(MENAFN- ING) Why is the US BoP important for FX?

We have not heard too much about the US current account deficit for quite a while. This is because unlike back in 2006 – when the US was running a deficit of 6% of GDP and the term 'external imbalance' was a hot one – the deficit is now a far more manageable 2.9% of GDP. And 2023 proved a good year for the deficit as exports improved relative to imports.

A smaller current account deficit is good news for the dollar and leaves it less vulnerable to the 'kindness of strangers', a problem that can occur when the current account deficits get too wide and foreign buying of domestic assets dries up. Away from the currency crises experienced in Argentina and Egypt, the higher-rated Chile comes to mind as a country recently suffering a Balance of Payments crisis. Back in 2022, its 10% of GDP current account deficit was far too wide, and despite the central bank spending half of its FX reserves in supportive intervention, Chile's peso still dropped 35%.

The reason we are looking into the US BoP is a more positive one in that we wanted to know whether the US deficit was increasingly being funded by foreign direct investment (FDI). For example, there are frequent news reports of foreign companies investing in the US to take advantage of either the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) or the Chips Act. Have these flows been material enough to show up in the FDI line item of the US Financial Account? If so, a higher proportion of 'sticky' FDI funding of the US deficit would be seen as more supportive of the dollar.

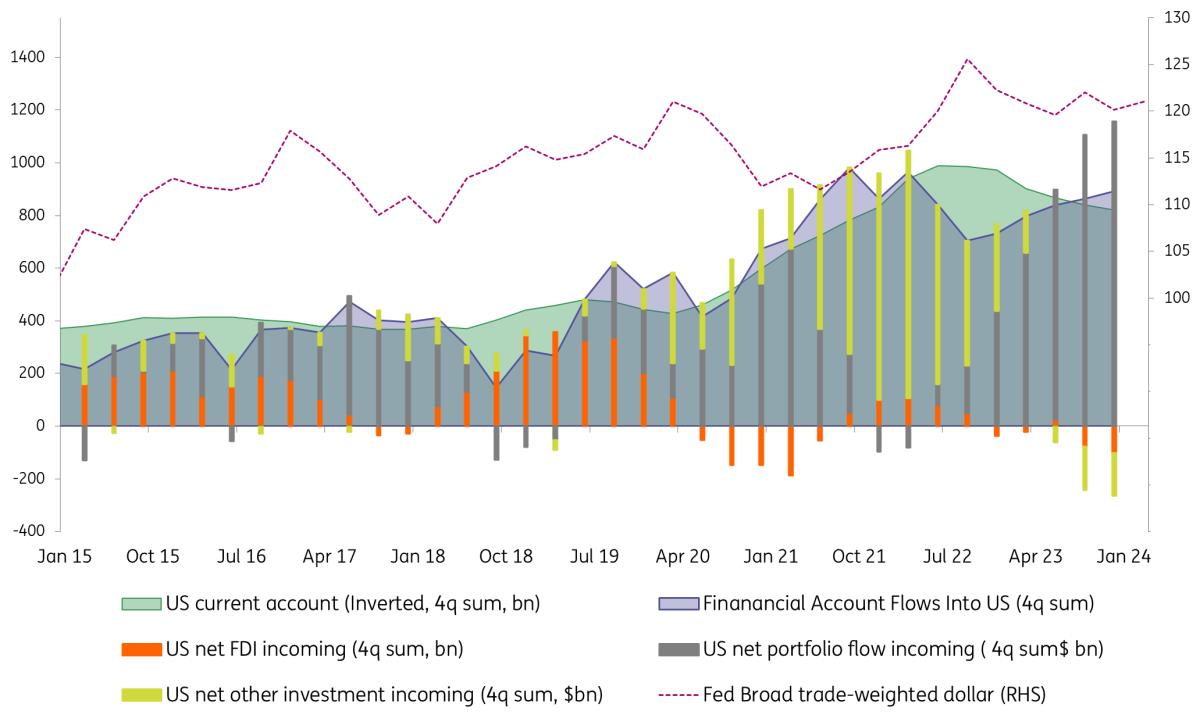

Our chart below looks at the US BoP in its broadest sense. In terms of observations to make (all data are four-quarter rolling sums), we can say:

The US current account deficit modestly narrowed in 2023 and is more than covered by Financial Account Inflows. These inflows are the aggregate of FDI, Portfolio Flows, and Other Investment.

Net FDI flows are actually running net negative for the US. This is a function of US residents sending more FDI overseas than the US is receiving in FDI.

The dominant line item in terms of the funding of the US deficit is clearly portfolio flows. This has been driven by strong foreign buying of US securities and weak US buying of foreign securities.

We now dig into this portfolio flow line item.

US Balance of Payments: Financial inflows more than cover the US C/A deficit

ING, Macrobond Portfolio flows: It's a debt not equity story

Above, we show that FDI has not made much difference to financial inflows to the US. If not FDI, perhaps the next best thing in terms of deficit financing would be flows into equity securities. Has this been the case? We have heard a lot about US exceptionalism – better US growth rates and better investment opportunities in US companies. Does the BoP data bear this out? Again, the answer here is no.

As our chart below shows, net equity inflows into the US have been quite modest in 2023. And in fact, the net inflow into the US in the fourth quarter last year was only down to US investors selling their overseas holdings of equities.

Instead, it is the foreign purchases of long-term US debt securities that dominate this portfolio line item. Long-term debt securities are defined as securities issued by the US Treasury, US Agencies (e.g., Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac) and the corporate sector. These securities have maturities of greater than one year.

This brings us to the conclusion that the attractiveness of US long-term debt securities is an increasingly important one to the financing of the US current account deficit, and potentially to the dollar as well. Because of inverted US yield curves, we would assume that the FX hedge ratios on foreign holdings of US debt securities lie towards the lower end of historical ranges. A big net sale of these US debt securities would likely prove a dollar negative. It has been very rare to see the dollar and US bonds sell off in tandem – but it has happened before.

And that should serve as a timely reminder that whichever party has the White House and Congress next January, maintaining the appeal of US bond markets will be paramount.

Long term debt securities dominate US portfolio inflows

ING, Macrobond And there is a naughtier twin in the high fiscal deficit

Regardless of the election outcome, both the current and incoming administrations have a sizeable fiscal deficit to contend with. Both sides of the aisle acknowledge the high deficit and nod toward possible remedial action(s). But neither side has credible plans for fiscal tightening. We're therefore liable to see the ongoing print of elevated coupons as nominal growth slows. This will ratchet up government debt levels relative to GDP, in turn raising the possibility for a sovereign downgrade.

On top of that, there is no term premium imputed into the 10-year Treasury yield currently. In other words, the level of the 10-year Treasury yield is nothing more than an extrapolation of rate expectations into the future, effectively an average of the funds rate plus a moderate risk-free rate to the short-term bill spread. So, holders of longer-dated Treasuries are not getting compensation for the risk being taken out the curve.

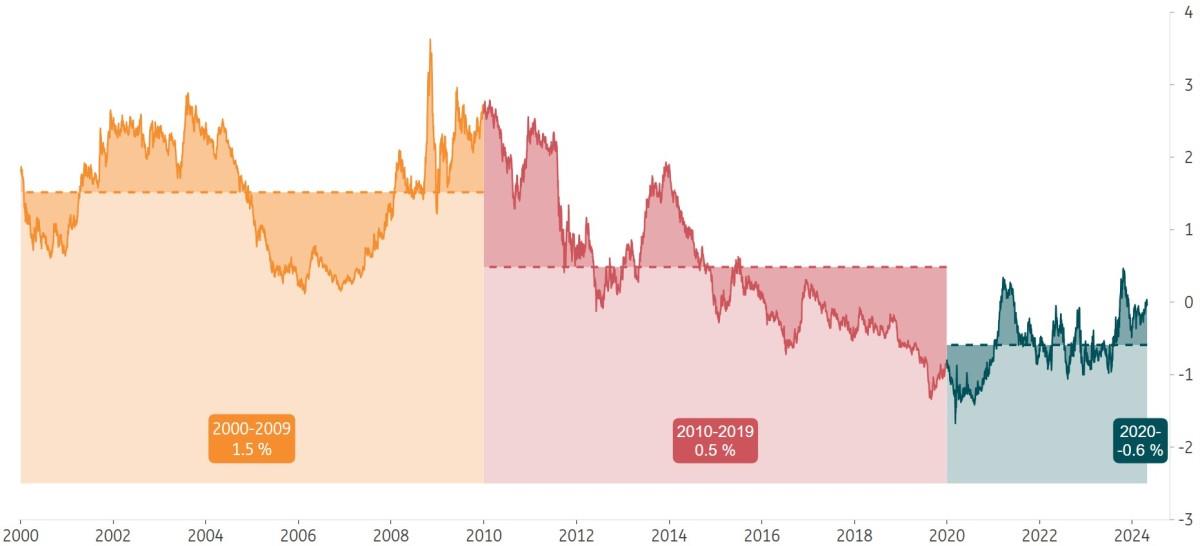

Recent years have seen an unusually low (to an often negative) term premium, post the GFC and then the pandemic. But, if we glance back at the noughties, the term premium then averaged 1.5% on the 10-year yield. The fiscal deficit narrative is a route to a rebuild of the term premium. And it may well be necessary in order to continue to attract enough foreign demand for US bonds.

The 10yr term premium is still only zero. Back in the noughties it averaged 1.5%

The averages per decade are highlighted (%)

The Federal Reserve, Macrobond Wide spreads are helping, but some holders are less sticky

A key supportive factor currently is wide spread US spreads versus other core markets, like eurozone bonds and Japanese government bonds. And the spread over Chinese market rates is also elevated. For the often pivotal Japanese-based investor, the hedge costs back into yen are quite elevated right now, reflecting the size of the interest rate differential. In consequence, buyers of Treasuries from such lower funding rate environments are liable to do so primarily unhedged. With the Federal Reserve minded to keep the funds rate higher for longer, such investors will be receptive to any future risks to the US dollar.

While the issues here range from the size of the fiscal deficit to the lack of compensation in the term premium to a looming and likely pivotal election, we also need to account for geopolitical shocks. Back in 2018, for example, Russia sold virtually all of its Treasuries. This was in the wake of the 2014 Crimean crisis and sanctions, and ominously, ahead of the war against Ukraine. Fast forward, and there are eyes, for example, on Chinese holdings and their stickiness. Also bad actors on a global scale are keen to undermine the US dollar. These are tough elements to anticipate but certainly require monitoring.

Japanese and Chinese investors are the biggest holders of Treasuries. Russians hold virtually none

These data exclude "official holdings", which are sizeable in themselves. The pie expresses proportions of non-official holdings (%)

The US Department of Treasury, Macrobond

There is good news and bad news here.

The good news is that US Treasuries have managed to attract enough foreign investor interest even without the optics of a term premium. The same goes for the success of attracting enough unhedged investor demand. The bad news is that there are vulnerabilities in the other direction. An unabated fiscal deficit can pose a material issue ahead which could prompt the build of a term premium in order to attract enough demand.

The other risk comes from a turn in the US dollar, albeit more likely on the other side of the rate cycle. And there is a circularity here, as any vulnerability with getting enough foreign bond portfolio inflows in to finance the balance of payments deficit poses a vulnerability for the US dollar, too.

MENAFN02052024000222011065ID1108167761

Author:

Chris Turner, Francesco Pesole, Padhraic Garvey, CFA

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images, videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.