(MENAFN- Asia Times)

China's complacency after its 2020 success in containing COVID-19 led Beijing to neglect measures that would have made the tragic Shanghai lockdown avoidable. Once the highly-contagious new COVID strains hit Shanghai in early April, China had no choice but to lock down the city, with a cost in death and suffering that is yet to be fully tallied.

But the disaster could have been mitigated by the mass application of better vaccines, and by improvement in the AI-Big Data capacity that China applied with success in 2020, when the pandemic first emerged.

This is the conclusion of an exhaustive study by Asia Times using information from the World in Data of China's Covid-19 epidemic since its inception, which is summarized below in a series of graphics.

The Shanghai lockdown probably has bought China some time and avoided a national disaster that would have led to over 1.6 million deaths, according to a study released this week by Shanghai's Fudan University. But the respite will be temporary unless China takes drastic action of a different kind.

The trajectory of the world economy in 2022 depends to a great extent on whether China succeeds or fails in its next Covid response. China's leadership, moreover, will weigh the mistakes of the past year as it prepares for its quinquennial leadership selection at the next Communist Party Congress on October 20.

Basking in its success in containing the first wave of the epidemic in 2020, China failed to anticipate the impact of the jump in transmissibility of new virus strains, ignoring evidence that its domestically-produced vaccines were ineffective against the new mutations.

At the same time, Chinese authorities spent the past year undermining the big tech companies whose tracking apps and data analytics did so much to contain the outbreak in early 2020, rather than mobilizing them to adapt these techniques to the new variants.

The prevailing Omicron strain and its subvariants are four times as transmissible as the preceding Delta variant, and the virus reproduces 70 times faster in the upper respiratory tract, according to the present medical consensus .

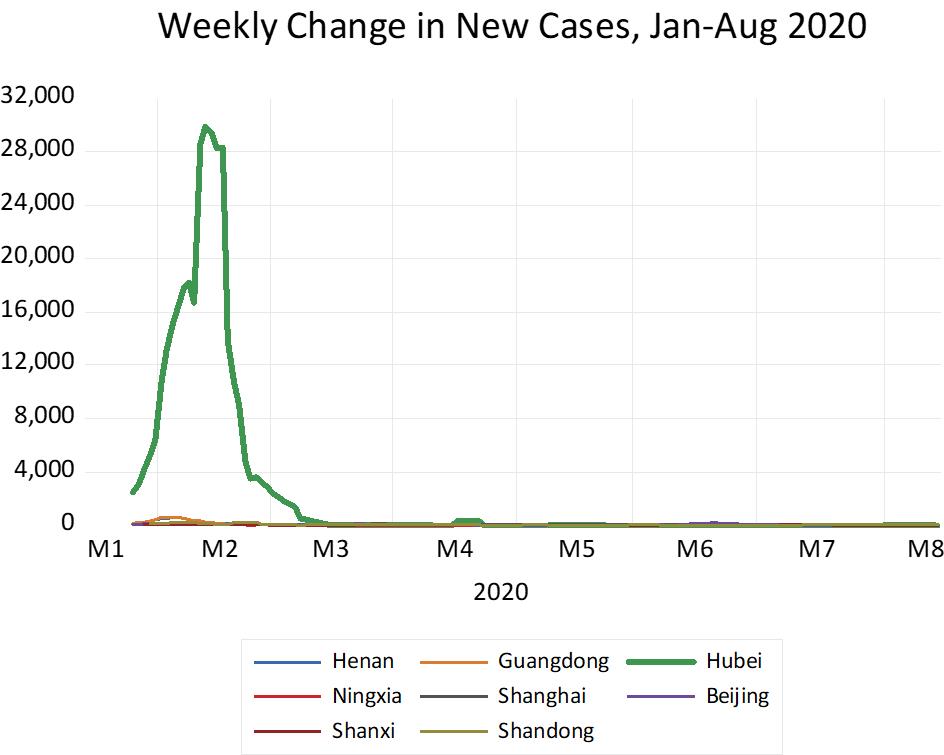

Region-by-region examination of Covid outbreaks in China makes clear how different today's crisis is from the first wave of infection in early 2020, when an epidemic in Hubei province's Wuhan City prompted a lockdown of the main locus of the epidemic, followed by minor outbreaks elsewhere.

Graphic: Asia Times

Asia Times was arguably the first news organization to report that AI/Big data analysis of locational information from smartphones was key to controlling China's initial outbreak.

“China used locational and other data from hundreds of millions of smartphones to contain the spread of Covid-19, according to Chinese sources familiar with the program,” we reported on March 3, 2020 .

“In addition to draconian quarantine procedures, which kept more than 150 million Chinese in place at the February peak of the coronavirus epidemic, China used sophisticated computational methods on a scale never attempted in the West.”

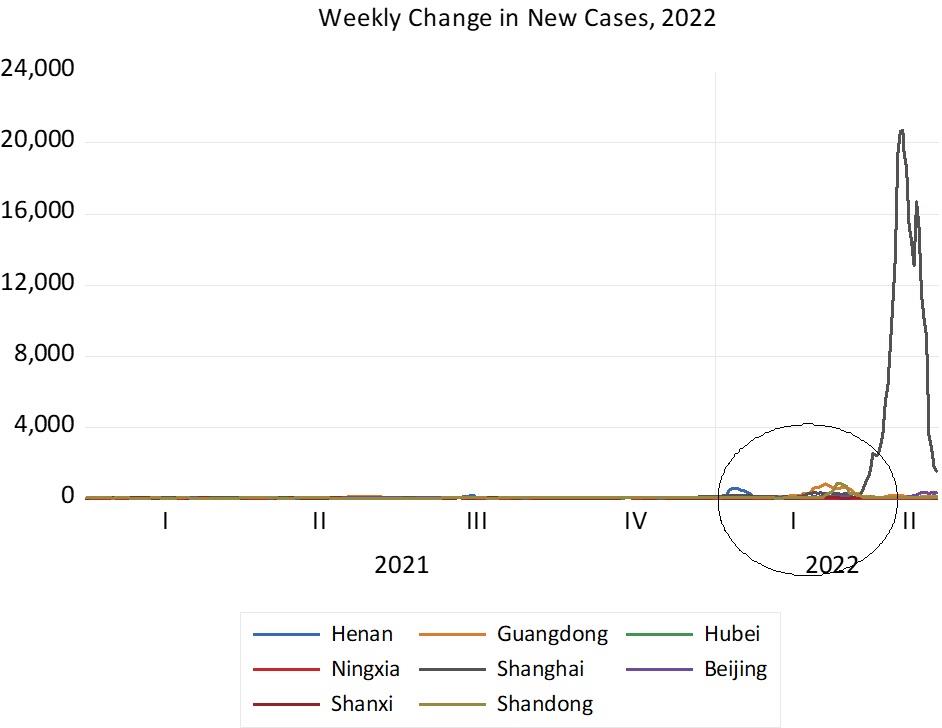

By contrast, the 2022 outbreak shows the opposite pattern: A small outbreak in Hubei (the original epicenter of the epidemic) anticipated an outbreak 1,500 kilometers away in Ningxia. That anticipated an outbreak in Shandong, on the other side of the country. And the outbreak then jumped another 900 kilometers from Shandong to Shanghai.

Graphic: Asia Times

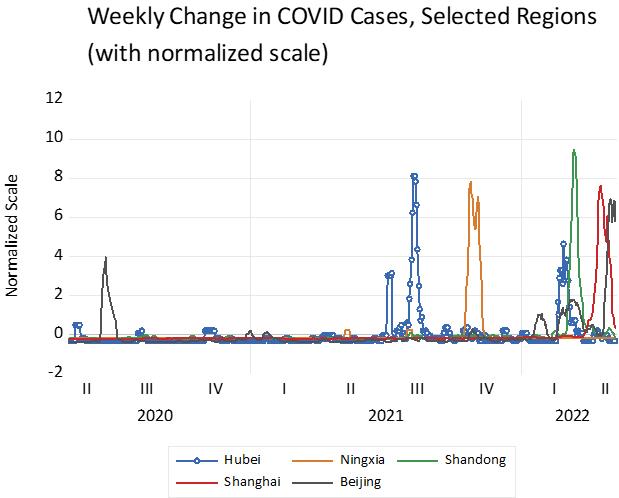

The picture becomes much clearer if the data is displayed on a normalized scale (that is, each line on the chart shows change relative to the normal levels for each province). We observe a pattern in which an outbreak in one province anticipates an outbreak in the next.

Graphic: Asia Times

Because the distances between the cities are so great and the absolute numbers of infections relatively small, the pattern was easy to miss. Statistical analysis, though, makes clear that each outbreak predicted the next.

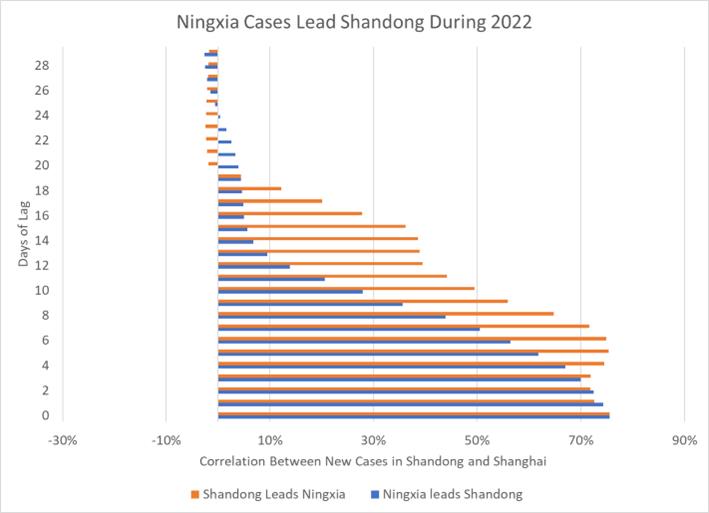

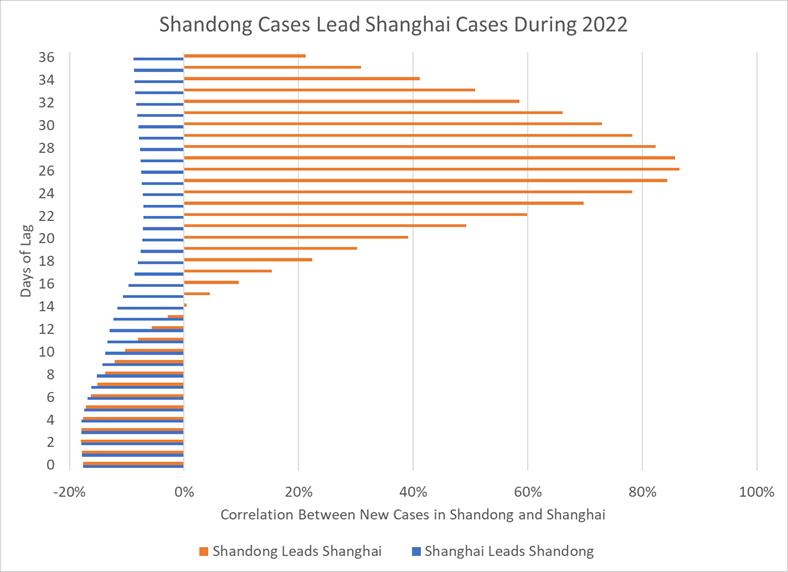

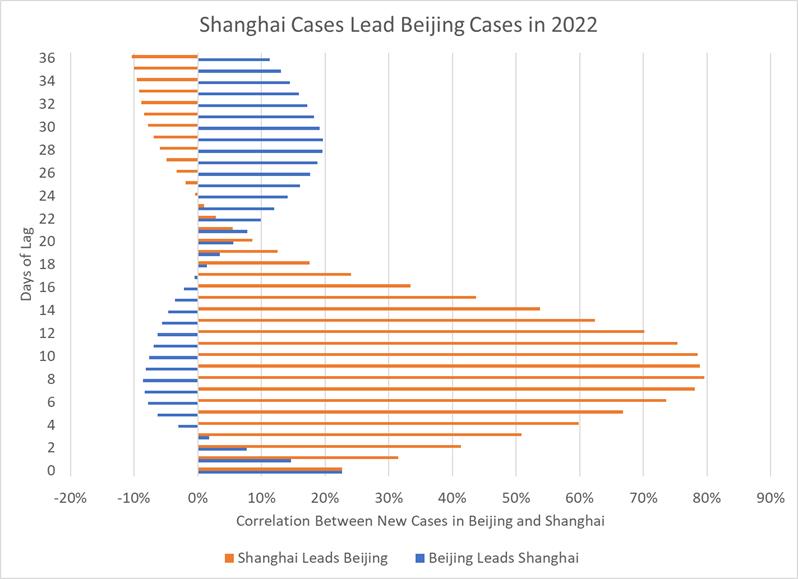

Below we show cross correlograms (graphic illustrations of the correlation between outbreaks in the different provinces at lags of 0 to 30 days). Correlation isn't proof, to be sure, but the consistent, repeated pattern of correlation makes it highly improbable that each outbreak did not cause the next.

That should have been a cause for a national alert in the first weeks of 2022. The fact that the new virus strains jumped so easily between provinces over great distances strongly suggests that a small number of travelers between cities carried the virus, and that the rate of transmission of this variant was perhaps an order of magnitude greater than the strains that China successfully suppressed in 2020.

Graphic: Asia Times

Graphic: Asia Times

Graphic: Asia Times

Graphic: Asia Times

Regression analysis shows that the leads and lags have a high degree of statistical significance. That means that it is very unlikely that the leading relationship is coincidental.

Why did the Chinese authorities miss the pattern? The actual number of cases in Hubei, Ningxia, and Shandong was in the hundreds, enough for local officials to ignore. But with Omicron and subvariants, contagiousness is so high that a spark can start a prairie fire.

Evidently, China's authorities grasped the magnitude of the crisis only after the case count began to climb in Shanghai. At that moment in time, there was no choice other than to lock the city down. The Fudan University study cited earlier concluded:

“The data show that if China 'lies flat' in terms of epidemic prevention and offers no defense against the Omicron strain, the country would suffer heavy losses. More than 112 million people would be infected, 5.1 million would be hospitalized, 2.7 million would be admitted to intensive care units, and nearly 1.6 million would die. Of these, about three-quarters of the deaths would be unvaccinated people over 60 years old.

At the peak of the epidemic, it is estimated that 1.57 million respiratory disease patients would require hospital, which is less than the total number of respiratory disease beds at Chinese hospitals (3.1 million). However, the 1 million intensive care unit beds needed at the peak of the epidemic would far exceed the number of existing intensive care unit beds in China (64,000), and it is estimated that the shortage of beds would take 44 days to alleviate.”

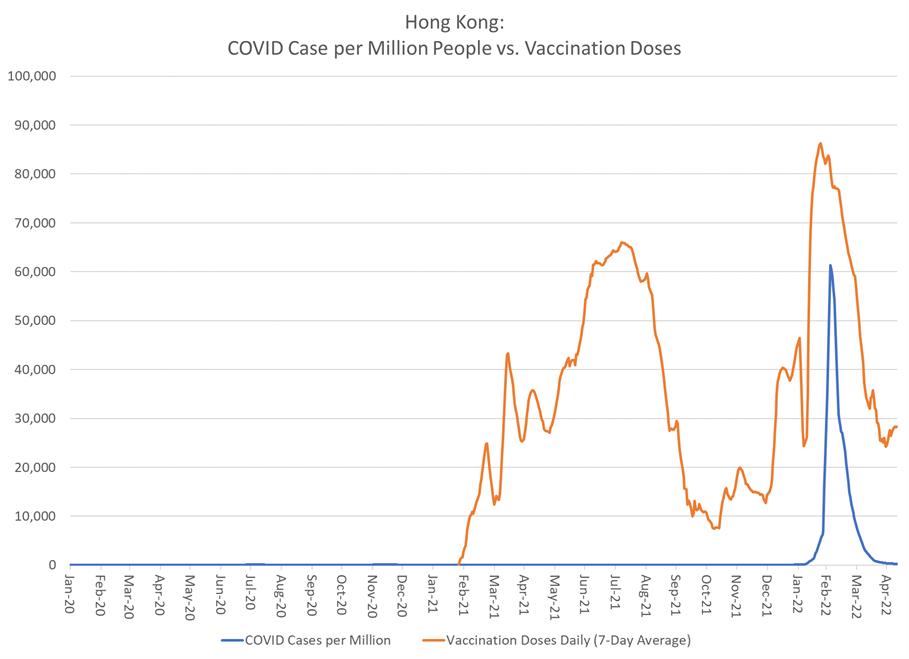

It might be objected that Hong Kong survived a major outbreak earlier this year without the painful lockdown imposed on Shanghai. But circumstances are vastly different. First of all, Hong Kong undertook a campaign of mass vaccination before the outbreak hit, using more effective mRNA shots made by Moderna and Pfizer.

Graphic: Asia Times

Second, Hong Kong did not have the same anticipatory shocks from other provinces that forecasted (or should have forecasted) the Shanghai outbreak. Third, Hong Kong controls travel in and out of its Autonomous Zone and requires quarantine of all new arrivals, unlike Chinese domestic travel.

China has now taken precautionary measures in Beijing, which has registered about 300 new Covid cases per week during the past eight weeks. It requires Covid tests for entry into public spaces, it is conducting mass testing with antigen kits, and it has suspended taxi services and some other public activities.

Chinese authorities are at pains to state that Beijing is not subject to a lockdown like Shanghai. We do not know how the situation on the ground in China's capital will develop. So what should China do now?

First, China should admit that the Sinovac vaccine is ineffective against Omicron and mobilize its resources for mass vaccination with mRNA vaccines, as Hong Kong did. That will take time and considerable resources, but it is an indispensable precaution.

None of the vaccines appear to prevent Omicron infection, but the mRNA dose significantly reduces the severity of symptoms and hospitalizations.

Second, and most important, China should mobilize its technology companies to expand the monitoring and analysis capability that they brought to bear at the first stages of the pandemic (as did South Korea and Taiwan).

Smartphones and smartwatches can monitor body temperature, pulse, blood pressure and blood oxygen levels, as well as perform electrocardiograms. It is now possible to monitor the vital signs of an entire population in real-time and transmit the data to the Cloud for further analysis.

No matter how effective the present lockdown might be, the virus will continue to lurk in the population, especially among individuals with low immunity to infection. AI analysis of big data sets made it possible to identify hotspots of infection in Chinese cities and to track individuals who might have been exposed to the virus. Those techniques helped China suppress the 2020 outbreak, as noted.

The Chinese government will need the resources of its Big Tech companies, which have the combination of computing and communications infrastructure as well as IT personnel, to advance these techniques to the level required to fight Omicron.

During the past year, the government's main interaction with Big Tech has been adversarial, as Beijing attempted to discourage monopoly practices by the internet giants. Although the government's concerns about internet monopolies had some merit, Beijing neglected the decisive contribution that the tech sector could have made to disease control.

Follow David P. Goldman on Twitter at @davidpgoldman

MENAFN13052022000159011032ID1104210490