Indonesian female school heads: why so few and why we need more?

(MENAFN- The Conversation) This article is part of a series to commemorate Indonesian National Education Day on May 2.

Women make up the majority of primary school teachers in Indonesia. Out of a total of 1,433,794 primary school teachers, almost 1 million of them are women – a proportion of nearly 70%.

But only a third of primary schools in Indonesia have women as principals. At Islamic schools (madrasah), the number is even lower; less than 20% of principals are women .

These gaps not only indicate gender inequality but also that many schools, in the world's most populous country, are not benefiting from the effective leadership of women principals and the better learning environments they tend to create .

We are part of Innovation for Indonesia's School Children ( INOVASI ), a partnership program between the governments of Australia and Indonesia that aims to improve students' learning outcomes.

In 2018, INOVASI conducted school surveys in 16 districts and one municipality in West Nusa Tenggara, East Nusa Tenggara, North Kalimantan and East Java. We surveyed 567 teachers and 199 school principals and analysed associations between variables.

Among other findings , the survey found that, on average, female teachers perform better in the classroom, and schools with women principals tend to have better school management and a more supportive learning environment.

But we also found female teachers have to wait longer to be promoted.

Read more: Research finds gender bias in textbooks of Indonesia and other Muslim majority countries

In some aspects, women perform better than their male colleagues …

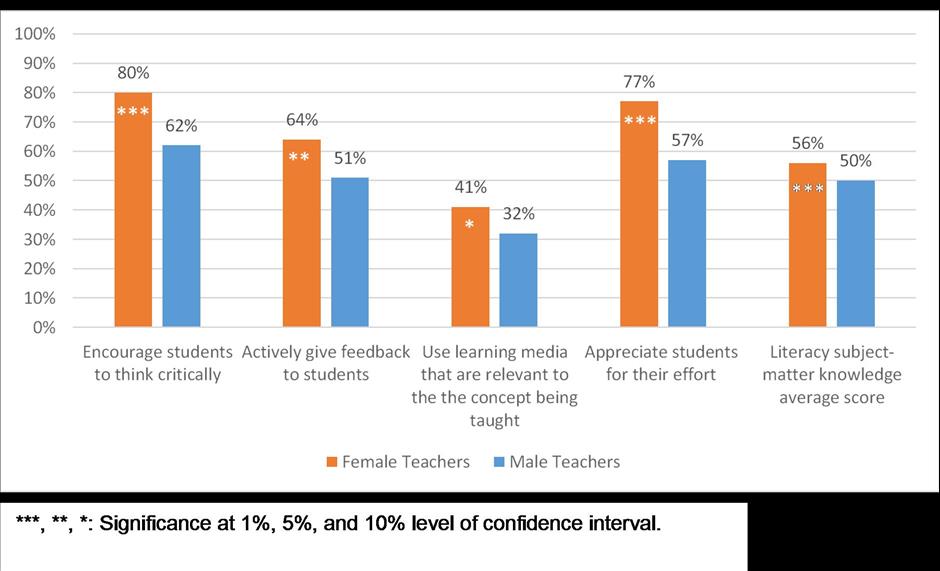

Teachers' performance and average literacy scores by gender. INOVASI, Author provided (No reuse)

We found women teachers were typically more appreciative of their students' work and more proactive in using learning tools (e.g. flashcards, big book, and cubes). A related study revealed that, compared to their male colleagues, female teachers spent more time actually teaching their students.

Female teachers also tend to achieve higher scores in the literacy test – although this is a preliminary finding.

We also found female principals tend to perform better in certain aspects of managing schools.

For example, we observed that female principals tend to allocate more funding for teacher development, student learning activities, and library management. On the other hand, male principals allocate more to teachers' salaries, multimedia tools and other operational expenses.

This may explain our other finding that more teachers were satisfied with the leadership performance at schools with female principals (84%) than at those with male principals (74%).

The academic literature suggests women tend to use more effective instructional leadership practices, which can have a positive effect on student learning outcomes.

Female educators are generally more effective in defining the school mission, organising the instructional program and establishing supportive relationships with staff and students. Female principals are also more likely to adopt a democratic, participatory and task-focused leadership style.

Another study finds that gender is linked with the principals' source of authority. Female principals are likely to rely on their instructional knowledge and experience, while male principals are more likely to trust their own decision-making ability and use their hierarchical authority.

Read more: Poor Indonesian families are more likely to send their daughters to cheap Islamic schools

…but they get slower promotionWe found significant gaps between the numbers of men and women principals in both regular primary schools and madrasah. At regular primary schools, only 30% of the principals were women; at madrasah, the number falls to only about 13%.

Despite their high performance, female teachers tend to be promoted to the position of school principal later in their careers. When promoted, female educators also have higher education levels and more teaching experience than their male counterparts. This supports findings that suggest women have to work harder for promotion.

A study in 2006 found that in several developing countries, including Turkey, China and some predominantly Muslim countries, latent discrimination against women resulted in women opting out of professional advancement.

These societies perceived leadership positions as 'belonging' to men and discouraged women from attempting to achieve such positions.

In Indonesia, history shapes gender roles. In the New Order period, gender relations and roles were strongly controlled by the state, defining women as mothers and wives and confining them within the domestic sphere .

This politics of gender resulted in discriminatory social constructions of gender roles. When women participated in development, it was merely to help the men , and when women worked it was not considered ' real work '.

Another aspect to the issue of female educators is that school principals have a heavy workload and this creates further challenges, particularly for married women.

One woman principal we interviewed said she spends long hours on supervision and administrative work. This work also requires her to be mobile and prepared to visit remote areas – a requirement generally considered more suitably fulfilled by men. Principals also need to be prepared to be posted anywhere.

These challenges make it likely that women, especially married women, will find it difficult to pursue leadership positions in the education sector.

Women tend to face conflicting demands from their professional roles and their family responsibilities. It's a common experience everywhere but particularly in developing countries.

Read more: Lack of internet access in Southeast Asia poses challenges for students to study online amid COVID-19 pandemic

What can we do?While available literature on gender disparities in leadership in the education sector in Indonesia is still limited, we can take some steps to improve the situation.

In the short term, we can begin by tackling women's practical gender needs and gradually build the foundation for more progressive efforts to eliminate inequities.

An example of this is to provide specific leadership training to empower women teachers. Women might face more challenges to pursue their career such as having to overcome internalised patriarchy that stops them from pursuing leadership positions. They also may need to navigate domestic responsibilities and leadership demands.

Current leadership training in education is largely gender-neutral and does not address these woman-specific needs. Leadership training may need to cover more women-only sessions that include topics like mentoring, rebalancing domestic roles and developing leadership qualities.

Current leadership training for principals can also be adjusted to incorporate gender-related topics and encourage all participants, both men and women, to learn from positive examples of female principals.

In the long run, a better understanding of how gender differences shape school performance will be valuable input for the government, particularly in filling school leadership positions.

While affirmative action may be required as part of the intermediate solution, the ultimate aim is to ensure leadership roles are filled based on candidates' qualities and competence.

Better school leadership means better school management, better teaching and better learning outcomes for Indonesian children.

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment