(MENAFN- USA Art News)

“It can be said that every Black person in this country has been impacted by the Great Migration,” said Ryan Dennis, chief curator of the Mississippi Museum of Art , referring to the exodus of more than 6 million African Americans from the Deep South to the North, Midwest, and West Coast, in search of opportunity and agency, from the beginning of the 20th century into the 1970s. The Great Migration touched upon every facet of American life, notably in the arts, and transformed cities and towns across the nation.

Together with Jessica Bell Brown, a curator at the Baltimore Museum of Art , Dennis has commissioned 12 intergenerational Black artists to make new work delving into this major historical and cultural shift through a personal lens for the exhibition“A Movement in Every Direction: Legacies of the Great Migration,” which opens at the MMA on April 9 before traveling to the BMA in October.

Over the course of lengthy conversations on Zoom and over the phone throughout 2020, with the 12 selected artists—Mark Bradford , Akea Brionne, Zoë Charlton, Larry W. Cook, Torkwase Dyson, Theaster Gates, Allison Janae Hamilton, Leslie Hewitt, Steffani Jemison, Robert Pruitt , Jamea Richmond-Edwards , and Carrie Mae Weems—the curators asked,“What's your connection to the South? Where are your people from?” Brown recalled.

As two Black women from the South—Brown is originally from Macon, Georgia, and Dennis was born in Houston and raised in San Antonio—the curators felt an intimate connection to the ground covered in these conversations.“Jess and I were really stunned and in deep gratitude,” Dennis said recently,“that folks would want to embark on such a personal exploration with us for a show like this, which is not typically done in contemporary art. Deeply familial kind of ties are just not something that is talked about.”

Five of the artists, including Weems, Dyson, and Brionne, have direct links to Mississippi. Now based in Chicago, Gates grew up in Humphreys Country, Mississippi, and his large-scale sculptural piece, The Double Wide, is modeled on an oversize trailer owned by his uncle that doubled as a candy store and juke joint. It is installed with objects and ephemera evocative of Gates's childhood and features a soundtrack of icons like B.B. King and Muddy Waters, whose Mississippi-born blues influenced music nationwide.

For Richmond-Edwards, the call from the curators came serendipitously. The artist was already in the thick of tracing her ancestry, just for her own edification, not for her artistic practice. Born and raised in Detroit, she had attended Jackson State University, only to learn more recently from her genealogist that some of her family had migrated from Virginia to that region in Mississippi before heading northwards, ultimately to Michigan.“I already had ties to Mississippi unknowingly,” said Richmond-Edwards, whose research revealed the recurrence of water disasters, including the great flooding of the Mississippi River in 1927, precipitated her family's many movements during the 20th century.

For her 8-by-15-foot painting This Water Runs Deep, Richmond-Edwards places portraits of herself and her immediate family members in a boat encircled by a dazzling water serpent.“I decided to use the water as allegory to our resilience,” she said.“Despite all the political terror and elemental terror, you see my family unbothered by the water and we're actually one with the dragon. My family story is epic and I didn't want it to be rooted in any sort of subjugated way.”

Bradford, born and based in Los Angeles, approached the project from a place of not knowing much about his ancestry—only that his mother's people were from Coatesville, Pennsylvania, about an hour west of Philadelphia.“Mark talks about his family on his mother's side as these entrepreneurial spirits, needing to move and willing to take the risk to see the opportunity,” Dennis said.

In his exhibition research, Bradford found a 1913 advertisement in a magazine published by the NAACP seeking 500 families to settle a“colony” called Blackdom in New Mexico that would be free of Jim Crow laws (and was short-lived). The text became the template for the 60 individually painted and oxidized panels arranged in a massive grid that make up his commission, 500.“It's a beautiful metaphor for that quest for agency and empowerment that shows up in these surfaces as a legacy he's claiming for himself and his family,” Brown said.

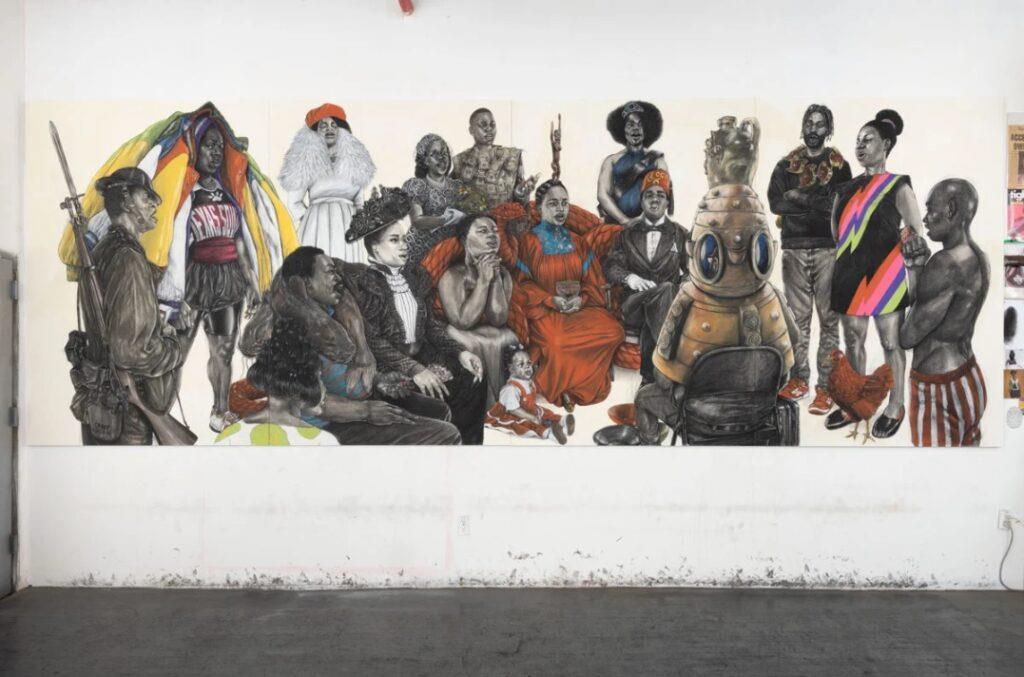

Robert Pruitt, A Song for Travelers (detail), 2022.

For his work, Pruitt, who was born in Houston and lived there until moving to New York in 2016, considers Black communities that have never left the South.“I think our popular understanding of the Great Migration is about escape,” he said,“like people running away in the night to get away from the structure of the South. To me, they're also leaving something very beautiful and nurturing that created who we are.”

In his mural-size charcoal, conté, and pastel drawing titled A Song for Travelers, 15 people gather around and sing to a central figure wearing a headdress with a suitcase by his side. The composition is based on a photo of a family reunion from before Pruitt was born that he found at his mother's house in Houston. The varying dress and styles of the figures are pulled from images dating from 1917 to the present that the artist culled from various archives around Houston. Modeling the traveler on himself, the piece becomes a self-portrait in some ways, Pruitt said, and more broadly represents the long history of communities that have wrapped arms around migrants.

When the curators initially reached out to Charlton, she hadn't considered that her family—largely based in Tallahassee, Florida—participated in the Great Migration.“I started thinking about the number of people in my family that had been a part of the military during the times of the Great Migration and thought that is a place that I can add to the conversation,” said Charlton, who was born on an Air Force base in Fort Walton Beach, Florida, and lived a variety of places throughout the U.S. and abroad while her father was in the service.

Zoë Charlton, Permanent Change of Station, 2022.

Her installation Permanent Change of Station includes a large-scale graphite drawing of an imagined landscape in Vietnam, where her father fought and her uncle died, and a life-size pop-up construction that unfolds in front of the drawing, almost like a children's storybook. Rows of collaged flora and fauna on wooden supports surround a three-dimensional mock-up of Charlton's grandmother's home in Tallahassee—a commonplace type of house in the Florida panhandle that the artist thinks of as“a marker of stability in my own family and a marker of a kind of Black Southern-hood.”

The commission for“A Movement in Every Direction” gave Charlton the space and time to talk with family members about why they joined the military.“It was really about the opportunity that it posed for them, to have economic and cultural and social mobility,” Charlton said.“The military was a space of aspiration for Black folks. I credit my experience of the military to why I am the way I am.”

MENAFN13042022005694012507ID1104015508

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images, videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.