Flicker Of Hope For Cambodia's Rubbed Out Opposition

“We can only ask and appeal to those who love democracy and our nation to unite with the Candlelight Party,” declared Thach Setha, president of the surging opposition group as Cambodia gears up for local elections on June 5.

Just months ago few observers thought the party, which had been moribund since 2012, stood a chance of competing against the country's dominant Cambodian People's Party (CPP), which controls all but one commune chief post and every other political office nationwide.

Formerly known as the Sam Rainsy Party, eponymously named after Cambodia's main opposition leader dating back to the 1990s, the Candlelight Party only restarted its political activities last October. But some now reckon it has a shot of weakening the CPP's monopoly of locally-elected posts, which could act as a springboard for general elections in July 2023.

More than 5,000 people attended the party's special congress on May 15 to decide on a seven-point campaign manifesto. Party organizers had only expected 2,000 attendees, according to reports. Despite widespread CPP supporter intimidation, the Candlelight Party will field candidates in all but a few of the country's 1,652 communes, making it by far the second-largest party going into the ballot.

Few, of course, expect the revived party to win. The ruling CPP, in power consecutively since 1979, has had a stranglehold on politics for the past five years. In November 2017, its court proxies forcibly dissolved its main opponent, the Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP), which was spuriously accused of plotting a US-backed coup.

All CNRP MPs were kicked out of parliament and many fled the country fearing for their personal safety. The CPP subsequently took all parliamentary seats for itself at a rigged 2018 general election. Sam Rainsy, previously a CNRP leader, has been in self-exile since 2015.

Cambodian opposition leaders Sam Rainsy, front left, raises the hand of co-CNRP leader Kem Sokha in 2014. Photo: AFP / Tang Chhin Sothy

Kem Sokha, the CNRP's other leader, was arrested for treason in 2017 and his trial is ongoing nearly five years later. In a wide-reaching anti-democratic clampdown, activists have been arrested, free media shuttered and protests of any stripe largely banned.

As party registration ended earlier this month, the National Election Committee (NEC) announced that the Candlelight Party will field candidates in 1,632 of the country's 1,652 communes at next month's ballot. The party itself says it has registered 1,649 candidates.

That gives it the highest number of candidates other than the ruling CPP, which will put up a list of candidates for each of the 1,652 communes. The third-largest party will reportedly only field candidates in around 40% of communes.

Local elections often serve as bellwether tests for voter sentiment at upcoming general elections. Commune councilors also elect district, provincial, and municipal councils, as well as have a say over who sits in the Senate.

Analysts point to growing intimidation by authorities as a sign that the CPP sees the revived opposition party as a threat. In recent days, the ruling party has leveled all manner of accusations against Candlelight Party candidates. Some have been banned from competing by the NEC, while pro-government media is on the attack as a two-week campaign period began on May 21.

The Candlelight Party traces its history back to 1995 when Sam Rainsy, a former finance minister, founded the Khmer Nation Party. Its name was later changed to the Sam Rainsy Party (SRP), which was the main opposition group from the late 1990s until 2012 when Rainsy and Kem Sokha formed the CNRP.

The SRP continued to operate independently since it controlled seats in the Senate. It was renamed the Candelight Party, after the party logo, in 2017 as the government introduced new laws banning eponymously-named parties.

Rainsy, now in exile in France, has consistently distanced himself from the party. Local laws mean that a party can be dissolved by the courts if it has any association with convicted criminals. Rainsy has numerous politically-motivated charges against him.

“In Phnom Penh, my slightest word or gesture is watched for any sign of support for the Candlelight Party so as to find a pretext to dissolve it,” Rainsy wrote in an article in April.

The party's re-emergence has not been without controversy. In 2012, the CNRP's formation was supposed to be a“merger” between Sam Rainsy's eponymous party and Kem Sokha's Human Rights Party, then the third-biggest political outfit. Even after the CNRP's forced dissolution in 2017, the agreed plan was to leave the CNRP moribund at home but active abroad until leaders could find a way of legally restoring it.

But Sokha and his supporters reacted furiously when the Candlelight Party resumed its activities last October while the CNRP was still banned, with some party members accusing Rainsy of going behind the backs of his CNRP colleagues.“I would also like to affirm that I am not involved in and not responsible for the activities of Mr Sam Rainsy and his group,” Sokha wrote on his Facebook page last November.

Supporters of the now-banned Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP) gather in a rally on the last day of the commune election campaign in Phnom Penh on June 2, 2017. Photo: AFP / Tang Chhin Sothy

In the eyes of Kem Sokha's followers, the Candlelight Party's resumption spells the final rupture of the CNRP, which has always been cleaved between the two leaders' factions. Neither does it help that the Candlelight Party routinely namechecks the CNRP, implicitly presenting itself as the successor.

Thach Setha, the Candlelight Party's president, noted recently that it will“use our old policies, [and] add some of the commune policies of the CNRP…because the stance of the Candlelight Party is not different from that of the CNRP.”

Kem Sokha, who still awaits a court judgment on treason charges, is barred from politics, although many analysts suspect he may accept a royal pardon deal from Prime Minister Hun Sen on the proviso he leads a restored but servile CNRP.

On the one hand, the Candlelight Party's history serves it well. At the last general election it contested before the CNRP's formation, SRP won a fifth of the popular vote. The party machine is clearly well-oiled and lacks the structural problems that many newly-formed parties face. Its campaigners and organizers have been doing their work for years.

Thach Setha is a veteran of both the SRP and CNRP. Son Chhay, the party's vice-president, is one of the country's most respected opposition politicians, having previously served in parliament between 2003 and 2017, including as the CNRP's chief whip.

Moreover, the party has selected many new faces as candidates, giving it a fresh upstart image. Many Cambodians sense the party has the approval of Rainsy, who is still widely seen as a pro-democracy icon who has jousted with the authoritarian Hun Sen for literally decades. As Rainsy wrote recently:“There is nothing to stop me offering moral support without any active involvement with the party.”

Yet the big question mark is whether the Candlelight Party will be able to woo CNRP supporters who side with Kem Sokha's aggrieved faction.“We are not sure whether supporters of the dissolved CNRP will support the Candlelight Party, given the split between Candlelight Party supporters and those supporting Kem Sokha and his former Human Rights Party,” says Kimkong Heng, a visiting senior research fellow at the Cambodia Development Center.

It isn't inconceivable that Kem Sokha's faithful with either boycott the ballot or try to diminish the Candlelight Party's flame, perhaps in retaliation for what they perceive as Rainsy's faction breaking ranks. They could vote instead for Funcinpec, the once-dominant royalist party, or the Khmer National United Party (KNUP), a Funcinpec breakaway.

Those two parties are fielding the third and fourth-largest number of candidates, respectively. Nhek Bun Chhay, the KNUP leader, currently holds the only commune chief position not controlled by the CPP.

Cambodia's Prime Minister Hun Sen (C) prepares to cast his vote during the general election as his wife Bun Rany (L) looks on in Phnom Penh on July 29, 2018. Photo: AFP / Manan Vatsyayana

There are already questions about how free and fair the upcoming commune election will be. The Asian Network for Free Elections said in its pre-election analysis that the ballot is unlikely to be“fair, credible, transparent, inclusive, and peaceful.”

The CPP controls the NEC, which decides everything about how the election is managed and tallied. The League for Democracy, an opposition party that came in third place with around 5% of the vote at the 2018 general election, says it will boycott next month's ballot because it opposes how the NEC is managing polling stations.

Some are already asking what would constitute success for the Candlelight Party considering the extraordinary odds stacked against it“I would be looking for anything remotely similar to the CNRP performance of the past to indicate that the Candlelight Party is the real heir-apparent,” says Sophal Ear, associate dean and associate professor in the Thunderbird School of Global Management at Arizona State University.

At the last local elections in 2017, held just months before its dissolution, the CNRP took around 43% of the popular vote and ended the CPP's monopoly on commune posts for the first time since local elections began in 2002.

A more achievable benchmark would be to replicate the 2012 local election result when the SRP won 20% of the vote. If it could achieve a comparable tally, the Candlelight Party will show it's now the main opposition force, and perhaps convince some of Kem Sokha's faithful to give it a democratic chance.

Some analysts reckon the Candlelight Party may also attract voters from some of the 16 other parties contesting the commune elections, which would give the party a better shot at next year's general election.

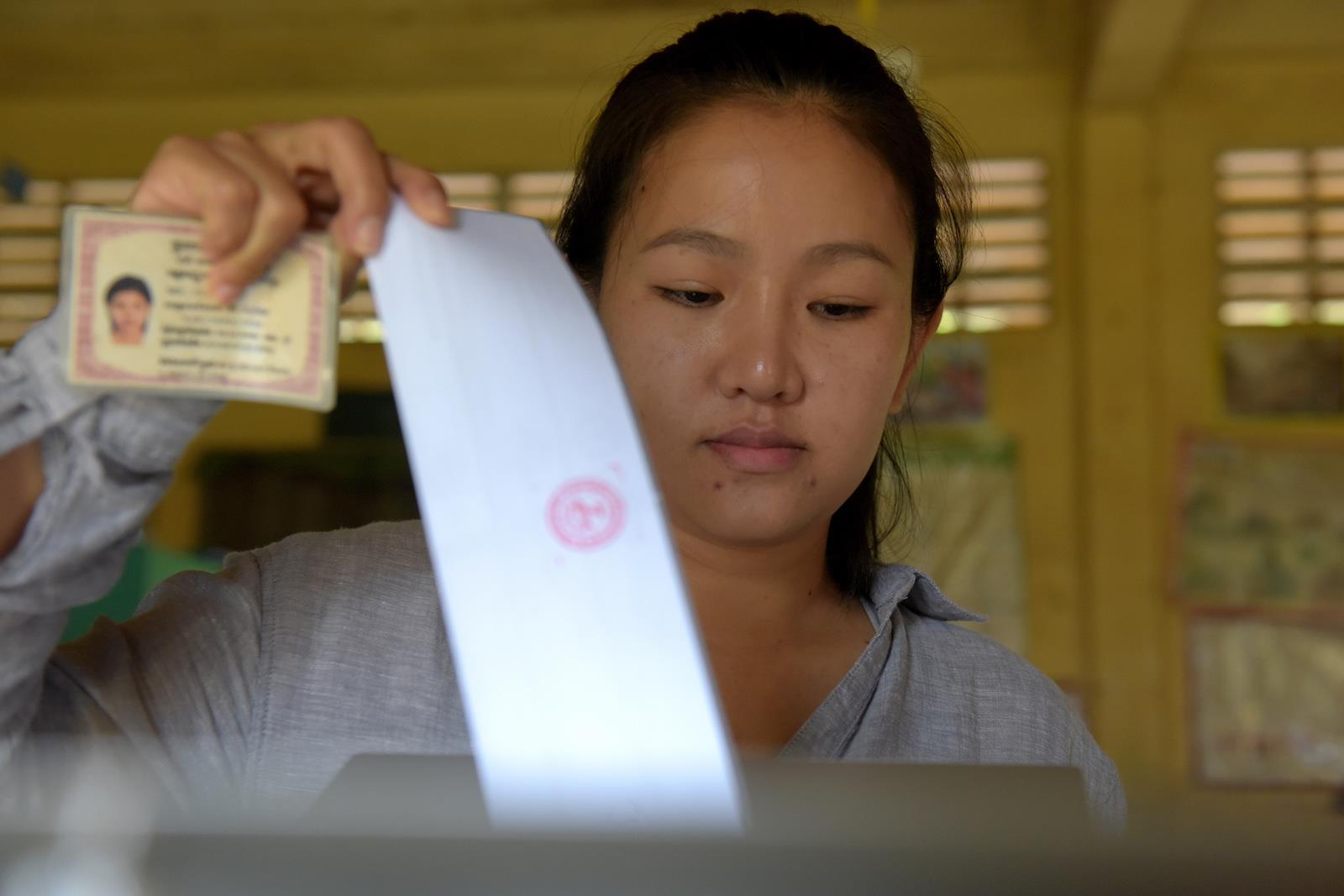

Little choice: A Cambodian woman casts her vote during the country's sixth general election in Phnom Penh on July 29, 2018. Photo: AFP / Tang Chhin Sothy

But even that could be a Janus-faced achievement. Academic Ear reckons a strong Candlelight Party showing next month will see the CPP“putting the kibosh” on the party before the July 2023 general election.

The CPP-dominated courts could easily find an excuse to dissolve the party, as its historical association with Rainsy hangs like a Damocles Sword over the party. The CNRP, after all, was forcibly banned just months after it made inroads at the 2017 local elections.

Then, many pundits reckoned the CPP looked at its opponent's tally and thought it could have gone on to win the 2018 general election, so nipped its chances in the bud.“The opposition has been there before. Once bitten, twice shy,” Ear said.

Follow David Hutt on Twitter at @davidhuttjourno

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment