China's Got A Fixable Lost-In-Translation Problem

In August of that year, as US subprime debt troubles were starting to bubble up, a bunch of model-driven hedge funds suffered their own“quant quake ,” a phrase now being applied to China.

Drawing such comparisons clearly isn't Beijing's intention. But they come at a moment when many global investors wonder if China is having its own“Lehman moment” amid cratering property and stock values.

Odds are, China isn't, as scores of Asia Times articles have argued in recent months. The market forces in 2007 and 2008 that toppled Lehman Brothers were of a different nature than those plaguing China Evergrande Group or Shanghai trading pits.

Yet the quant crackdown fits with a disturbing pattern that helps explain why foreign investors are so skittish on Chinese markets. It's a reminder of how mixed messaging can cause confusion at a moment when Xi is struggling to revive foreign interest in the stock market - while doing things that scare investors off.

Forty months on, Wall Street is still trying to figure out what's going on with Jack Ma and the much-anticipated Ant Group initial public offering. Despite countless tries, Team Xi never managed to explain that episode - or myriad crackdowns on tech platforms since.

By late 2023, stung by debates about whether China is“uninvestable,” it seemed Team Xi was turning the page. In the last 10 days of last year, though, regulators unveiled plans for a crackdown on the gaming industry.

Though Beijing tried to walk back the news, it was too late as investors feared broader curbs on tech platforms. Tencent alone saw tens of billions of dollars fleeing its shares.

And then just when investors started to dip their toes again in Chinese tech shares, Beijing announced it had amended the State Secrets Law to expand coverage to high-tech industries. The pivot is effective May 1.

Even if this step, which Beijing says supports the research and application of new technologies, is a wise one, confusion and mixed signals abound. Meanwhile, headlines concerning Hong Kong's latest move to implement a new local National Security Law hardly help.

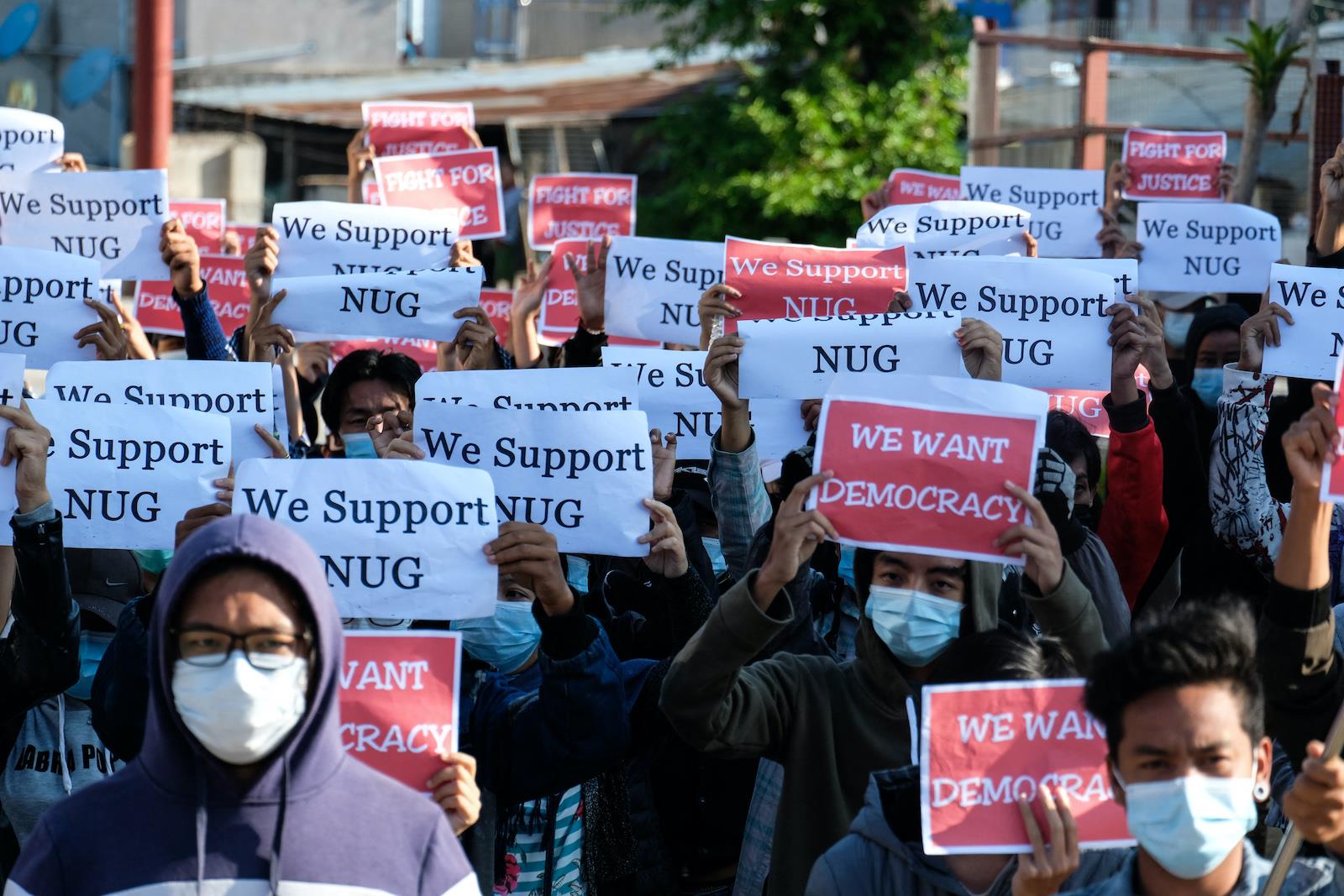

A billboard referring to Beijing's National Security Law for Hong Kong, seen beyond a Chinese national flag held up by a pro-China activist during a rally outside the US Consulate in the city. Photo: Asia Times Files / AFP / Anthony Wallace

The law, foreign investors fear, would go further to remake what was once the globe's freest economy in Beijing's highly controlled image. Its vaguely worded provisions allowing prosecution for offenses from“treason” to“insurrection” to“sabotage” to theft of“state secrets” to“external interference” have investment banks and news organizations in a whirl.

Beijing's quant ban, meanwhile, is triggering the PTSD of all too many investors still trying to make sense of the events of late 2020. The good news is that next week affords Xi and Premier Li Qiang an ideal opportunity to change the narrative and regain reformist momentum.

The annual National People's Congress opens on March 5. Along with setting China's gross domestic product (GDP) target, the NPC is a chance to articulate plans for economic reforms and reboot Xiconomics for the duration of Xi's third term as party leader.

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment