(MENAFN- The Conversation) The summer of 1985 is oppressive around the medieval Italian town of Gubbio. Thick heat is held captive in the wooded ravines and the windless slopes that climb and crawl across Umbria and on to the foothills of the Apennines. A short winding drive into the hills behind the town is the Libera Università di Alcatraz, a secluded retreat that is in the process of establishing itself as a gathering place for artists, writers and thinkers – a place where they can escape to nature and create.

In the Italian fashion, not everything is up and operating. Buildings stand half-finished. The swimming pool has been drained so a mural of a dragon can be painted on the bottom. But somehow the place works. Guests commune with their muses during the day, then congregate for meals on the terrace in the still, warm evenings to enjoy rustic fare prepared from local ingredients, washed down with red wine and tales from the assembled creatives.

The enterprise is run by Jacopo Fo, 30 years old and turning his hand to every aspect of the business, including the swimming-pool dragon. Until the artwork is finished, the pool can't be filled to give the guests some respite from the relentless summer heat.

Amid the dust haze and the fireflies that swarm the air, an unlikely gathering is taking place. Jacopo's parents are in town: Dario Fo and Franca Rame. They are setting up camp at Jacopo's enclave to rehearse a new play.

Fo and Rame are Italian cultural royalty. It is still 12 years until actor and playwright Fo will be recognised with the Nobel Prize for Literature, but he is already well-established as a national treasure. His groundbreaking work in commedia dell'arte flipped the nature of theatre. His plays present characters as grotesques who directly address the audience. Their anarchic asides are an assault on classical theatre's embrace of the heroic lead.

Fo's new play – Elizabeth: Almost by Chance a Woman – will be performed by a drama company from Finland. It is due to premiere at the prestigious Tampere Theatre Festival in a matter of weeks.

The play is incomplete.

Fo speaks no Finnish.

The Finns speak no Italian.

An interpreter is hired to make sense of Fo's instructions for the actors and the many rewrites that are taking place on a daily basis. Her name is Aira Pohjanvaara-Buffa. And since she is going to be camped out in the Umbrian woods for a month or so, she invites along her new partner. He is a respected but still mostly unknown British novelist by the name of Barry Unsworth.

At this point in his career, Unsworth had attracted a small but enthusiastic readership for his historical fiction. Seven years later, he will win the Booker Prize for Sacred Hunger, his novel set amid the horrors of the transatlantic slave trade.

So, from late June to mid-July of 1985, a future Nobel laureate and a future Booker Prize winner co-exist in the peace and bucolic calm of the Umbrian woods.

The rehearsals are a fiasco.

On the first day, the actors arrive drunk from the airport. The rehearsal stage is still to be built. Fo changes his script daily, hourly – often in the wings as the actors wait for fresh lines to be written for them. There are clashes between the traditional approach of the Finns and the anarchic methods of Fo and Rame. The lead actor is laid low with sunstroke. The director has brought his youthful boyfriend with him, and the young man starts to take an interest in some of the young women of the theatre company. Tempers run short in the unrelenting heat.

All the while, Unsworth keeps a meticulous diary, documenting the artistic approach of the enigmatic Fo, as well as the behind-the-scenes shambles of a production that seems destined for disaster.

For decades, the journal was forgotten. Bundled among the author's papers and correspondence, it eventually found a home in the archives of the Harry Ransom Centre at the University of Texas in Austin. The diary is in Box 12, Folder 6 of the Unsworth papers. Its observations are written in clear cursive in what appears to be blue biro, with occasional red annotations.

It makes for sometimes brutal reading.

The journal provides a first person account of the creative process of one of the 20th century's lions of theatre, in all its chaotic glory. Though it is a simple linear account of events, Unsworth manages to pen a compelling narrative and create fully realised characters.

Great promise

As with all such creative ventures, it starts with great promise.

But very quickly Unsworth senses some fragility in the foundations of the enterprise that lies ahead.

Even in his diary, it seems, Unsworth is not averse to a bit of dramatic foreshadowing. The future Booker winner is curious about the legend of Fo and whether the myth of the man measures up against the actuality. His descriptions, both of physique and psyche, are forensic.

Unsworth revisits this perplexing nature of Fo's character many times in the course of the journal. It is fair to say that the author is at first curious, then grows to admiration, and ultimately to great disappointment that the man is not the equal of the art that he produces. Fo's veneer is as thin as any stage setting, with much the same remit: to paint an image that reminds the audience of something majestic in real life, but which is itself a simulacrum, a construction.

When one artist views another whose work is in a different medium, it is often through the lens of their own craft. In Unsworth's case, he is fascinated by Fo's artistry on stage.

The play is set in the court of Elizabeth I, where the Virgin Queen fumes about Shakespeare's dramas satirising her reign and laments that her love, the Earl of Essex, is conspiring against her. As with much of Fo's work, it is a treatise on the misapplication of power. His career was founded on his scathing satire of authoritarian regimes, with works such as Accidental Death of an Anarchist (1970) and Can't Pay? Won't Pay! (1974), which earned him widespread regard as a champion of the working poor.

Dario Fo and Franca Rame with their son Jacopo in 1962. Wikimedia Commons Read more: guide to the classics: samuel beckett's waiting for godot, a tragicomedy for our times

God motif

That night at dinner, the two actors who had been excessively drunk apologise to Fo, and he warns them of the consequences if they transgress again. The play's director, Arturo Corso, arrives:

Also newly arrived is Corso's youthful boyfriend, Alfredo:

Unsworth's observations of Fo and his methods begin to adjust almost immediately. His diary entry for June 22 notes that the Finns face a tough taskmaster when rehearsals start:

Very quickly, Unsworth settles on a God motif in his observations of Fo at work and at play. He notes the characters in the performance are, through their actions and thoughts, questioning the words of God. Fo's constant editing and rewriting of his script, even during the course of the readings, is summarised as:“God changing the rules?”

It is at this point in the project that Alfredo reveals himself to be 16 years old. This prompts the journal observation from Unsworth that:

The following day, in a portent of things to come, a hot water bottle is fetched for Franca Rame who has collapsed after the morning's strenuous rehearsal.

In the midst of rehearsals stretching through long days without a break, Unsworth occasionally separates from the company and enjoys walks through the surrounding hills, heavy with flowering gorse, wild sweet pea, poppies and cornflowers. It is on these sojourns that he starts jotting notes for a possible novel, about an internationally famous playwright and actor, who buys up a sizeable piece of land and builds a theatre in the wilderness:

Ten years later, Unsworth's novel Morality Play, about a troupe of travelling players in 14th century England, is shortlisted for the Booker Prize.

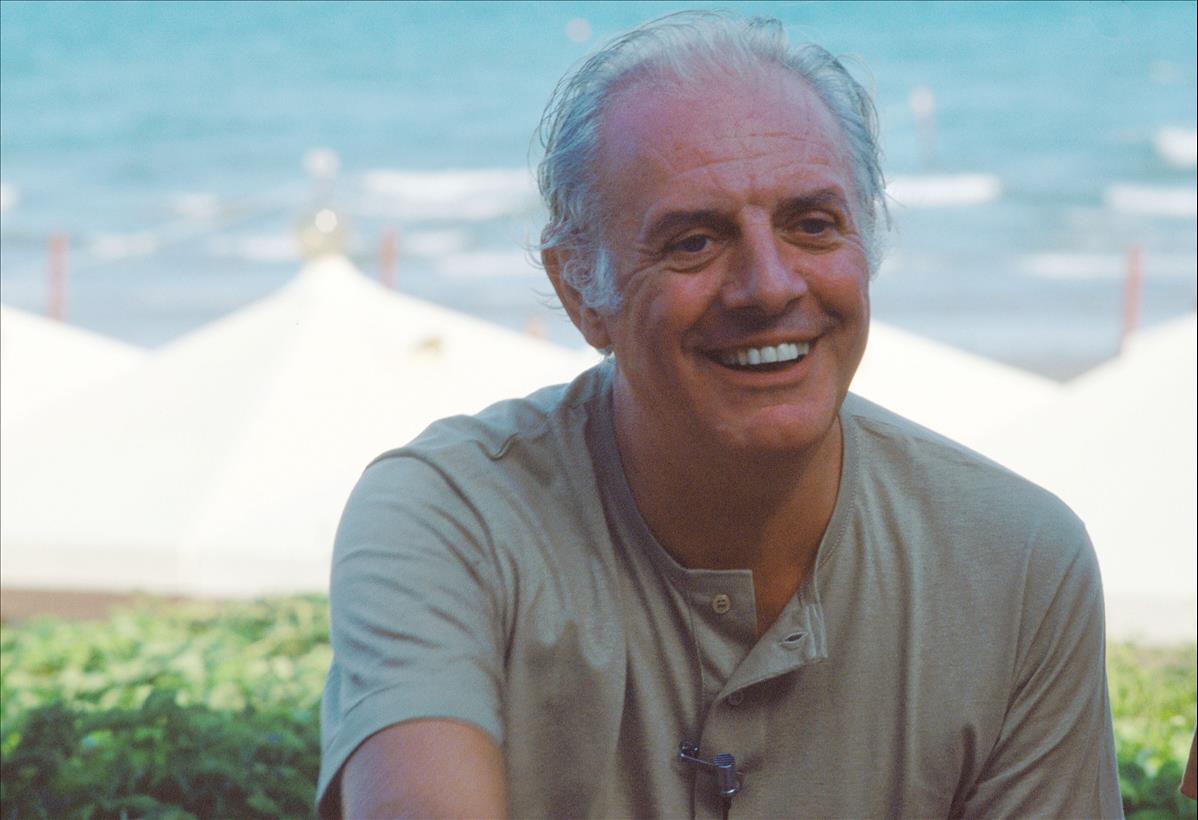

Dario Fo at Gubbio, 1988. Wikimedia Commons, cc by-nc-sa Growing tensions

By June 24, the growing tensions in the company are becoming obvious. Fo's constant script revisions and his reluctance to let Corso take on the full directorial role are causing stress among the players. Fo and Rame decide to decamp for a few days and leave Corso in charge.

For all of Unsworth's reservations about Fo's temperament and his substance, he is an unabashed admirer of his stagecraft. He describes Fo showing the actor playing the role of the Donnazza how to move:

In God's kingdom, a word from on high carries a good deal of weight. On June 25, Unsworth records:

Unsworth, however, is not easily guiled with words of praise. His works abound with thematic critiques of the neo-liberalism of the Thatcher years and the devastating impact her government's policies had on his native north of England. He has a northerner's disdain of bombast and pretension, and it is with this mindset that Unsworth regards Fo's everyday manner as being as performative as anything he does on stage:

At the same time, the actors are growing weary of this difficult Zeus-like figure in their ranks.

But even when Fo and Rame depart for a few days, the rehearsals are dogged with troubles. Payments due from Finland do not appear. The performers start drinking again. The actor playing the Donnazza is struck down with sunstroke, and one of the Finns must return home to attend their father's funeral. Director Corso accidently slashes his eyelid with a sharp thumbnail during an expressive flick of his hand and must conduct rehearsals with a broad bandage wrapped across his face. It is into this domain of instability that Fo and Rame return, only to ratchet up the workload.

The creative force behind Fo and Rame seems to be one of unending dissatisfaction with the status quo. There is constant tweaking, continual change.

Over the weeks, the rehearsals drag on. But there is progress as the date of the festival draws near: Actors begin to fully inhabit their roles; the script is finalised. The show is almost ready, and it is time for Unsworth to make his exit.

Ultimately, the author is left torn between Fo the artist and Fo the man. After a month in the master's presence, Unsworth leaves Umbria with the inklings of a new novel, an extensive first-hand account of the creative process of one of the twentieth century's most accomplished playwrights, and a bitter postscript in his journal, written on August 16 1985, five days after the show's premiere in Tampere:

The demarcation between artist and art will always be disputed territory. Does the strength of the work ever offset the weakness of the creator? Unsworth's final journal entry seems rooted in disappointment that a man with as much natural talent as Fo could also be capable of such base abuses of power, all the more unfortunate given his career was built on lacerating those who deny freedom to others.

A recent Turkish production of Dario Fo's play Elizabeth (2020). Wikimedia Commons Fiasko av Dario Fo

As far as can be determined, Unsworth wrote only once for public consumption about his summer in the Umbrian hillside: a piece for the Guardian in December 1985. The article, a preview of a documentary about Fo that was screening on Channel 4 that evening, is a broadly anodyne account of the Italian master's behaviour that month. It describes the shambles of the rehearsals, but masks Unsworth's contemporaneously recorded opinion of Fo's multiple shortcomings. He concludes the Guardian piece with:

And the performance itself in Tampere? If Fo's directing technique was confusing for the Finnish cast, the result on stage was no less confounding for Finnish theatregoers. The review in Hufvudstadsbladet, Finland's highest circulating Swedish-language newspaper, carried the bold headline: Fiasko av Dario Fo –“Failure of Dario Fo”.

Reviewer Marten Kihlman wrote that despite high expectations for the show, the audience reception was“lukewarm”:

The reviewer does dispense some praise – to the set designer.

And while he is scathing about the acting (“too loud”,“without charm”), he assigns blame in one direction only:“the ensemble should not be blamed for having a fatal theatrical ordeal: they follow Dario Fo's directive. And even masters sometimes miss.”

Comments

No comment