University Of Houston Students Lighting A Bright Path To The Future

In August 2023, the Baker Hughes Foundation awarded a $100,000 grant to the University of Houston Energy Transition Institute (ETI) to support environmental justice research and workforce development programs. The grant has multiple beneficiaries, including undergraduates in the university's Energy Scholars Program working on research around carbon management, hydrogen, and circular plastics. University of Houston's (UH) Energy Scholars program enhances the professional development of students by having them work with research faculty and industry partners on projects focusing on energy matters.

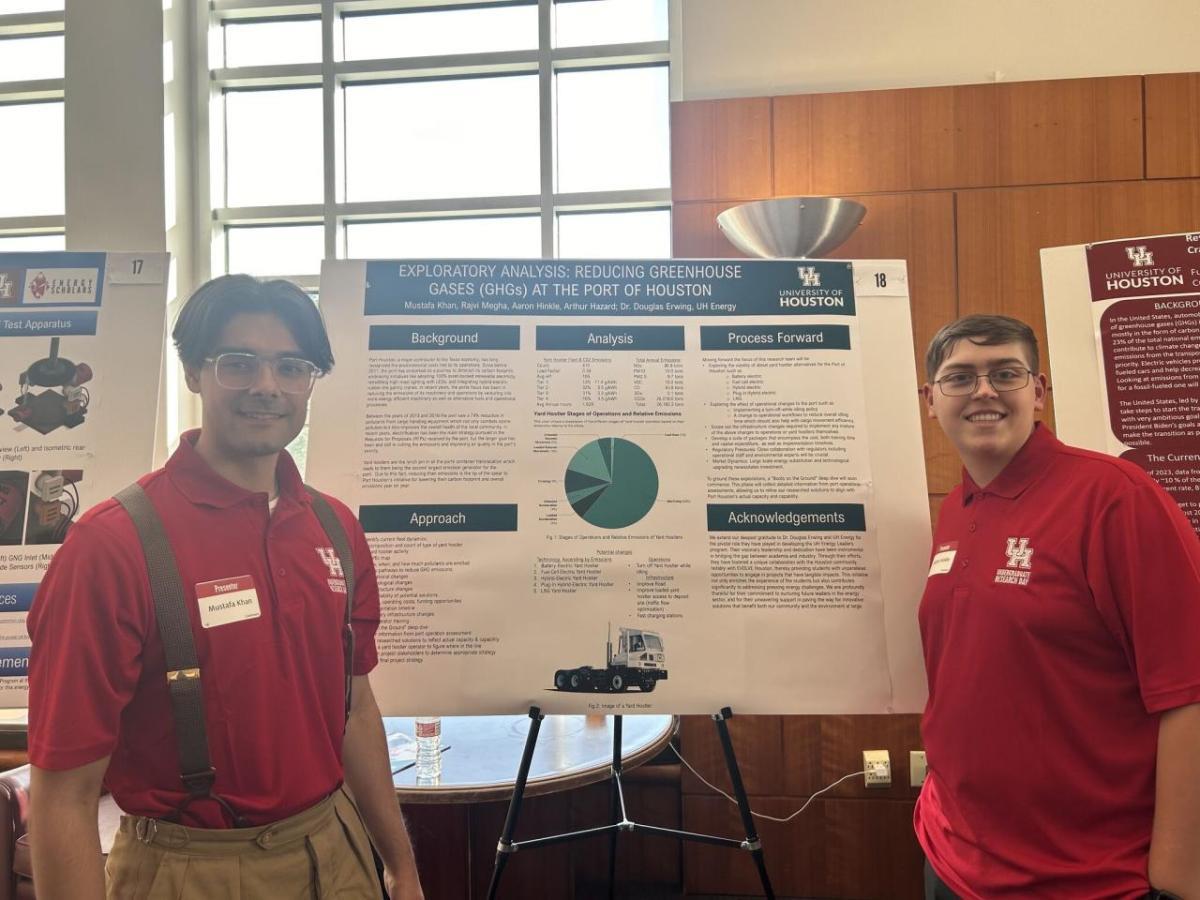

We sat down with two students from the program, Mustafa Khan and Aaron Hinkle, to hear about their research project, Exploratory Analysis: Reducing Greenhouse Gases (GHGs) at the Port of Houston.

QUESTION

Could you please each tell us a little about yourselves?

MUSTAFA KHAN:

I'm studying quantitative economics and have taken a diverse array of courses. I've had the pleasure of going pretty deep into the math and physics departments. Delving deeper into these multidisciplinary fields allows me to better understand the world around us today and to be a greater contributor to what we need to do to make tomorrow happen.

AARON HINKLE:

I am a sophomore honors mechanical engineer student specializing in robotics. In addition, I'm the president of the UH Robotics Club and I'm involved in the UH Energy Coalition.

QUESTION

What does the energy transition mean to you and how does that play into your everyday life?

KHAN:

When we think about the energy transition it's ordinarily around the adoption of new technologies and more efficient ways to produce energy. However, when we get into the details, the transition is multidisciplinary. It's about how we approach the environment, future work opportunities and public health.

As we think about what these new technologies look like, we're spending a lot of time thinking about each individual element involved in the whole process. We need to consider how we maximize the efficiency, the technologies, the conversations, and the communications to make these projects happen. We're connecting with our communities to understand people's needs – what do they want, what do they like, what would they prefer to have compared to what they have right now?

What we're looking at for the future is this massive collage of distinct specializations to approach new ways of handling everything that we do today, whether it's water resource conservation and development or utilizing solar radiation to generate power. Whatever it might be, it all translates into things that we do every single day. It all translates to how we live our life, and to hone in on these technologies and methodologies that are conducive to the world we want to make. A world that is sustainable and allows people to live the way they want to live. It requires just an incredible amount of specialization to do this.

As we make that shift to decarbonize, we will see that it makes a major difference to people's public health. The hope for me is that as we make progress, people will be able to work wherever they want in any city, along any coastline, and live a healthy life. You can come home to your family and smile – that's what the energy transition means to me.

HINKLE:

The energy transition for me means a brighter future for my family and the next generations. What I really care about is making the world a better place for everyone.

QUESTION

Could you tell us about the research project you've been working on together?

KHAN:

Aaron and I have been collaborating on an incredibly interesting project that ties into the energy transition in terms of reducing emissions around operations at the Port of Houston. We're in the early stages but we've made a ton of great progress and done a ton of great research. We've locked in on what are known as "yard hostlers," which are fundamental to cargo operations at the port. Yard hostlers are miniature trucks that take freight from one location to the next within the port, and they're diesel-powered. Because they're used in all container translocation, they're the second-largest emission generator for the port. We're working on ways to identify pathways to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions and the viability of potential solutions.

HINKLE:

The Port of Houston Authority sent out a Request for Proposals (RFP) and Evolve Houston , a non-profit organization working to decarbonize transportation in the city, brought it to us at UH. They let us know that the port was looking for research into how it could reduce GHGs specifically around introducing yard hostlers using different fuel. UH works very closely with Evolve Houston and it seemed like a great project for us to work on. We're looking at electric-battery, LNG-powered and hydrogen-fuel-cell powered yard hostlers. The next step is considering the infrastructure the port would need. For example, for LNG, you'd need LNG stored at the port and a way to get it there.

QUESTION

It's early days but what have the challenges been so far in the project?

KHAN:

One of the bigger things that we've really been battling to understand is the operations component of it. Engines at different RPM s consume different levels of fuel and therefore a different output of emissions. We can gather that data easily, but we need to dive into the why – why are the yard hostlers idling or creeping, which is traveling at less than 4 mph? How can we make this more efficient? We'd like Aaron and I to get down there with our feet on the ground with stopwatches to gather more information, but understandably there are issues around getting non-Port Authority people access. But we intend to ensure that we do have quality data that we collect ourselves, to give us insights that we can then use to bolster our ideas.

HINKLE:

We can look at different fuel sources, existing technology, leasing programs and an implementation timeline. These are all things that are within our scope. What is exciting is that our entire research team is talking about developing our own type of technology to meet the port's needs for the yard hostlers. The challenge is that the lead time of developing a new technology, testing it, getting the proper funding to build a prototype, would take this project timeline out to be years! We're trying to figure out the most effective approach and how far we go.

QUESTION

How have you found communicating with the actual operators at the port?

KHAN:

That has probably been the biggest hurdle to be honest. Operators don't always want to change their ways or learn about a new technology which could be more efficient. We're academics coming in with no experience in these operations trying to convince them to inform us about the decisions that they make when they're operating in a typical shift. We would like to find out why they choose to stall versus accelerate or choose to lock themselves in slower traffic as opposed to taking a more efficient route. This is information we so far have not been able to gather.

QUESTION

Are your mentors from the University of Houston able to help?

HINKLE:

Our mentor Doug Erwing has been working with us to keep us on track and advocating for us, getting us meetings with Evolve Houston and trying to help us organize the boots on the ground research going. He's been really helpful.

QUESTION

You talked about a multidisciplinary ecosystem needed to drive decarbonization.

How important do you think it is for companies from across different sectors, NGOs, and academics to collaborate to help drive the energy transition? Can they make a difference?

KHAN:

Giving the university the opportunity to collaborate across divisions and have these research opportunities for students to get engaged is great. It could be interesting to develop a survey course, which could be offered to specific majors, a college, or a whole-of-university initiative, where an interdisciplinary program would see the professors in constant collaboration with companies.

For example, they could work with specific divisions within Baker Hughes and the company could talk to the professor about what they're finding in their work and where they want it to go. Then that survey course becomes a conversation around that, with projects that directly tie into the necessary skills students need when they get out there and start looking for jobs. That kind of collaboration could be incredibly valuable. There's a big opportunity to build a pipeline of talent through collaboration of industry and universities – it's about identifying the best way to do that.

HINKLE:

I agree. If universities can work with companies to help train students and build pathways for them to get into specific lines of work after graduating – for me, I'm really interested in robotics. So, anything my university can do to help connect me with prospective employers in this field, will also mean that in turn I can share my knowledge from my studies with them.

QUESTION

What are you most excited about for the future?

HINKLE:

I'm looking forward to learning new things and setting up connections where people can teach me new things. I want to learn as much as possible because I love learning. I want to continue learning forever.

KHAN:

University students are all gluttons for learning. What really excites me is that as we go out there and as we start contributing and making an impact, the constant flurry of new learning will not be like anything we've seen before.

We have these real problems that are going to take real effort to solve and once we do solve them, the innovations and the opportunities that will be created and the new doors that will open will be so incredible. That's what I'm looking forward to.

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment