(MENAFN- ING) How can

The Netherlands build on its technological capabilities to lead the green transition? And to succeed, what are the economic choices we're all going to

have to make? ING's Chief

Economist, Marieke Blom, has some answers in this speech to students at the University of Eindhoven In this article The transition is cheaper than climate change We will need radical interventions in the market to save our plSupport for implementing concrete interventions will be a very important hurdle The production side of the Dutch economy is very capable of changing The worker angle The consumer side Politicians have to consider economically inefficient subsidies to turbocharge the transition

ING's Chief Economist, Marieke Blom We are at the start of the academic year, and any start deserves a motivational speech. What motivates you to get going? Is it fear? Or is it confidence? I would say most people need a blend, but confidence is an essential ingredient, and that will be my focus.

The question I was asked to answer:“If The Netherlands wants to lead the green transition, building on its technological capabilities, is this economically viable?".

So, we need to look at the costs any disruption will entail. And my short answer is this: I am confident the Dutch economy is well capable of dealing with the transition.

We are way beyond the planetary boundaries. We are so far beyond them that it comes at a price that will only increase in the future. Many economic estimates show that the costs of avoiding climate change will be lower, possibly significantly lower, than the cost of climate change itself.

To assess all this, I'm going to examine some personal convictions.

The transition is cheaper than climate change I am convinced that we have a positive economic business case for greening our economy.

Here's a fun fact: Eurobarometer shows an astounding 73% of Europeans agree with this [that the cost of the damage caused by climate change is much higher than the cost of investing in a green transition].

How to do it? Do we go for de-growth or for green growth? Speaking here in Eindhoven, of course, we all agree there is a lot technology can do. Look at the speed at which the costs of solar and wind power came down or the adoption of working from home. There is a lot to say for the tech-optimists who say we can and must rely on green growth, technology and human ingenuity can do incredible things. But just relying on technology is naïve. It does not take into account how markets work.

Firstly, technologies such as solar and wind were speeded up by government interventions. Secondly, every invention of cheaper technology will also induce additional demand. Look at energy-efficient LED lights: an energy-efficient alternative to light bulbs, but now entire buildings are being lit up.

Economists call it the 'Jevons paradox' or rebound effects. Hence, the need for conviction number 2.

We will need radical interventions in the market to save our plWhile these interventions are in the overall best interest, they will create winners and losers. How to go about this?

Team 'green growth' will say: Let's just make sure we organise sufficient growth, as that will help compensate losers and that way, green policies will get public support.

Sounds attractive, but this is where I have changed my mind.

Neither growth nor affluence are sufficient to get support for interventions. This is clearly visible in, for example, in the ban on combustion engines here in Europe, the ESG backlash in the US, or the nitrogen policies here in The Netherlands. Even in a rich country such as The Netherlands, people support climate policy in general, but a majority fear the effect on their cost of living and energy bills.

Psychology offers help in explaining what happens when countries get richer. Firstly, there is a thing called staquo bias – people don't like change. Also, a loss is a loss, even if it is a relative loss – the Easterlin paradox. Thirdly, the loss is often concentrated amongst a small group of workers and corporates. Think of a factory closing – the workers and owners are very aware of what they lose, and they may lose a lot. Winners will not realise they live longer or get a new job because of that factory closing down.

So economists, myself included, have been naïve in saying 'just promote growth while giving the right incentives'.

Support for implementing concrete interventions will be a very important hurdle And that conviction is true even in affluent societies, so economists must also think about it. There are two lenses on economic impact: the impact producers - employees, corporates, capital – and consumers.

Let's first look at the producer side and what would drive support for change. Corporates and labour unions alike will point to the risks of the transition for existing industries and their workers. This is a forceful lobby, and like with the ban on combustion engines, it leads to delays. I would encourage politicians to be confident here.

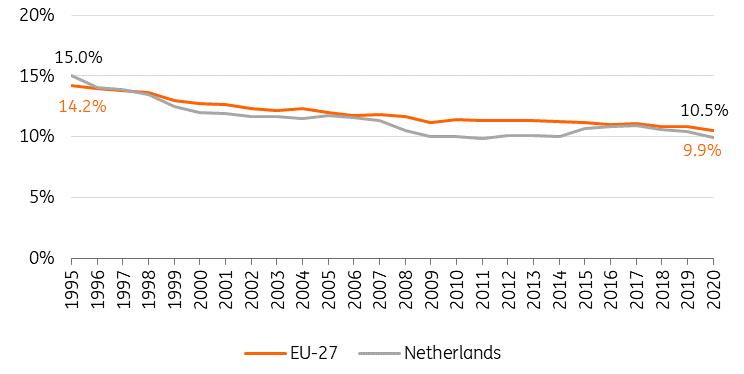

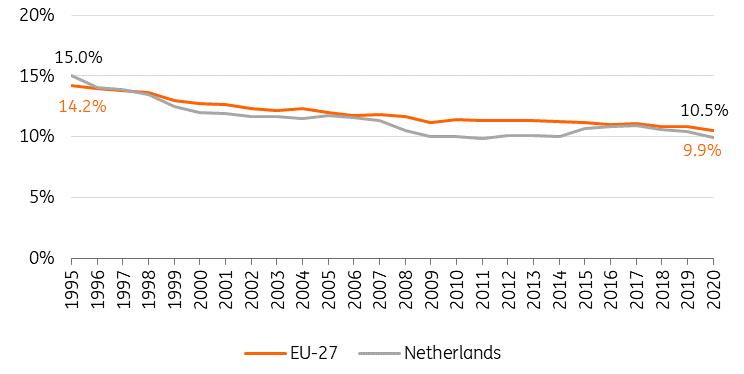

The production side of the Dutch economy is very capable of changing So, let's look at the conviction from the corporate angle: corporates will have to adjust to new technologies, but we've seen that before, like with the adoption of digitisation. Helped by great digital infrastructure, Dutch corporates were ahead of most of Europe. Industries will lose, but we've seen that before with textiles, coal mines and shipping. Also, the share in GDP of the most energy-intensive industries, such as agriculture, food, chemicals and transport, declined from 15% to 10% in the Netherlands from 1995 to 2020.

That is faster than the European average, but economic growth here was higher: 63% ver51% on average. Why? We benefitted from structural strengths like infrastructure, educational levels and institutions. This is what politicians should invest in.

Value-added share of GDP (=all NACE activities) of most energy intensive sectors* Current prices

Eurostat, ING Research

*Agriculture, Food industry, Petrochemical, Power sector, Chemical industry (=estimate), Building materials, Basic metals, Land transport, Shipping & Aviation The worker angle The Dutch labour market is very flexible. Labour market transitions are frequent; a large share of the population is employed on flexible contracts, and this flexibility has increased over time. Looking forward, with increased possibilities for working from home, regional differences in unemployment are easier to absorb. Also, labour markets are tight and expected to remain so because of ageing.

Employees will have to be retrained, but we have done that before: the share of those less educated in the workforce fell from 60 to 20 percent in fifty years (link to research in Dutch here ). And these days, we can learn and teach via digital tools.

Lastly, green solutions are often quite labour-intensive. So, while in previtransitions unemployment was a big issue (for instance, when the coal mines closed), it should be much less of a concern now.

Despite all this, politicians may be inclined to foon protecting the energy-intensive industries we currently have by giving high transition subsidies for fear of losing what we have. And it's true that existing industries are part of our comparative economic strengths. Economists call that path dependency. But that should not lead to tunnel vision, where the discussion is left to dominant, prevailing industries.

Simply protecting what we have today belies a lack of imagination about what may come tomorrow. Thirty years ago, Dutch politicians would not have dared to dream about the strength of ASML and the Eindhoven region today. The Dutch government must provide the economic infrastructure to enable Dutch corporates and workers to deal with change.

The consumer side Let's look at the consumer side of the economy next. The Dutch public generally agrees that things need to change, but there is a widespread fear it will come at a high price, especially for lower-income households. I believe this risk for lower incomes is much smaller than people think.

Firstly, because people forget the positives. Secondly, people need to realise there are ample possibilities to mitigate adverse income effects. Take these positives as an example:

EVs will have a lower total cost of ownership than combustion engine cars. Led lights are cheaper than traditional light bulbs. Solar power will limit the electricity bill.

There will be economic gains, too. The mitigation of income effects: Currently, the heating bill is relatively costly for lower incomes. So, once homes are insulated, lower-income households may benefit. In The Netherlands, they mostly live in rental homes. So, if the government introduces a norm where energy-inefficient homes cannot be rented out from a certain date, lower incomes will benefit.

For homeowners, subsidies can help make insulation a financial win. It does require a decent level of subsidisation, which is easy to make use of, but this can certainly be designed. Embracing subsidies is new for me. I used to be one of the economists who strongly preferred efficient incentives like carbon pricing, as subsidies will have to be paid for by higher taxes. However, there's research (here, FT paywall ) that shows price increases such as emission taxes damage support for the transition more than norms like emission limits and subsidies.

Politicians have to consider economically inefficient subsidies to turbocharge the transition And this is my fifth and final conviction: The green transition overall is economically beneficial. Governments must intervene strongly in markets. Support for interventions is a significant hurdle. Corporations and workers can deal with change if governments ensure high-quality institutions. The transition can be made digestible for consumers, where necessary, with subsidies.

So, from an economic perspective, I am convinced The Netherlands can and should embrace the transition.

Please help me to share that confidence in society. Meanwhile, to you as engineers of the future: My confidence is based on trust in your capabilities to develop cleaner and more energy-efficient technologies. Please get that going as fast as you can.

Comments

No comment