(MENAFN- ING) Renewable power is a key pillar to decarbonising the world economy. We expect decent renewable power capacity growth in Europe and the US in 2024 and beyond. However, it's not happening fast enough because of vulnerable

supply chains, high financing costs, congested grids and slow permitting

In this article Global renewable power deployment: fast but not fast enough Europe and US: a better outlook for solar than wind Persistent challenges, slow progress Elevated interest rates Congested grids and slow permitting processes

supply chain vulnerabilities We need more renewable power than ever

A solar panel farm in the Mojave Desert, USA Global renewable power deployment: fast but not fast enough

With the cost of renewable energy plummeting over the past two decades and renewable energy transitioning to a more mature market, global renewable power capacity additions have been reaching new records for 22 years in a row, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). But the pressure is on to deploy renewable energy even faster. Different parts of the global economy, such as the transportation and industrial sectors, need renewable electricity to decarbonise their operations.

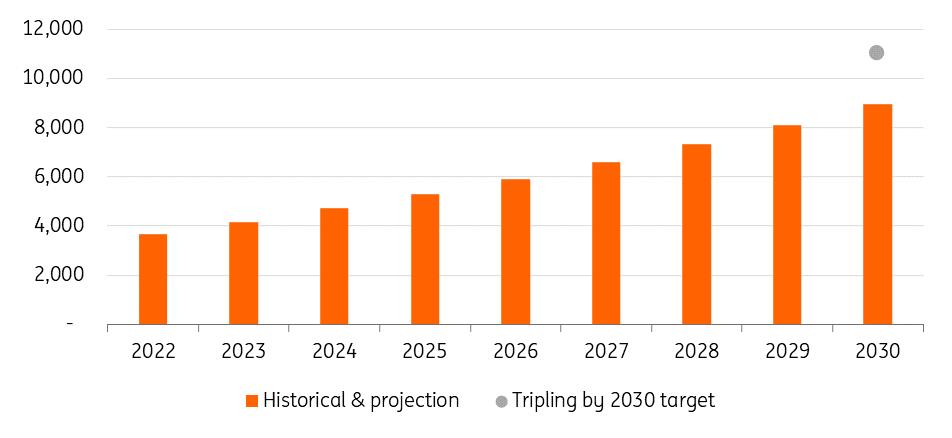

That is why, at last year's COP28, the United Nations' climate conference, governments agreed to triple global renewable power capacity from roughly 3,600 GW in 2022 to over 11,000 GW in 2030. Doing so can help the world reduce a third of the emissions needed to keep global warming within 1.5 degrees Celsius of increase compared to pre-industrial levels.

The IEA estimates that the world is likely to have over 4,700 GW of renewable capacity by the end of 2024, up from just over 4,100 GW in 2023. Under the currently projected policy and market conditions, global renewable capacity will have increased by 2.5 times by 2030.

Efforts fall short of what is needed to triple global renewable power capacity by 2030

Global cumulative renewable power capacity under current policies and economic conditions, in GW

International Energy Agency, ING Research

This projection shows that while tripling renewable power capacity by 2030 is not completely out of reach, current policies and market conditions are not going to get us there. And when breaking down the data, one can also see that much of the growth will come from China thanks to its supply chain domination, substantially higher investment, and lower financing costs. In this article, however, we focus on two other major economies-Europe and the US-analysing the outlook for the renewables market and what is needed to roll out renewable development faster.

Europe and US: a better outlook for solar than wind

We expect a decent renewable power growth rate in the US in 2024. Specifically, the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) expects solar to be the main driver of growth in power generation this year, with its contribution to the power mix rising from 4% in 2023 to 6% in 2024. This contrasts with coal-fired power generation in America, which is forecast to drop by 9% this year because of comparatively higher costs and scheduled coal-fired power plant retirement plans. Wind power, on the other hand, has been more subject to challenges such as higher financing costs and supply chain disruptions and, therefore, will see a short-to-medium cool-down period.

Putting it together, solar and wind power in the US is expected to account for 17% of US electricity generation in 2024, up from 15% in 2023, which indicates a continuously growing renewable power market, albeit at a rather moderate rate. In the medium term, between 2023 and 2028, the US will likely add 340 GW of new renewable capacity, with solar being the main source of growth.

Europe, with a more comprehensive policy framework and a stronger need to transition away structurally from being dependent on Russian natural gas, is further along in solar and wind power deployment. According to Eurostat, in 2022, the EU already generated 15% of its electricity from wind power and 7% from solar power, together accounting for 22% of the generation mix. Solar generation grew the most between 2008 and 2022 and will remain the strongest driver for the 532 GW of anticipated renewable capacity additions between 2023 and 2028. Wind power is still expected to grow in the next few years, but the outlook for growth rates has weakened. To a lesser extent, wind power in Europe is also experiencing concerns over project financial performances and permitting complexities.

Persistent challenges, slow progress

The above-mentioned conditions and projections indicate that Europe and the US are set to fall short of the COP28 goal of tripling renewable power capacity by 2030, but not by much. So the two economies can still turn things around. Below, we detail the challenges facing the renewable power sector in Europe and the US, as well as the advancing, albeit slow, efforts to address them.

Elevated interest rates

Despite falling prices of wind and solar technologies, developers in advanced economies such as Europe and the US have been experiencing higher project development costs in elevated interest rate environments. Relatively more capital-intensive projects, such as wind, have been taking a bigger hit. Moreover, higher interest rates, coupled with inflation and supply chain woes, also mean that projects whose purchasing (customer-end) contracts were structured and signed based on lower interest rates face the challenge of not being able to bring enough revenue. This has indeed led some developers to delay or cancel projects in the hope of renegotiating contract prices. In the US, for instance, more than 10 GW of planned offshore wind capacity has been impacted, risking delays or cancellations, with interest rate-related costs being a major contributor.

Under such circumstances, policy support has become crucial to keep the renewable deployment momentum the US and Europe have experienced so far. And we do have enough reasons to believe that with Europe's RePowerEU policy (combined with other policies in the energy transition and climate space), as well as the US Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), the two regions should still expect continuous growth in the long term.

Congested grids and slow permitting processes

Another challenge facing both the European and US renewable power markets is grid congestion and permitting challenges.

In Europe, renewable developers in many countries have expressed challenges and, hence, negative impacts on project advancement because of complex and lengthy permitting processes. In some countries, such as Greece and Hungary, governments have stopped accepting applications for large-scale power projects. Efforts to change such situations are nevertheless underway. The EU has set a limit of two years allowed for permitting processes. Germany has simplified grid connection requirements for residential systems; the Netherlands is also working on accelerating the permitting procedures for renewable projects.

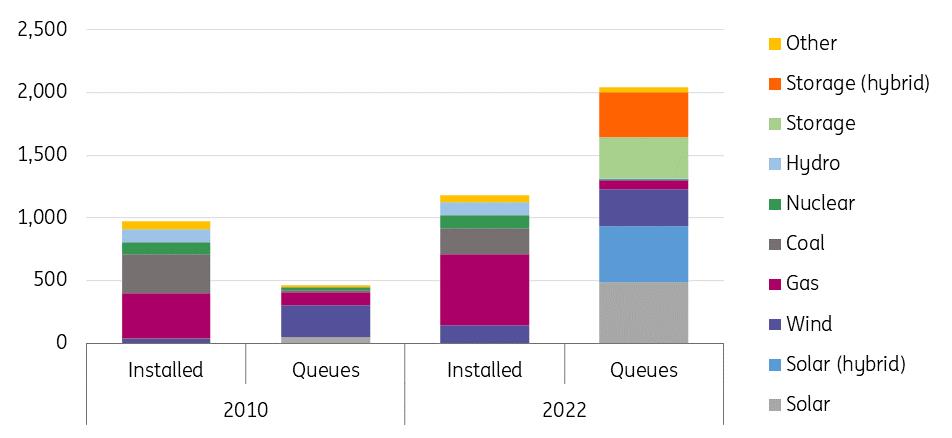

In 2022, more than 2 Terawatts (TW) of US power capacity were waiting to get online, the vast majority of which were solar, wind, and storage projects. The reasons for such congestions, as we have analysed before, include lengthy permitting processes and a lack of experienced government staff to review renewable projects. Remarkably, the 2 TW waiting capacity is higher than the total power capacity of nearly 1.3 TW in the US in 2022. That is to say, if all of the awaiting capacity were to get online today, the US would have more than doubled its power capacity almost exclusively with renewable energy. Recognising the problems, the Biden administration is working to speed up the permitting processes through proposed Federal Energy Regulatory Commission reforms. However, the progress is expected to be slow, given the amount of effort needed to bring visible changes to the current power system.

Renewable power capacity waiting to be connected to the grid has built up in the US over years

Capacity in GW

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, ING Research

For both the US and Europe, there is an urgent need to expand grid transmission capacity to accommodate more planned projects. The IIJA, for example, is allocating funding to build more high-speed transmission lines. Similar efforts are happening in Europe, though in both regions, it will take a while before developers start to see meaningful changes.

And in both economies, developers are increasingly interested in building up battery storage capacity along their renewable projects. In the US, nearly half of the proposed solar capacity and 8% of the proposed wind capacity in the queue are hybrid plants with storage capacity (although the IRA tax credits favouring standalone battery projects could alter this trend). In Europe, there have been government-led auctions of renewable-storage colocation projects (e.g. in Germany) and the rise of hybrid purchase power agreements (which allow a more flexible contract structure for renewable plus storage projects), though the designs of these mechanisms still need improvement.

Supply chain vulnerabilities

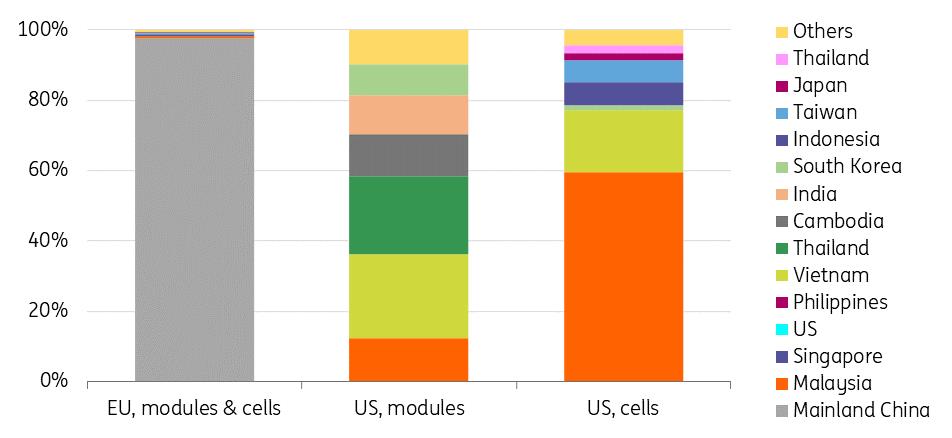

China controls the majority of raw materials and manufacturing capacity needed to build renewable equipment. The EU and the US largely depend on imports of renewable power equipment-particularly in the solar industry. In 2022, the US produced 5 GW of solar PV modules while importing 29 GW of solar PV models. Europe added 41.4 GW of solar capacity in 2022, while only 1.7 GW of wafers, 1.4 GW of cells, and 9.2 GW of modules were manufactured domestically.

In the first half of 2023, 98% of Europe's imports of solar PV modules and cells came from China, making Europe extremely dependent on only one country for its solar power raw materials. Although the US barely imports solar equipment from China because of trade restrictions, most of its imports come from Southeast Asian countries, which could likely be materials being rerouted from China.

EU and US are subject to supply chain vulnerabilities

Solar PV modules and cell imports of the EU and US by origin

Bloomberg New Energy Finance, ING Research

Under such a context, securing supply chains will be a major theme for the renewables industry this decade and beyond. Both Europe and the US are working to enhance supply chain independence. The EU has vowed to become at least 40% independent in net-zero technology manufacturing capacity, while the US has included a series of domestic clean energy supply chain buildup policies in the landmark IRA.

Both regions are expected to develop solid clean-energy supply chains eventually, but it will take a long time and be costly. Before then, project developers around the world can expect additional protective policy measures from the US and the EU to protect their developing supply chains, including carbon border adjustment mechanisms, trade restrictions, import tariffs, etc. From China's side, it is unclear what the policy response will be, and there is a risk that the country might impose countermeasures, further complicating the geopolitics of the global renewables supply chain. These measures may not be beneficial for developers and raw material manufacturers from a global trade perspective, but it is something they will increasingly need to consider and manage.

We need more renewable power than ever

As various sectors accelerate toward electrification, the world needs more renewable power than ever. Significant drops in project costs and scale-ups in installed capacity in the past two decades are evidence that wind and solar power has entered a mature stage of development. However, such progress should not disguise the persistent challenges facing renewables. Faster adoption of renewable power needs comprehensive reforms in power system design, permitting, and labour education, as well as constant policy adjustments, to reflect the current macroeconomic conditions.

MENAFN29012024000222011065ID1107782409

Author:

Coco Zhang, Gerben Hieminga