(MENAFN- Asia Times)

A winter of fear looms as Russian forces mass on the border with Ukraine, sending shivers down the spine of NATO. But the ongoing war of nerves over Donbass is a far cry from the desperation and slaughter of 80 years ago this December, when one of the most critical struggles in the greatest war in history played out before Moscow.

After blitzing across the USSR in the seismic Operation Barbarossa, Nazi forces were halted before the Soviet capital, then routed in a counter-offensive in December 1941. That intense drama marked the first real defeat of German land forces in World War II.

The events of eight decades ago marked a turning point in the fighting on the Russian front, the biggest and most murderous battlefront in the biggest and most murderous of wars.

The terrible milestones of that front – the reversal of fortune in front of Moscow; the hunger siege of Leningrad; the frozen slaughter ground of Stalingrad; the seismic armored clash at Kursk; the Red Army's vengeful pursuit of an increasingly desperate Wehrmacht during its scorched-earth retreat into Eastern Europe; the endgame in the ashes of Berlin – have been hammered into the annals of history.

However, all those milestones fall within the conventional borders of a historiography that has the German-Soviet war beginning with the Axis invasion of the USSR in June 1941 and concluding with the downfall of Nazi Germany in May 1945.

In fact, Stalin's war was not limited to the western Soviet Union – nor, indeed, to the struggle against Hitler. A new work, Stalinism at War: The Soviet Union in World War II by Mark Edele (Bloomsbury Academic, 2021) massively expands the frontages.

It is an expansion that takes place in terms of both space and time.

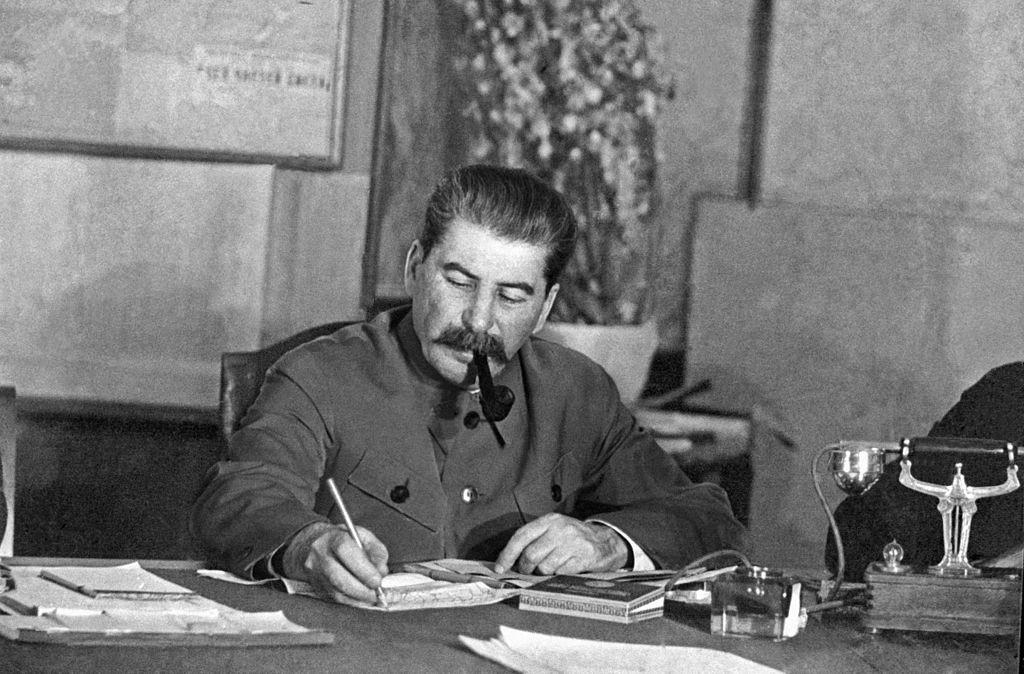

A new work finds that Josef Stalin was a master strategist – but does not question the ruthlessness of his dictatorship. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Broader, bigger, bloodier

Edele, a specialist in Josef Stalin and a professor at the University of Melbourne, kicks off Stalin's wars in 1937 with border skirmishes against the Japanese in the Far East, and only ends the blood-letting in 1949, when the last anti-Soviet nationalist partisans are eliminated in the Baltics, Belarus and Ukraine.

Between these landmarks, the book traverses the USSR's invasion of eastern Poland, the annexation of former Czarist territories in the Baltics, the Winter War with Finland, land grabs in Rumania, the gargantuan death struggle with Nazism, the little-known intervention in Iran (in concert with the British), and the steamroller assault into Manchuria, the Kuriles and Korea.

Edele disabuses the notion that some still have that the USSR was a“Russian” empire: He notes that Stalin, a Georgian, spoke heavily accented Russian, and his sources include those of German, Jewish, Korean, Lithuanian and Polish ethnicity. And of course, it stretched across the breadth of the Eurasian land mass, from Europe to the eastern edge of the continent.

Edele joins other noted historians – such a Niall Ferguson, in 2012's War of the World – who have, in recent years, argued for a more Asia-centric interpretation of World War II than has customarily been the case in conventional Anglosphere histories.

Japan and Czarist Russia had clashed in 1905, long before the Communists seized power, and Stalin was always uneasy about his Far Eastern flank. His early-war support for Nationalist China in 1937, which included the undercover provision of Soviet fighter pilots who actually flew in combat, was a hedge against militarist Japan.

And one of the typically ruthless tactics that the ever-paranoid dictator pioneered in the east in 1937 would be mirrored in the final skirmishes in the west in 1949.

The first mass deportations of Stalin's rule were of ethnic Koreans – who he suspected of spying for Japan – from the sensitive Russian Far East to Central Asia. The last wave of deportations jerked away local popular support from the last anti-Soviet guerilla holdouts in Eastern Europe.

In all this, Stalin had prescience: He recognized as early as 1929 that, with the USSR established as the only socialist state on earth, war was inevitable. But his thinking, mingling revolutionary, imperialist, nationalist and strategic doctrines, was muddled, and his tactics to prepare for war, Edele notes, were“ambiguous.”

Many training programs in the early 1930s, such as for elite mountain troops and for stay-behind partisans, were far-sighted, but were upended in the Great Terror of 1937-8. Likewise, a stockpiling of weaponry in the early-mid 1930s may have appeared sensible, but the weapons were out of date by the 1940s. However, the experience of mass production would pay dividends once Hitler invaded and an arms race ramped up.

Starting with what might feasibly be called the first battle of World War II – at Lake Khasan/Chankufeng Hill, in Manchuria in 1938, where twice as many Soviet as Japanese soldiers fell – the Red Army's wars all finished in victorious end-games.

Those victories, however, came at an appalling cost in blood. Much responsibility for this huge butcher's bill lies in the hands of Stalin – notably his pre-war purges of the Red Army's senior ranks and his stubborn refusal to believe that Hitler was about to invade.

Purges seriously weakened the Red Army's professional abilities. It was“effective without being efficient,” Edele summarizes – an analysis he applies to other areas of Stalin's empire, such as industry.

So how did the USSR beat the previously unbeatable Germany and its Axis allies?

Red Army troops advance through the ruins of Stalingrad. Photo: RIA Novosti Archive/Wikimedia Commons

Why Stalin won

The short answer was because it had“more men, and way more horses, machines and guns,” Edele writes.

The 1941 shift of Soviet production away from the advancing invasion front would“permanently shift” the USSR's center of economic gravity. It would also out-perform Germany, which only put itself and occupied Europe onto a full economic war footing in 1944.

Post-war, many have blamed the weather and the immensity of the USSR, rather than Soviet resistance, for German failure. Yet Edele demolishes the myth that the Red Army collapsed in the early months following the German invasion.

Certainly, it was out-skilled by the invader. But“Ivan” fought with toughness, tenacity and relentless counter-attacks, wearing down the invaders' manpower and vehicles – as noted in vexed and increasingly worried German reports in 1941.

Edele also smashes the shibboleth that, on wheels provided by Lend Lease –“important but not essential” to the USSR, in his words – the Red Army was fully mechanized (as were the UK and US armies). In fact, near war's end, when the Red Army stormed Japanese-held Manchuria, it deployed twice as many horses as vehicles.

To make up for its mass of peasant cannon fodder, Stalin's army created crack units – around 20% of the overall force – who were the best trained, best led, best equipped and most mobile.

These“swift sword” corps had the best Soviet weapons, some of which would become iconic: the hardy submachines guns, the excellent T34 tanks and the overwhelming rocket and heavy artillery. Thus manned and armed, they conducted mobile“deep operations” that carved up the Wehrmacht.

None of these steps prevented catastrophic casualties among Stalin's poor bloody infantry. Even so, casualty ratios shifted as the Red Army's skillsets improved. In 1941, it took 10 killed or missing“Ivans” to kill a single“Fritz.” By 1944, that ratio was nearly even.

That so many troops were engaged – including female combat soldiers – is a testament to Communism's ability to mobilize. Surprisingly, many wartime Soviet citizens would experience greater freedoms and empowerments than they had in peacetime, Edele writes. In an existential struggle, ideological purity was of less import than competence, in both trench and factory.

In his demands for resistance, Stalin was canny enough to leverage more emotive motifs than ideology: In his first radio address after Barbarossa, Edele notes, he used the Orthodox Church form of address (“brothers and sisters”) and appealed to classic patriotism.

Stalin's terror proved double-edged in wartime. It liquidated opposition and provided policing, military policing and propaganda models that would ensure loyalty in the war against Hitler. But its lethality, combined with the poverty and misery so many had endured under Soviet control, also led many Soviets in overrun territories to initially welcome Germans as liberators, Edele records.

What saved Stalin, the USSR – and arguably, Western European democracy – was an irony of appalling brutality.

Adolf Hitler had expected that his invasion would precipitate a re-run of the Russian collapse of 1917-18. In actuality, the murderous German policies in the occupied territories soon convinced the Soviets that Hitler's genocidal Nazism was no better an alternative to Stalin's ruthless Communism.

One illustration of this paradox that Edele records is the pre-war forced deportation of tens of thousands of Polish Jews eastward. Harsh though it was, it had an unintended and fortuitous consequence: saving them from almost certain murder at the hands of Hitler's death squads.

Nazi brutalities provided a propaganda bounty for Stalin. They were effectively exposed in Soviet media to a first disbelieving, but subsequently stunned and infuriated populace.

A photograph that captures the horrors of the Russian Front shows a makeshift defensive position near Cholm: A barricade of frozen corpses. Photo: Bundesarchiv

Stalin's achievements, Soviet sufferings

Multiple post-war historians have pointed out that the destruction of three-quarters of German forces between 1941-45 by the Red Army was an achievement that the casualty-averse Western Allies could never have equaled.

But Stalin's war achievements – which extend beyond his marshalship to the political-diplomatic sphere – were broader, according to Edele.

One key achievement was the Soviet victories – Pyrrhic though they were – in the little-known 1937-39 conflict with Japan, and the subsequent neutrality pact signed with Tokyo. That pact held until the very last week of the conflict, when – with Germany safely defeated – Stalin broke it and unleashed the Red Army upon Manchuria.

It had been in the Far East where the doctrine of deep operations – which would later win especial fame in the massive German defeats of Stalingrad and Operation Bagration – had first been honed by Stalin's ablest general, Georgy Zhukov.

Zhukov's 1939 victory at Khalkin Ghol/Nomonhan on the Mongolian/Manchurian frontier – where 25,000 Japanese were lost – compelled Tokyo to conduct a“southward” strategy against European and US powers in the Pacific, rather than a“westward” strategy against the USSR.

Operationally, the release of Japanese pressure on the Russian Far East enabled the redeployment of fresh Soviet troops from that sector to the successful defense of Moscow in December 1941.

So strategically, Stalin evaded a two-front war – arguably, Hitler's worst blunder.

All this shatters the commonly held belief in English-language histories that the USSR had little influence on World War II's Pacific Theater. In actuality, the ramifications of Stalin's maneuvers in the Far East were beyond profound.

Stalin's other great achievement, in Edele's view, was convincing the Western Allies that Eastern Europe, post-1945, should be the USSR's backyard.

That understanding held for decades and was (very largely) honored until the collapse of the USSR and the Warsaw Pact in the early 1990s.

Few would bemoan those collapses – most notably those in the Baltics and Eastern Europe whose post-war independence was sacrificed to Soviet rule. But now, at the time of writing, the lack of a Brussels/Washington-Moscow modus vivendi, and the related issue of Russia's sphere of influence, haunts the world once more – as witness the Ukrainian crisis.

Yet, however crafty Stalin may have been as a strategist, the price the Soviet people paid in suffering, at the hands of both their enemies and their leadership was, in quantative terms, unparalleled in the history of humanity.

The USSR suffered 27 million dead, or 12% of its pre-war population. And Edele tells us that the killing did not end with the fighting. A murderous famine stalked the ruined lands of the USSR in 1946-7, killing another 1-1.5 million.

In World War II's forgotten campaign, Soviet tanks halt their advance in Manchuria in the final days of World War II to chat with locals. Photo: AFP

Lessons for historians, lessons for humanity

Perhaps the only real criticism of Edele's work is that it is too short, at 257 pages (of which 64 pages are appendices, notes and index) to do its vast themes full justice.

The last chapter, examining legacies across the former Soviet Union, could well have been expanded. Edele recalls a curious echo of World War II: The culture of allotment“victory gardens,” which sprung up during the war, lingered on and enabled millions to survive the chaotic early 1990s, after Soviet state distribution mechanisms had collapsed.

Yet Vladimir Putin, who dragged post-Soviet Russia back to its feet and under whose governance victory in“The Great Patriotic War” has been massively extolled, is not indexed. Nor, for that matter, does the book delve into the deep origins of much recent mischief on the Russian borderlands in Chechnya and Ukraine.

But there is far more to praise here than to criticize.

Unlike innumerable historians of World War II, Edele has no discernible ax to grind – be it ideological or nationalistic. Despite being an academic, his narrative races along in the style of popular history, with plentiful (and usually heart-breaking) first-person color.

Easy to digest, it is logically structured with chapter sub-headings, and though it is not bogged down with footnotes, is so packed with information it makes a fine reference work. It is a dense read, bristling with“Aha!” moments – from striking anecdotes, to telling statistics, to sharp analyses.

The book's maps – an irritating Achilles Heel of the publishing world – are clear, comprehensible and comprehensive, covering everything from battlefronts to deportation and lead-lease routes.

In short, Edele delivers plentiful bang for his reader's buck – or rather, ruble. And his work is recommended reading.

For students of history and strategy, Stalinism at War broadens our perspective of the vastness and multiplicity of timelines and front lines the Soviets fought over during the mightiest war, ever.

For students of the human condition, Edele's saga of oppression, deportation, massacre and battle makes clear how facile our Covid-era woes are compared to the staggering sufferings endured by a generation whose last, few survivors still share the earth with us.

That latter understanding is particularly germane at this time – the season of goodwill that concludes the 80th anniversary of the year when the hinge of fate turned at the gates of Moscow.

A Soviet officer urges his troops into the attack. Photo: Wikipedia CommonsMENAFN31122021000159011032ID1103468369