Latest stories

US bases woefully exposed to Chinese missile attacks

Biden, Xi taking lumps for allies' bad behavior

How Trump could push Japan, S Korea to go nuclear When we look at how Japan got all those immigrants, we see that it was a very deliberate result of government policy. Here is what I wrote for Bloomberg in 2019 :

And this is from a recent article in the Spectator :

Gearoid Reidy (who is very good at busting myths about Japan) has

another great article about this .

The reason the government is doing this is in order to compensate (partially) for Japan's rapidly aging society. Japan needs workers to support its industries, and taxpayers to support its pensions.

But if the general Japanese populace was opposed to this increase in immigration, they would put a stop to it - just as they put a stop to attempts to revise the country's constitution. The Japanese government is generally very responsive to public opinion. And public opinion in Japan is pretty pro-immigration.

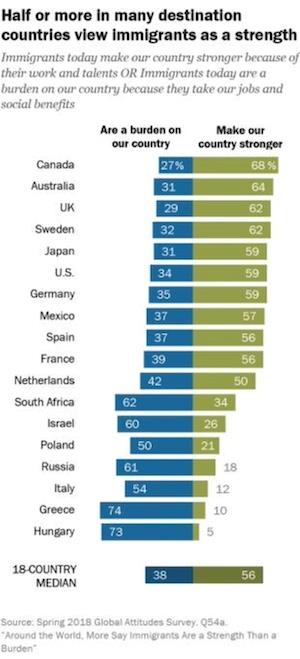

Japanese attitudes toward immigration There are numerous polls that ask Japanese people what they think about immigration. My favorite is the Pew survey, which asks the same questions to people in a bunch of developed countries. Here's some data from the 2019 survey :

Source: Pew According to this poll, Japan is not the most pro-immigrant country in the world, but it's near the top. In fact, the Pew survey asks many different questions, regarding crime, terrorism, mass deportation of illegal immigrants, and so on. In every single one of Pew's questions, Japan is more pro-immigrant than the median country surveyed.

Pew's is not the only poll, of course.

Gallup surveyed a much wider array of countries

than Pew did, and found that Japan was still well above median - about the same as France, and ahead of Brazil - in terms of openness to immigration.

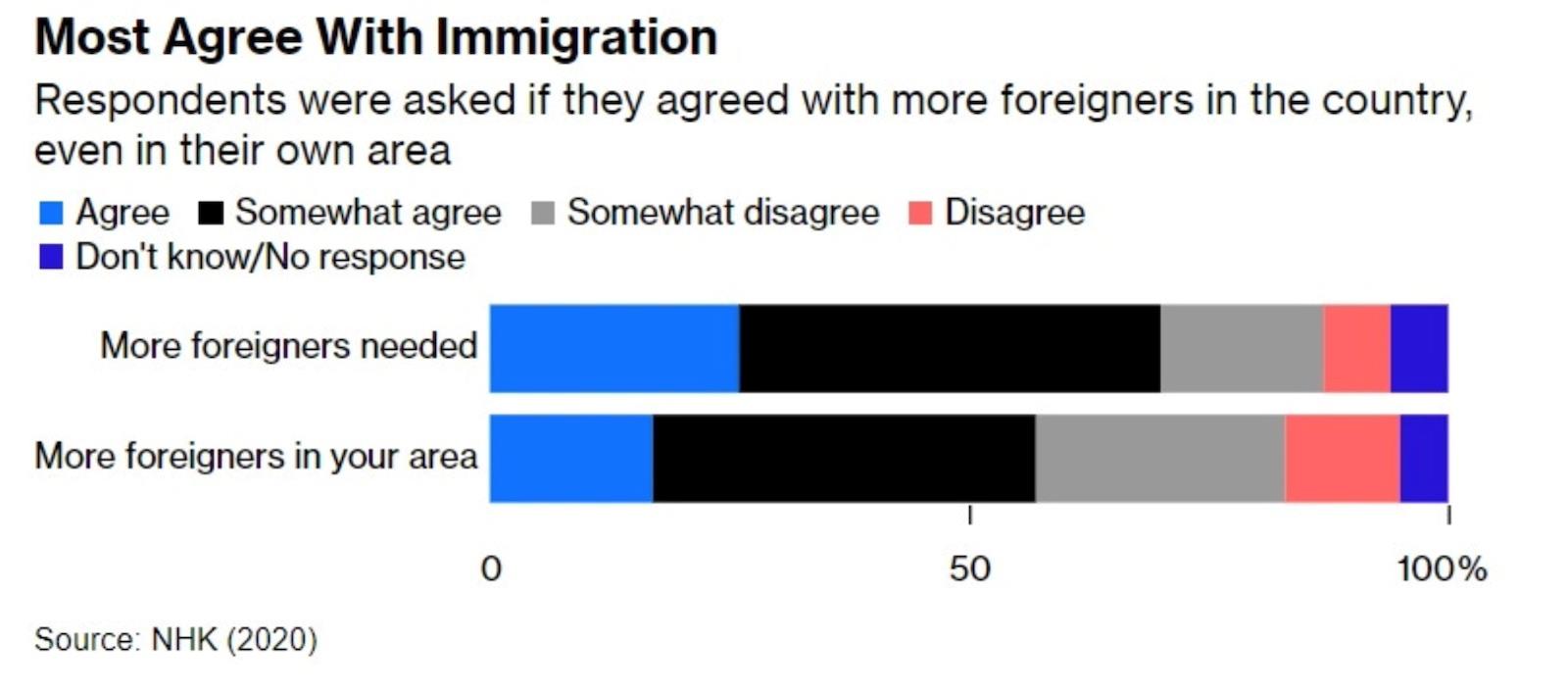

Do Japanese people want immigrants in the local areas where they themselves live? Yes. Kyodo News found that most Japanese prefectures want to add immigrants, in order to keep their communities from disappearing. And here's a poll by NHK:

Source: NHK via Gearoid Reidy Nor is the reason for the pro-immigration sentiment a mystery. It's just economics. Here's the result of a Nikkei survey :

The Nikkei survey did find some trepidation about the changes among the populace - 50% of Japanese people said they didn't like that the country had to welcome in large numbers of foreign workers, but that it couldn't be helped. But whatever unease Japanese people feel about the rapid diversification of their country, it

hasn't yet caused a political backlash

or any kind of visible intercommunal strife. America and most European countries can't say the same.

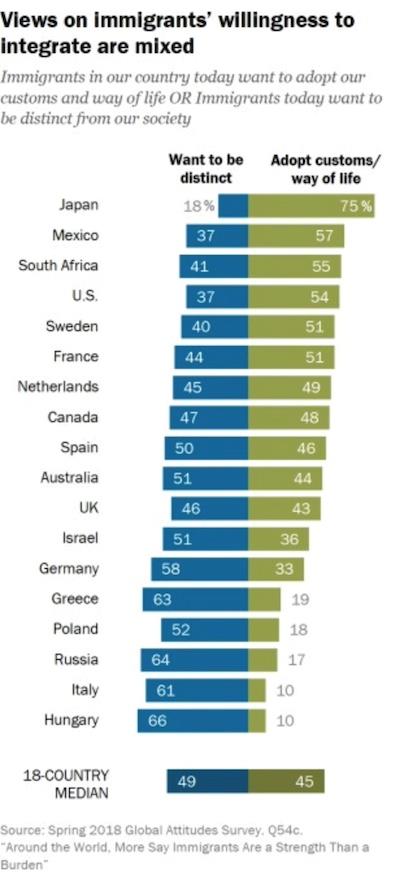

But when they're asked about specific concerns about immigrants, Japanese people are generally not very worried. For example, Pew finds that Japanese people are extremely confident that immigrants will integrate to their way of life:

Source: Pew How do we know Japanese people aren't just being politically correct when they answer these surveys? Igarashi and Kagayoshi (2022) have actually done some research on this. They find that Japanese people actually think that being anti-immigrant is more politically correct, and are giving pro-immigrant responses in spite of what they think they ought to be saying:

This is a very interesting experiment, because it suggests that many Japanese people also buy into the idea that their country is closed to immigration, and are expressing their own pro-immigration opinions

in spite of

that stereotype. That in turn suggests a country whose attitudes have shifted substantially in the last few decades.

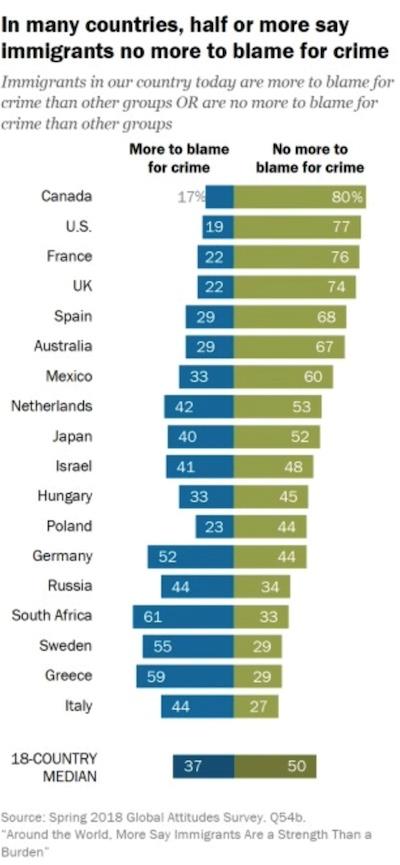

In fact, I should add that the average Japanese person is less worried about immigration to Japan than I am. I am personally worried that immigration will increase crime in Japan, because A) Japan is such an incredibly low-crime country to begin with that even immigrants who are very law-abiding by international standards will probably be more likely to break the rules, and B) Japanese corporations' rigid hiring system may systematically exclude some immigrants from economic opportunities, causing frustration among second-generation youth.

But my worry about crime is actually a minority viewpoint among Japanese people themselves:

Source: Pew In other words, every piece of systematic data we have shows that Japan's opening to immigration is being driven not by elite machinations, but by broad-based public opinion.

Anecdotes and impressions Japan's xenophobia may be largely a thing of the past, but the trope of Japan as a closed-off, stubbornly homogeneous nation seems to be deeply rooted in the Western psyche.

When there's a persistent stereotype like that, people tend to A) come up with creative interpretations of evidence in order to protect that stereotype, and B) seize on anecdotes, real or false, that seem to confirm the stereotype.

As an example of the latter, a lot of people on social media claim that there are a bunch of restaurants and other establishments in Japan that refuse to serve foreigners. If you do a Google search for this, you will find a huge number of people asking about it.

In fact, there are a very, very few restaurants in Japan that do refuse to serve foreigners. Once in a very great while, someone finds one of these and puts a picture of it on Twitter or Reddit, and it makes its way around the internet and reinforces everyone's stereotypes. But the truth is that this sort of thing is incredibly rare. I've never encountered it. No one I know in Japan has ever encountered it.

Like certain other

notorious urban myths

about Japan, restaurants that refuse to serve foreigners are almost entirely apocryphal. The myth is perpetuated by A) people lying on the internet, B) gullible Westerners' willingness to believe in a myth that conforms to their stereotypes, and C) tourists encountering restaurant hosts who can't speak English, and assuming they were turned away for being foreign.

Another example of confirmation bias is when Americans come back from a trip to Tokyo and tell me how homogeneous it was. They tend to assume that all the East Asian people they see riding the train or

working in convenience stores

are Japanese, rather than Vietnamese or Chinese or Filipino immigrants (which

a substantial portion are ).

And when they see White or Black or South Asian people, they tend to assume they're tourists instead of residents. The large number of Indian people working at Narita airport may be changing that perception, but in general, it can be easy to ignore the diversity around you if you start by assuming it doesn't exist.

In fact, after living in Japan for about four years, my own impression is that Japanese society is roughly as welcoming to immigrants as the US is.

In some ways, it's more accepting. On occasion I've seen Western expats treat Japanese service workers like dirt with zero repercussions - a phenomenon colloquially known as the“gaijin smash.” The same forbearance would not be shown in most of the places I've lived in America.

Yes, some Westerners living in Japan will tell you that they never quite felt accepted,or like they fit in. To be frank, I think this is usually some combination of A) failure to learn Japanese and B) being the type of person who wouldn't feel accepted in their home country either. If I were you, I would not accept these tales as evidence of Japanese xenophobia.

And yes, occasionally you will hear an elderly, right-wing

Japanese politician declare

that Japan is a racially homogeneous nation. You should treat this exactly like you would treat someone like Marjorie Taylor Greene or Louie Gohmert declaring that America is a Christian nation, or someone like Stephen Miller claiming that the children of immigrants will never become truly American.

I know that there are a lot of people who are not going to be convinced by this post. Stereotypes are beloved, cherished things, and the impulse to explain the world through cultural essentialism is deep-rooted and strong.

There is a certain segment of the population who is always going to believe that Japanese people are still a bunch of 18th-century samurai, contemplating the cherry blossoms as they polish their swords. Old canards survive because they're comforting - they're easy shortcuts toward the feeling that we've somehow made sense of a complex and fast-changing world.

So you know what? If after seeing all of the evidence, you're still firm in your conviction that Japan is a closed-off, xenophobic society,

don't move there. Both you and Japan will be better off as a result.

Sign up for one of our free newsletters The Daily ReportStart your day right with Asia Times' top stories AT Weekly ReportA weekly roundup of Asia Times' most-read stories

But if you're the president of the United States, or another important figure in the US government, please refrain from calling Japan xenophobic. If you're going to be wrong about this, at least be wrong silently.

Update : As if to underscore my point, Japan just doubled its annual cap on visas for skilled foreign workers, from 80,000 to 160,000. As a percent of Japan's population, this is larger than the US caps on employment-based green cards and H-1b visas combined.

This article was first published on Noah Smith's Noahpinion Substack and is republished with kind permission. Read the original and become a Noahopinion subscriber here.

Already have an account?Sign in Sign up here to comment on Asia Times stories OR Thank you for registering!

An account was already registered with this email. Please check your inbox for an authentication link.