Migrant labor abuse bouncing back on Malaysia

SINGAPORE – Malaysia's major medical glove makers control more than two-thirds of the global market for a product that has been in emergency high demand amid the Covid-19 pandemic.

But many of the Malaysian companies that export personal protective equipment (PPE) to hospitals across the developed world now face modern-day slavery allegations for their widespread labor abuses.

Some of Malaysia's biggest rubber glove and palm oil exporters have recently had their goods blacklisted by the United States in response to third-party complaints of human trafficking, exploitation and forced labor of migrant workers in factories and plantations.

Malaysia is heavily reliant on migrant workers who toil in low-paid, labor-intensive jobs in the manufacturing, agriculture, construction and services sectors that are typically shunned by locals.

Around 2 million foreigners work in the country of 33 million, with those employed in the glove industry hailing mainly from Bangladesh and Nepal.

Now, glove makers are making unprecedented debt bondage repayments to tens of thousands of their current and former workers in response to a string of US Customs and Border Protection (CPB) bans on their products that have resulted in hundreds of millions of dollars worth of losses.

Under mounting pressure from international investors to comply with environmental, social and governance (ESG) guidelines, Malaysian glove makers have opened investigations into forced labor allegations and have undertaken related reforms – though some claim the US complaints have lacked merit and transparency.

YTY Group, the latest glove maker to be hit by the CPB's import ban, claimed in an interview with Asia Times to be in full compliance with International Labor Organization (ILO) rules on forced labor and said that the US border authority has, in effect, arbitrarily enforced sanctions against it without any prior consultation.

The US customs agency announced a so-called withhold release order (WRO) against YTY Group on January 28 based on information indicating the use of forced labor in its operations, making it the eighth Malaysian company subject to an import ban since September 2019. Six of the WROs remain active in Malaysia, more than for any other country except China.

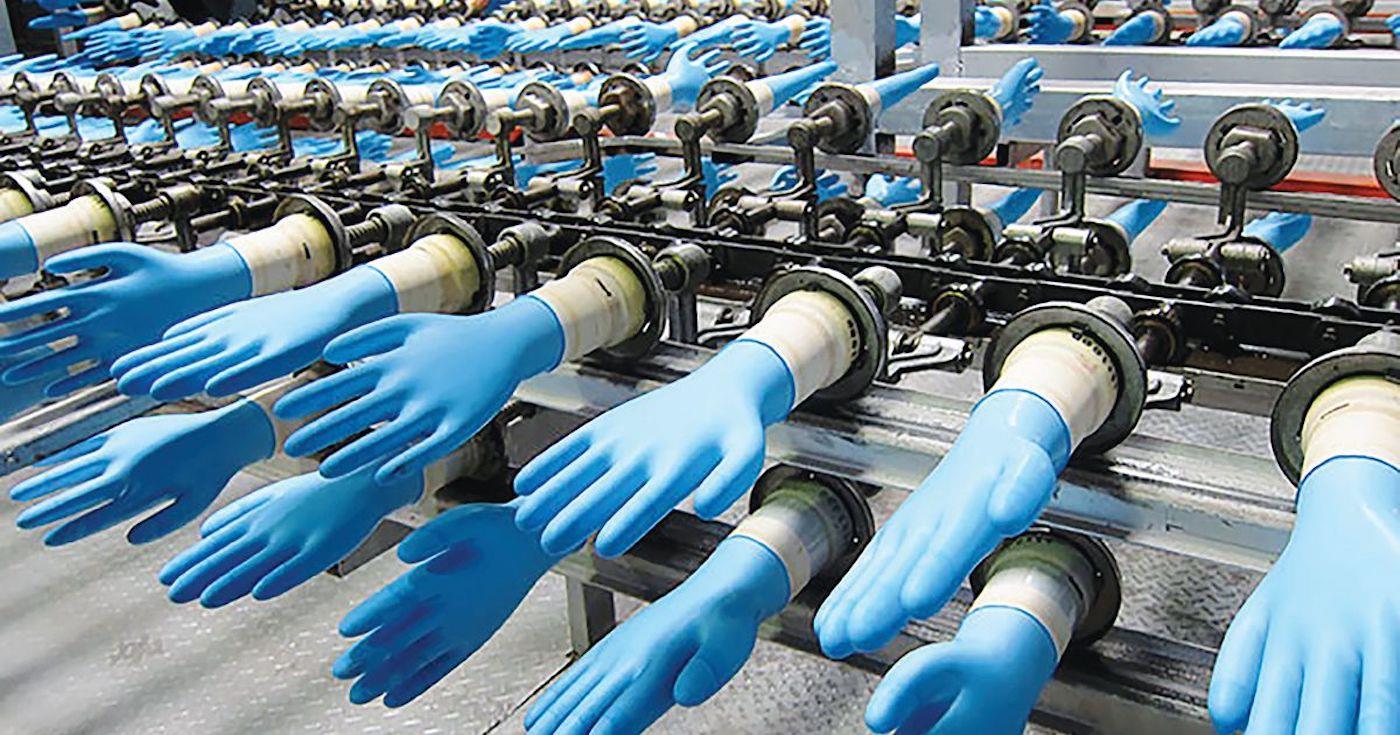

A rubber glove factory in Malaysia. The industry has come under rising scrutiny for labor abuses. Photo: Agencies

The CPB said it had identified seven of the ILO's 11 indicators of forced labor during a probe into YTY Group, including intimidation and threats, debt bondage, abusive working and living conditions, and excessive overtime following an initial complaint by Nepal-based independent migrant worker rights activist and researcher Andy Hall.

“I felt that there were a lot of indicators of forced labor, but I made YTY aware of that complaint very early on,” said Hall, who told Asia Times that he initially reported the glove maker to US authorities in 2020 after hearing workers' accounts of poor housing conditions, violations of accommodation regulations and unlawful recruitment practices.

YTY began to make improvements after being notified of his complaint and because other companies were being sanctioned, said Hall, adding that while the company had failed to be“completely transparent” during audits,“it was clear that they were making progress, so I was quite surprised to hear about the sanctions.”

Ravi Ragunathan, vice president of human resources at YTY Group, told Asia Times that the firm had voluntarily engaged with the CBP since mid-2021 to submit information on its social compliance policies, procedures, and achievements, adding that“impressive progress had been made in multiple areas of relevance” since early 2019.

“At no point did the CBP indicate to us that an active investigation was underway, nor what allegations may have been levied against us,” said Ragunathan.“Despite leaving multiple channels of communication open to them, at no point did the CBP reach out to seek clarification, request additional information, or generally engage with us.”

YTY Group began initiating payments to its foreign staff in October 2020 for fees charged to them by employment agents during their recruitment. Labor activists say recruitment fees into Malaysia are some of the highest in the world, partly driven by deceptive recruiters who in some cases charge more than a year's pay for job placements.

Remuneration payments by YTY Group were initially slated to be rolled out over 24 months, but the company expedited the pay-outs to conclude the process by June 2021, a decision it said was made primarily on humanitarian grounds after taking into account the impact Covid-19 has had on the families of its employees.

Ragunathan added that the firm remains“unaware of what information the CBP used to arrive at their conclusions, or in what manner that information was vetted to ensure it is timely, accurate and reflective of current conditions at YTY,” and is engaging with US legal counsel and other relevant stakeholders to address the CBP's allegations.

YTY Group told Asia Times that the WRO has caused“significant disruption” to its US customers at a time when the US Food & Drug Administration (FDA) has noted medical glove shortages in the US. The firm said it is the primary and, in some cases, the only supplier to numerous large and medium-sized US healthcare distributors.

An industry source who requested anonymity told Asia Times that the US market accounted for an estimated 50% of YTY Group's total sales volume. YTY Group declined to provide a figure but said the US was“a strategically important market” and that the firm is in the process of realigning its sales strategy to focus on alternative markets.

When asked what steps YTY Group would take to overturn the US import ban, Ragunathan said that the company“maintains that we are in compliance with all ILO forced labor indicators and will seek to demonstrate this to the CBP as expediently as possible, recognizing that additional audits may be required to substantiate our position.”

A production line at Malaysia's Top Glove Corp. Photo: Top Glove Corp

Only two Malaysia glove makers – Top Glove Corp and WRP Asia Pacific – have had US import bans on their goods lifted. In both instances, the companies pledged remediation payments to their employees and the CPB deemed their goods admissible for entry into the US after concluding all indicators of forced labor had been addressed.

“The CPB has developed a very forensic standard for lifting the WROs,” said activist Hall.“Independent respectable third-party actors, whether it be auditors or investigators have to come in to look at the 11 indicators of forced labor. YTY will have to prove that they have basically solved every single one of these 11 indicators, then the WRO will lift.”

Conditions such as threats of penalty, excessive overtime hours, unpaid wages, lack of rest days and unhygienic dormitories are among some of the indicators of forced labor as defined by the ILO, a specialized agency of the United Nations.“It's quite a lengthy process. But based on my understanding I think YTY will get off the sanctions in record time,” said Hall.

While US import bans have led to an estimated US$150 million in recruitment fees being paid back to workers across Malaysia's glove industry, according to Hall, bureaucratic failings and the CPB's incapacity to verify claims through in-person interviews have often meant that“sanctions are usually imposed when companies have actually started to improve.”

The CPB's import bans are“meant to protect US companies against unfair competition from overseas companies who are importing things into the US at a lower price because of the forced labor. It's not intended to protect workers,” said Hall, who nonetheless argues that punitive US actions have spurred positive change for migrant workers.

“We see increasingly the companies that are subject to these WROs really improving and workers getting a lot of benefits. Fees have been paid back to workers because of CPB pressure, because of the fear that companies are going to be sanctioned,” Hall told Asia Times.“Malaysia has been the poster child, the real success story for CPB.”

While critics of the CPB's actions in Malaysia typically acknowledge the realities of poor working conditions for migrant workers, many are still skeptical of broad claims of slavery in factories and plantations, and tend to see import bans as a means of introducing non-tariff trade barriers to restrict imports from developing countries.

But authorities in Malaysia have recently been more forthright in recognizing the problem than in the past. After visiting a glove factory in 2020, Human Resources Minister Saravanan Murugan admitted some companies engaged in“modern slavery” and said living conditions for workers in British-owned plantations during colonial rule were better than today.

Saravanan told parliament in November that forced labor issues had damaged foreign investors' confidence in the country as a reputable supply hub and in the same month launched a National Action Plan on Forced Labor (NAPFL), which proposes non-binding measures aimed at improving law enforcement and enhance related laws.

Under the framework, recruitment practices will be strengthened and victims of forced labor will be provided with improved access to remedy, support and protective services. The ILO, which worked with Malaysian authorities to draw up the action plan, described the undertaking as“a major step towards eliminating forced labor” in the country.

The NAPFL was unveiled only months after Malaysia was downgraded in the US State Department's annual“Trafficking in Persons” report last July to its Tier 3 category reserved for the worst country-offenders including Myanmar, China and North Korea. The report cited the Covid-19 pandemic as contributing to a surge in labor trafficking.

Malaysia's government had failed to make“significant efforts” to meet minimum standards and did not adequately address or criminally pursue credible allegations of labor trafficking, the US State Department concluded. Tier 3 countries could be subject to sanctions that restrict their access to US foreign aid or loans from multilateral banks.

A Malaysian rubber glove factory production line. The industry is under rising global scrutiny for labor abuses. Image: Supplied

Saravanan conceded that forced labor continues to be a major problem for Malaysia but expressed willingness to work with the US and United Kingdom to address the problem in a statement on February 10, responding to an article written by American and British diplomats in Kuala Lumpur published in the local New Straits Times broadsheet.

Charles Hay, the British high commissioner to Malaysia, and Brian McFeeters, the US ambassador to Malaysia, called in their February 9 article for bolder action, including holding perpetrators criminally accountable.“Addressing and preventing forced labor isn't just a human rights issue, it's an economic issue,” the diplomats wrote.

Analysts say the spate of US import bans on leading Malaysian companies has cast a dim light on successive governments' inability to prevent such abuses and undermined the country's reputation as a global production base, with some warning that future foreign direct investment and supply contracts could be affected.

“More and more, mid-market private equity firms are adopting ESG policies which attract capital from investors who require the same focus on sustainability from all funds in which they invest,” said Steven Okun, chief executive officer at APAC Advisors, an ESG consultancy based in Singapore working primarily with mid-market private equity firms.

“In Malaysia, forced labor will be a material ESG factor for any company that sources goods from there. Foreign investors continue to invest directly in Malaysia, or to source from Malaysian companies, but more and more will only do so after conducting serious due diligence on the employment practices in their supply chain,” Okun added.

It remains to be seen whether US pressure leads to meaningful reform and increased enforcement of labor standards in Malaysia. Labor activists have criticized the government's NAPFL for proposing non-binding remedies and for failing to address structural practices that enable abuse, such as migrants being tied to a specific employer through work permits.

Political observers also have doubts about whether the government can maintain a sustained focus on labor reforms given that priorities may shift following a change of government. Malaysia has had two governments fall to political defections over the last two years, triggering political instability that has stalled momentum for certain reforms.

“While signs are hopeful the authorities are taking these issues more seriously, if an investor has an ESG policy with a commitment to mitigate the harm from material factors, [investee companies] are responsible for meeting the promise to their investors, regardless of progress being made by the government,” Okun told Asia Times.

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment