403

Sorry!!

Error! We're sorry, but the page you were looking for doesn't exist.

Italy and North Africa in the 21st Century

(MENAFN- Morocco World News) Italy as a nation and as a civilisation has always been present in the life destiny and imagination of North Africa and will always be for a long time to come vivid and omnipresent. For the South Mediterranean people Italy is more than a country and a culture it is a sort of an icon. Many times when lay people are asked about Italy they would say without thinking 'they are very much like us' meaning: They look like us physically;

They think like us;

They feel like us;

They act like us; and

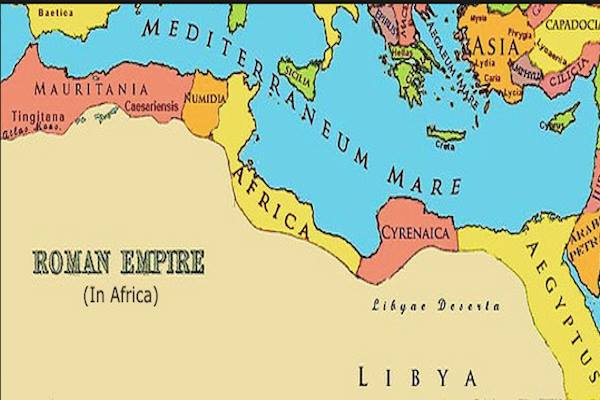

They react like us. In short the North Africans see the Italians more like Mediterraneans and certainly not like Europeans: the common denominator being the Mediterranean identity and the Mediterranean culture which is the groundwork of a tacit understanding irrespective of creed and social level. Do the North Africans feel the same for the Spaniards and Spain where the Arab culture thrived from the time of its conquest by the Berber general Tariq Ibn Zayad in 711-718 to the advent of the Reconquista and the fall of Grenada in 1492? Both Spain and the rest of Europe were in the past seen as dar al-kufr as opposed to dar al-Islam. As for Italy it is seen and has always been seen in good light: humanistic and friendly open and respectful. However one wonders if this is due to a shared past or to the common present or to the hopeful future? Shared past: the Roman Empire (27 BC-476 AD) When the Roman Empire extended its axis romanus to Africa it occupied a coastal stretch extending from Morocco all the way to Egypt and divided this large expanse of diverse land into regions bearing the following names: Mauritania (Northern Morocco and Algeria) Numidia (Eastern Algeria) Africa (Tunisia) Cyrenaica (Libya) and Aegyptus (Egypt). Roman Empire in North Africa

They latinised this part of the world and imprints of this are still present today in the Amazigh language in its different dialects: Latin words in Tarifit dialect: Pirus firas 'pear' Filum firu 'thread' Asinus asnus 'donkey' Hortus orthan 'orchard' Pullus fullus 'chick' and in Arabic language too: Latin words in Arabic language: Cuppa qubba 'dome' Scapha saqf 'ceiling' Tellus till 'hill' Sigillum sijil 'seal' In the administration of the territories of North Africa the Romans were extremely flexible in their approach they allowed the indigenous people to hold important positions in the administration and in the army as indicated by E. Guernier:[1] “Un fait parait dominer toute l'administration romaine: une extreme souplesse dans l'application des mesures legislatives et des reglements. D'autre part une place importante est faite aux indigenes dans les rouages imperiaux aussi bien dans l'administration civile que dans les cadres militaires.” Economically speaking the Roman colonisation did not improve the living conditions and standards of the population that was in its majority made of peasants and nomads. Already under Carthaginian rule the North Africans were used to the techniques of the cultivation of wheat barley vines and olive trees which are still somewhat the basic crops of the area today. However the most remarkable achievement of the Romans in the region is undoubtedly the introduction of sophisticated irrigation systems and techniques.[2] They built aqueducts for the cities cisterns for the farms and artesian wells for the oases. The most well-known irrigation works the Romans left behind are: the aqueduct of Carthage and that of Cherchell the dam of Kasserine and the cisterns of Cirta and Hippone. The Romans also taught the locals techniques to collect rain water in valleys in order to use for agriculture when needed and to build irrigation ditches along rivers and streams to use the water for the neighbouring lands. It is also a known fact that the Roman legion had in its ranks many engineers who provided advice and also built underground canals like the one in Bougie Algeria. It is thanks to the experience of the Romans that Berbers developed their own techniques in irrigation such as the famous khettara-s in the plain of Marrakech and the water towers that organise the distribution of water along the two sides of the Atlas chain of mountains. The Romans also built several roads to secure the control of the territories and allow the exchange of goods between the people. Some of the known roads of the time are: -the Carthage-Thevest road 275 km long; -the Carthage-Tripoli road 823 km long. These roads necessitated a good knowledge of bridge-building over rivers and streams and wadi-s. Among the other Roman influences still present with the population of North Africa is a certain obsession with cleanliness. Indeed the Romans built baths everywhere and encouraged people to bathe frequently and they made out of them public places of intellectual discussion and commercial transactions and political lobbying. The Romans also washed excessively before between and after meals. Indeed slaves passed between the beds on which lie their masters and guests and poured on their fingers fresh perfumed water.[3] Later on when the Muslims arrived they had no problem as they did in some other areas in introducing the concept of cleanliness and the idea of ablutions before prayer. Today it is a common practice in North Africa to offer guests on arrival to freshen up and also to wash before and after meals. Among the celebrations and the rituals still common in North Africa and especially in Morocco there is the Boujloudia known in Berber as bou-ihidorn bou-ilmawen or bou-isrikhen[4] that often takes place during the religious celebration of l-aid l-kbir 'the feast of sacrifice'. On the first day of the feast a ram is ritually slaughtered in remembrance of God's request made to Abraham in a dream to sacrifice his son Ismael to him. In fact this practice is quite common in many areas in Morocco and in some parts of Algeria and Tunisia and its existence is traced back to ancient Greece and ancient Rome. It used to take place in the summer at the end of the agricultural cycle when the crops have been reaped as gesture of thanksgiving to the gods for their generosity and a prayer for more fertility for the coming year. However in the Jbala region of north-western Morocco in the village of Tatoft among Ahl Srif an arabised Berber clan there is a professional group of musicians known as the Master Musicians of Jahjouka who have given the rites of Bou Jelloud a special significance because they believe that their rites hark back to pre-Islamic times and derive from the rites of Pan.[5] Their origins stem from Greek and Roman influences and correspond – in the wild chase of Bou Jelloud (the father of skins) the instigator of a fertility dance – to various fertility traditions found in most Mediterranean countries. There is even a reference to this tradition in Shakespeare's Julius Caesar (Act1 Scene 2): Forget not In your haste Antonuis To touch Calpurnia For our elders say The barren touched in the holy chase Shake off their sterile curse Even today the ceremony still involves Bou Jelloud emerging from his place of concealment on hearing the sounds of ghaita-s[6] and dancing himself into a trance while flailing women with branches to make them fertile. The location of these rites is a small village situated in the Jbala region of Northern Morocco in the piedmont area leading further east into the mountains of the Rif. The village of Jahjouka is still the home of Pan the goat like god and his persisting presence is a challenge to time space and religion. The tradition emerged from Egypt and despite transformations of nomenclature and culture it has been transmogrified into the practices of the Master Musicians and their practice of the Pipes of Pan. A crucial factor in this development was the fact that the introduction of Islam in the Jbala region did not destroy the pre-existing traditions. Islam was introduced in 800 AD by the eastern mystic Sidi Ahmed Sheikh who allowed local practice to continue unhindered and even managed to dignify it by granting it baraka.[7] The musicians involved were therefore able to depend on their music to earn their living. Today the musicians receive a tithe – ziyara – from local people for their music and it is this on which they survive. In return they play ghaita music in the courtyard of Sidi Ahmed Sheikh's shrine which is located in the village of Jahjouka. Visitors come to the shrine – kubba – every Friday to seek baraka from the saint. The musicians also fulfil a psycho-medical function for they cure the sick and those with medical disorders. Those afflicted are tied to a tree in the courtyard of the shrine and the ghaita and tbel [8] are played by the musicians to drive out the demons supposed to be responsible for the illness- whether physical or mental. Joujouka Masters Musicians The Healing Power of a 4000 year old Music. (Photo Courtesy of querrillazoo.com)

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment