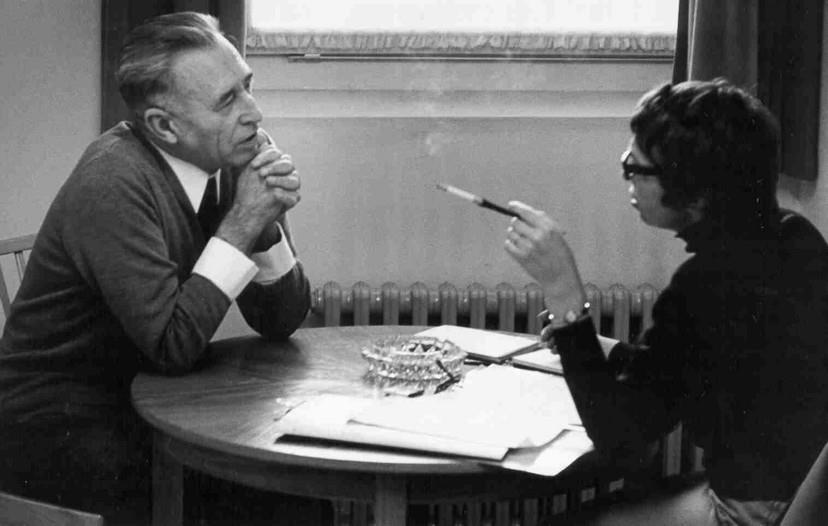

In 1971, Gitta Sereny sat down in a German prison with convicted felon Franz Stangl. Sereny was a reporter and author. Stangl was an officer who oversaw the most terrible place that ever existed: the largest of the Nazi liquidation camps, Treblinka.

Many confuse the concentration camps – horrific as they were – with the liquidation camps. Treblinka had no labor annex or factory complex, via which some inmates might, feasibly, have survived. It operated with one purpose: slaughter. Some 800,000 men, women and children, largely Jews, were gathered, gassed and incinerated there.

Over 70 hours, Sereny interviewed Stangl. She imposed extraordinary objectivity upon herself, writing,“I thought it essential … as far as possible unemotionally and with an open mind, to penetrate the personality of a man who had been intimately connected with the most total evil our age has produced.”

The day after the interviews concluded, Stangl – perhaps because he had finally been confronted with the depths of his guilt – died of a heart attack.

Getting the story – that is, getting her hands dirty by probing Stangl (and also some of his subordinates) over many hours – was a repugnant, distressing task for Sereny, who suffered psychological stress. But the end result delivered.

Sereny's output was an article for The Telegraph Magazine, and then the 1974 book Into That Darkness. It is a towering piece of Holocaust research, a troubling inquiry into evil and an important work for humanity to ponder.

Beyond its obvious value for the wider public, it is also a model for us in the profession: a lasting monument to engaged but objective journalism.

Journliast Gitta Sereny interviews ex-liquidation camp commandant Franz Stangl in a West German prison. Image: Facing History

Andrew Salmon is Asia Times' Northeast Asia editor. Follow him on Twitter @ASalmonSeoul.

MENAFN25092022000159011032ID1104920404