(MENAFN- Asia Times)

China's Economy is having major problems. Despite the country's dominance of global manufacturing, its living standards are starting to stagnate at a level far below that of developed countries.

China's growth has slowed down dramatically, from around 6.5% before the pandemic to 4.6% now, and there are credible signs that even that number is seriously overstated . See this , this , this and this on the theme. I think everyone cited here is broadly in agreement.

But in the background, China has another problem that's weighing on its people's prosperity and also making it harder to respond to the macroeconomic crisis. This is the problem of chronically low productivity growth.

I don't quite believe the official numbers that say China's total factor productivity (TFP) has fallen over the past decade and a half, but it's undeniable that it has grown much more slowly than in previous periods.

Why? Paul Krugman points to a sectoral shift toward real estate - an industry with slow productivity growth - after the global financial crisis of 2008. I think that's definitely a part of the story, but probably not all of it.

Back in 2022, I wrote a post thinking through various possible reasons why China's productivity growth declined long before it reached rich-world living standards .

So in light of China's current struggles, which have only gotten worse in the intervening 2.5 years, I thought it might be helpful to repost it now. I think what I wrote holds up pretty well.

It's always an interesting experience to read books about China's economy from before 2018 or so. So many world-shaking events have changed the story since then - Trump's trade war, Covid, Xi's industrial crackdowns, the real estate bust, lockdowns, Russia's invasion of Ukraine. Reading predictions of China's evolution from before these events occurred is a little like reading sci-fi from 1962.

When I started China's Economy: What Everyone Needs to Know® , by the veteran economic consultant Arthur Kroeber, I was prepared for this surreal effect. After all, it was published in April 2016 - not the most opportune timing. So I was pleasantly surprised by how relevant the book still felt.

Most of the book's explanations of aspects of the Chinese economy - fiscal federalism, urbanization and real estate construction, corruption, Chinese firms' position within the supply chain, etc. - are either still highly relevant, or provide important explanations of what Xi's policies were reacting against. Dan Wang was not wrong to recommend that I read it.

But China's Economy is still a book from 2016, and through it all runs a strain of stubborn optimism that seems a lot less justifiable six years later.

Most crucially, while Kroeber acknowledged many of China's economic challenges - an unsustainable pace of real estate construction, low efficiency of capital, an imbalance between investment and consumption, and so on - he argued that China would eventually overcome these challenges by shifting from an extensive growth model based on resource mobilization to one based on greater efficiency and productivity improvements.

This was despite his acknowledgement of the fact that productivity growth had already slowed well before 2016, and that Xi's policies so far didn't seem up to the challenge of reviving it.

In many ways, productivity growth is the thread that ties together the entire story of the Chinese economy since 2008. Basic economic theory says that eventually the growth benefits of capital accumulation hit a wall, and you have to improve technology and/or efficiency to keep growth going.

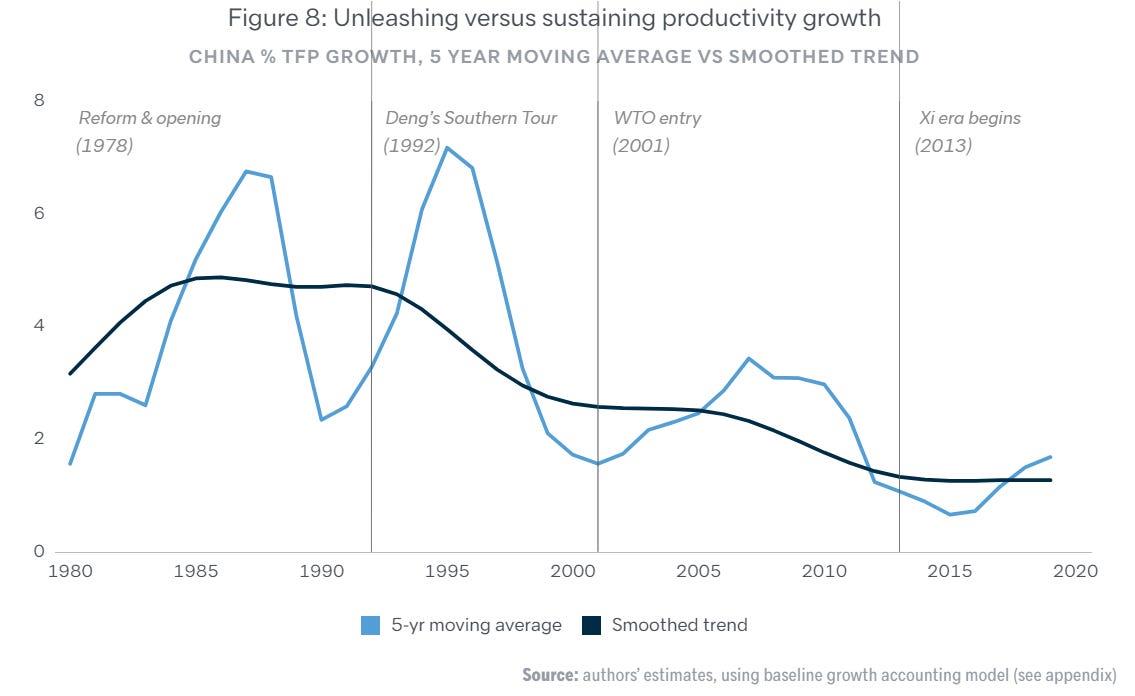

Some countries, like Japan, South Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan, have done this successfully and are now rich; others, like Thailand, failed to do it and are now languishing at the middle-income level. For several decades, Chinese productivity growth looked like Japan's or Korea's did. But slightly before Xi came to power, it downshifted to look a bit more like Thailand. Here's a graph from a Lowy Institute report :

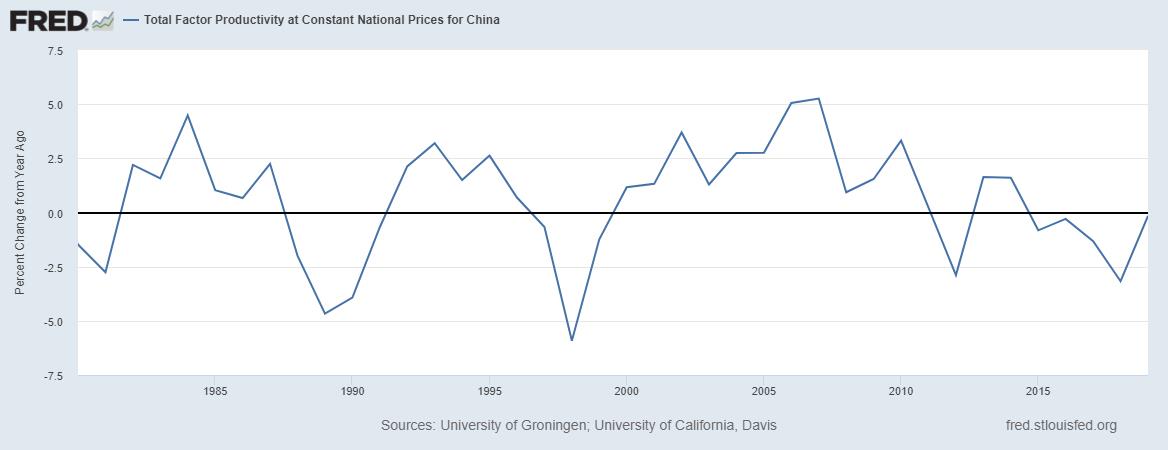

Source: Lowy Institute In fact, the Lowy Institute's numbers are more optimistic than some other sources. The Penn World Tables has China's total factor productivity growth at around 0 or negative since 2011:

And

the Conference Board agrees .

Personally, I suspect these sources probably

underestimate TFP growth

(for all countries, not just for China). But even Lowy's more reasonable numbers show a huge deceleration in the 2010s. If this productivity slump persists, it will be very difficult for China to grow itself out of its problems - such as its

giant mountain of debt

- in the next two decades.

The question then becomes: Why has Chinese productivity growth slowed to a crawl? There are several main candidate explanations, and they have important implications for whether Xi will turn things around.

The first reason, of course, is that China had several tailwinds that were helping them become more productive, and these are mostly gone now.

Reason 1: Hitting natural limits

One thing helping Chinese productivity growth was simply their distance from the technological frontier. When you don't even know how to do fairly simply industrial processes, it's pretty easy to learn these quickly.

China imported basic foreign technology by insisting that foreign companies set up local joint ventures when they invest in China, by sending students overseas to learn in rich countries, by reverse-engineering developed-country products, by acquiring foreign companies, etc. Also by industrial espionage, of course, but there are lots of above-board ways to absorb foreign technology too.

MENAFN30122024000159011032ID1109040388

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images, videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.