Freefalling yen a soaring global risk

TOKYO – Could the Japanese yen's 12% decline this year be an even bigger threat to global markets than inflation, Federal Reserve tightening and war in Ukraine?

A month ago, this question might have elicited eye-rolling and guffawing. Now, no one is laughing at the risk of the third-most-traded currency plummeting from the grasp of Tokyo officials notorious for micromanaging exchange rates.

For this, there are two decidedly sober explanations.

First, few events wreck a hedge fund's year faster than a sudden . From the late 1990s to the early 2000s to the 2008-09 global crisis, there are myriad well-documented examples of sharp yen moves devastating markets.

Second, there's something quietly terrifying about the developed world's most indebted nation being unable to hold its own, financially speaking.

The problem, of course, is that the Bank of Japan spent the last 20-plus years flooding world markets with yen. After the 1980s“bubble economy” imploded, the BOJ stabilized things – including a traumatized banking system – by switching yen-printing presses to the“high” setting.

Then came the deflation of the late 1990s. By 2000, the BOJ became the first developed nation ever to cut official interest rates to zero. A year later, it pioneered quantitative easing.

By then, the“yen-carry trade” had become globalization's equivalent of caffeine. Borrowing cheaply in yen and reinvesting funds in higher-yielding assets from Sydney to Sao Paulo to New York became the go-to trade of global finance, particularly among hedge funds.

That is, until the yen does something punters don't foresee.

Here, think 1998 when Russia's default upended yen trades as it killed John Meriwether's Long-Term Capital Management hedge fund. Yen gyrations added fuel to the dot-com crash a couple of years later. In 2008, when the carry trade was more crowded than ever, ended badly again.

There's thus good reason to worry that Japan's government could soon be on the losing side of markets turning on the yen.“The pressure cooker is set to continue for the yen,” warns John Hardy, head of FX strategy at Saxo Bank.

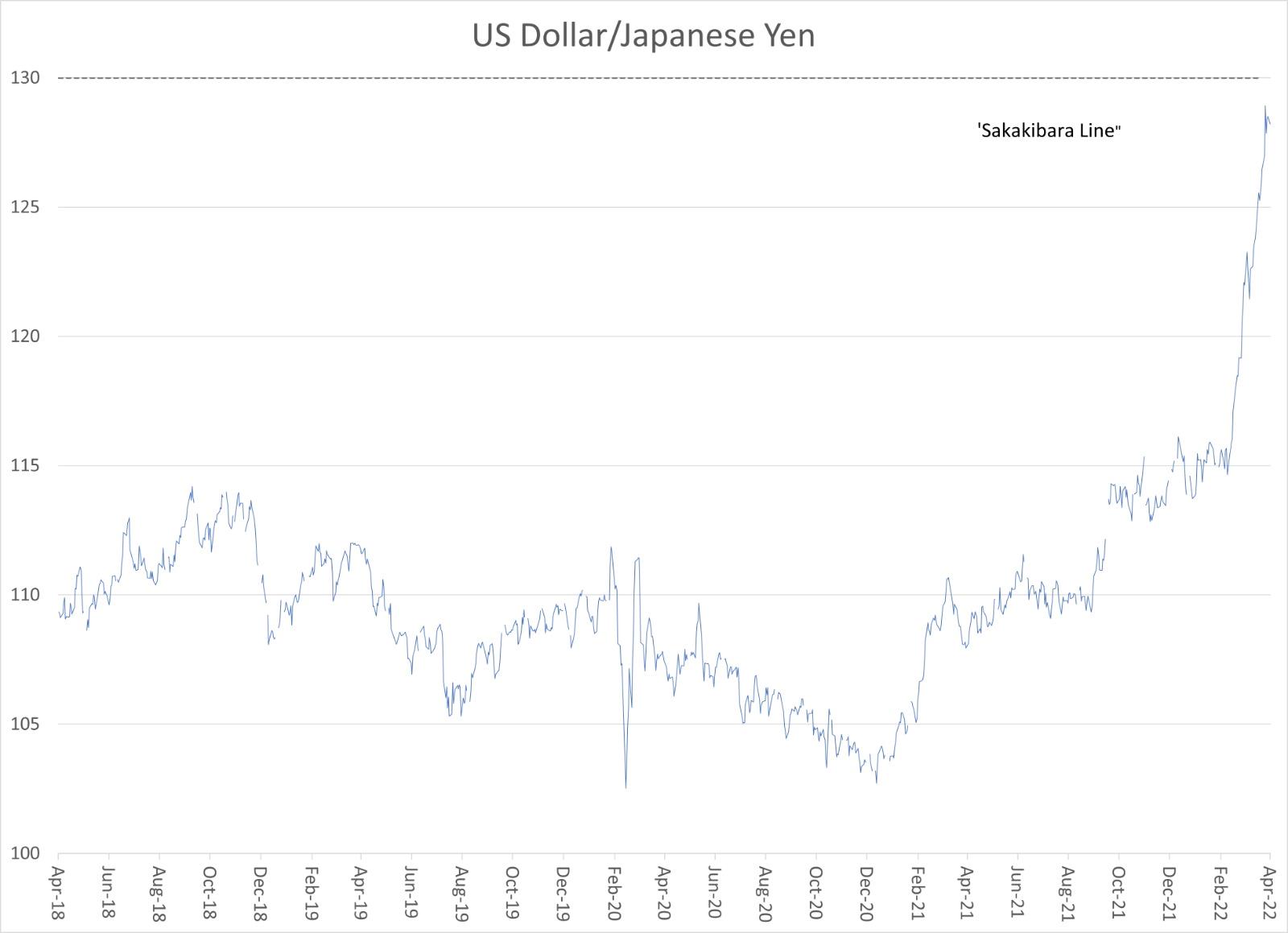

Dollar-yen exchange rates since 2018. The weakening of the Japanese currency this year has been dramatic.

Inflation is one problem. For 20 years now, the BOJ has been struggling to end deflation. That effort got supersized in 2013, when Governor Haruhiko Kuroda took the reins at the BOJ.

His team cornered the government bond market and stocks, too, via exchange-traded funds (ETFs). By 2018, the BOJ's balance sheet topped the size of Japan's entire $5 trillion economy.

Japan is finally getting inflation. In March, consumer prices rose to 1.2% from a year ago. Forecasters expect it to reach 2%, the BOJ's target rate, in the coming months. Trouble is, this is the“bad” kind of inflation: imported price increases via a weak exchange rate. With the yen at 20-year lows, Japanese households and businesses are losing purchasing power.

With Covid-19-related supply-chain disruptions colliding with fallout from Russia's Ukraine invasion, commodity price surges are likely to continue boosting Japanese inflation. And that could cause increased volatility in Japan's massive government bond market.

Tokyo has long kept the peace in bond circles by ensuring upwards of 90% of outstanding Japanese government bonds, or JGBs, are held domestically.

Kuroda's team went even further to hoard debt. Since 2013, there have been countless days when not a single security has traded hands.

Now, the risk is that the awakens from its BOJ-induced slumber. With a debt-to-gross domestic product (GDP) ratio exceeding 250%, any turmoil in yen debt markets could shake the global financial system at the very worst moment.

An accelerated yen drop could have big implications for markets everywhere.

The rising cost of hedging global stability, for example, means the extra returns investors might get from holding US Treasury securities compared to Japanese debt is becoming smaller.

If giant Japanese banks, insurance companies and other institutions use a weaker yen rate as an excuse to shift into Japanese assets, US yields could rise. That includes the $1.6 trillion Government Pension Investment Fund.

In recent weeks, Kuroda's team made it abundantly clear that the late 2021 chatter about“BOJ tapering” was wildly off-base.

Bank of Japan Governor Haruhiko Kuroda. Photo: AFP / Yomiuri Shimbun

More recently, the BOJ has been ramping up liquidity programs. That includes effectively intervening in debt markets to cap 10-year bond rates. The urgency increased as yields tested the 0.25% level, a psychologically important level among debt traders.

“Clearly, we have moved into the stage of heightened surveillance, which normally precedes FX intervention,” says Francesco Pesole, currency strategist at ING Bank.

Japanese Finance Minister Shunichi Suzuki has ratcheted up the rhetoric, warning traders not to test Tokyo's resolve to slow the yen's decline, calling it“bad” for the economy. Currency analyst Lee Hardman at MUFG Bank says such warnings“should at least help to slow the recent fast pace of yen selling.”

Yet Tokyo might find it hard to muster assistance from other industrialized nations. At last week's Group of 20, Suzuki tried to win allies to cooperate on . Instead, Tokyo encountered seeming indifference.

“What we're seeing so far on the yen is driven by fundamentals,” Sanjaya Panth, deputy director of the International Monetary Fund's Asia-Pacific department, told Reuters. The fundamentals in question are driven by a Fed that's tightening and a BOJ in Tokyo veering in the opposite direction.

There's a growing realization, says long-time Japan expert Richard Katz, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Council For Ethics in International Affairs, that a weaker yen“no longer boosts exports as much as in the past.”

One reason: many of electronics and machinery are now less competitive.

Even with the 40% surge in global electronics sales from 2008 to 2020, Katz says,“every one of Japan's top ten electronics hardware manufacturers saw its global sales slump. Japanese companies that used to be able to charge a premium price now have to scramble for sales by offering lower prices. But the size of the necessary price cuts has gotten bigger.”

Another reason: more companies are sending production offshore. Two-thirds of Japanese autos are made overseas these days, Katz says, noting a BOJ study showing that industries with more overseas production get less of an export boost for each 1% depreciation of the yen.

In its study, the BOJ looked at 2,700 different products. Between 2002 and 2010, 86% of products got a boost from a weaker yen. From 2011 to 2019, only 72% of products did. For the other 28%, Katz notes, yen depreciation actually hurt exports because it raises the cost of indispensable imports like energy and raw materials.

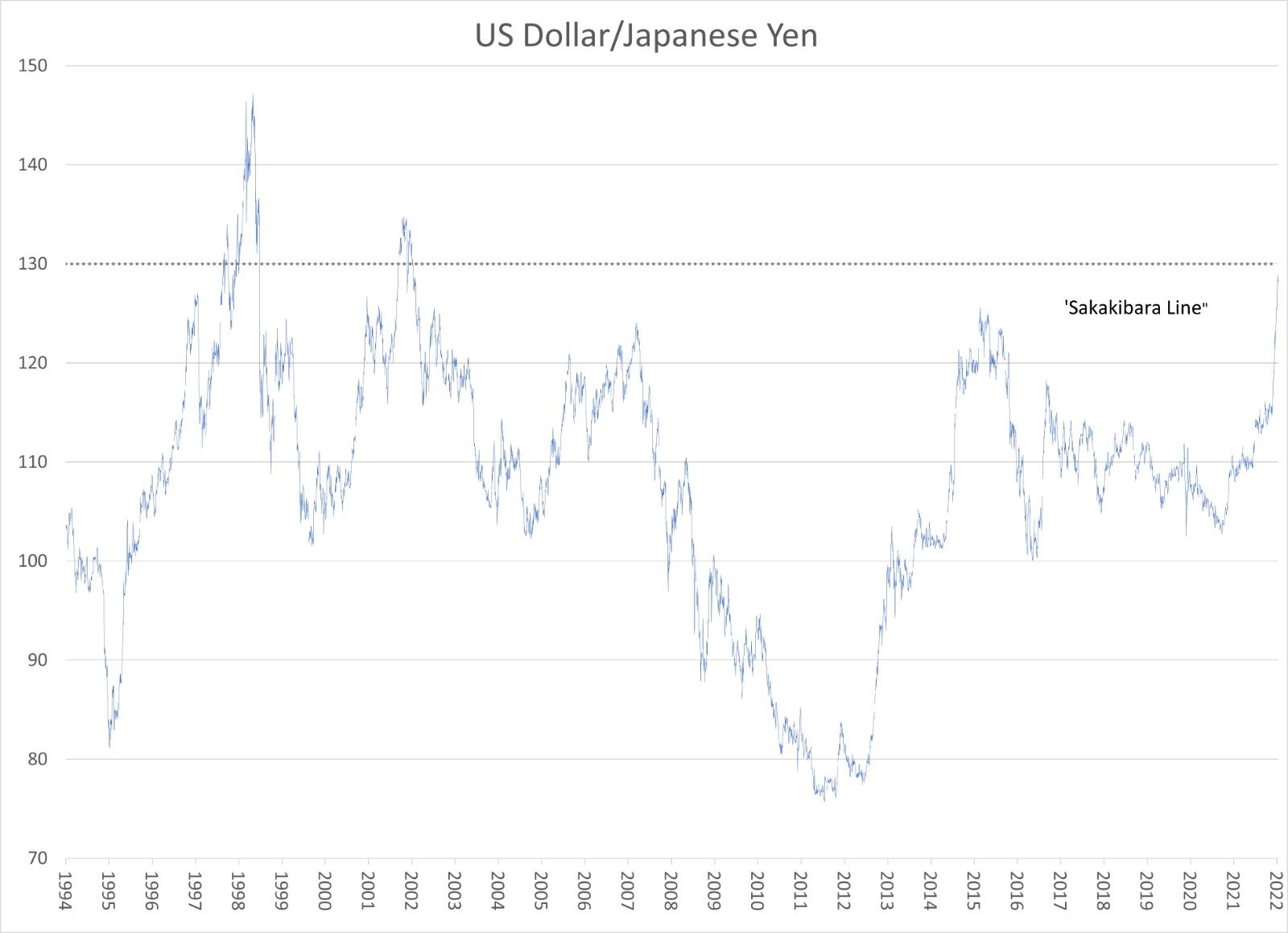

Long-term dollar-yen trends, up to present.

Moreover, even for the companies that still benefited from yen depreciation, the size of the export boost was a lot smaller than ten years earlier.

These days, of course, the G20 and G7 are far more concerned with the . As the biggest trading nation, zig and zags in China's exchange rate are more impactful in the short-to-intermediate term than the yen.

The yen's declines, though, could accelerate toward the 130-to-the-dollar mark, says former Finance Ministry bigwig Eisuke Sakakibara. A breach of 130, from 128 now,“could cause problems,” says the man who led the MOF's currency policies in the late 1990s. (A job Kuroda once had, too.)

If the yen's drop accelerated, Sakakibara says, Tokyo could try its hand at old-school yen-buying intervention. The BOJ also could take steps to withdraw liquidity or even raise some market rates.

For now, yen“depreciation pressure can continue,” says Goldman Sachs Group strategist Zach Pandl. Yet, he adds, the yen's“topside” will“eventually be contained by intervention.”

But when? Adds strategist Joseph Capurso at Commonwealth Bank of Australia:“We don't know what level of dollar-yen is the line in the sand.”

Regardless, Tohru Sasaki, head of Japan Market Research at JPMorgan Chase Bank. Sasaki thinks the BOJ“has to do something to slow the pace of the yen's depreciation.”

That may include Tokyo selling off some of its .

Kishida would prefer not to comment on the yen. Picture: Agencies

That response could become more acute either as markets demand action or the politics turn on Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida.

His most recent take on the yen was to say:“I will refrain from commenting on the level of exchange rates, but their stability is important and I think rapid fluctuations are undesirable.”

Judging from how yen fluctuations tend to reverberate through world markets, investors probably couldn't agree more. If Japan's system can't hold its own in the year ahead, the globe is in for some rough times.

Follow William Pesek on Twitter at @WilliamPesek

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment