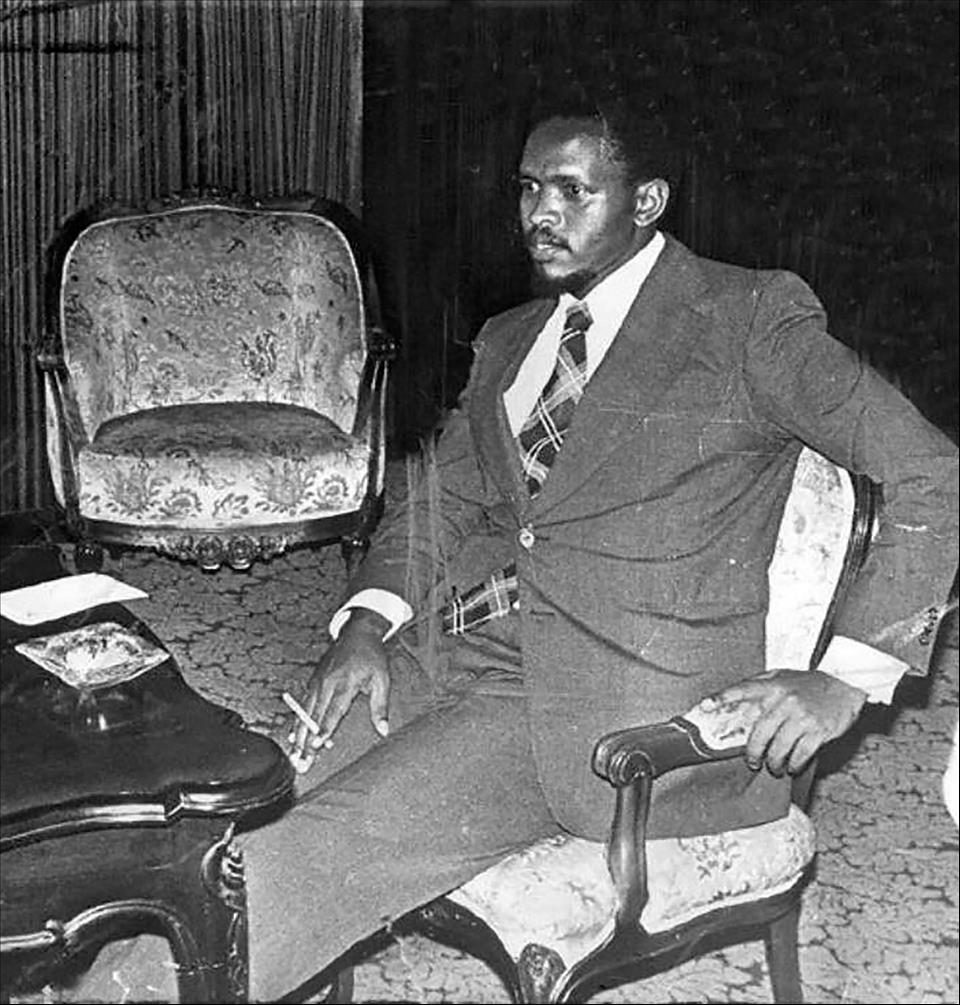

Steve Biko, The South African Struggle Hero Who Was Prepared To Sacrifice His Life For Black Liberation

Steve Biko 's death on 12 September 1977 generated arguably the most significant hagiography and iconography to come out of the struggle against apartheid. Artist Paul Stopforth was among the first to respond critically to the murder, producing a collection titled the Biko Series .

Stopforth reworked the forensic photographs from Biko's autopsy to show not just the brutality to which Biko was subjected by his killers but, significantly, the manner in which they inadvertently made the killing look like a crucifixion.

In his book, No One To Blame? , about deaths in police custody in South Africa, human rights lawyer George Bizos titled the chapter on Biko“The passion of Steve Biko”. Bizos was not the only one to see Biko's death in terms of Christian notions of sacrifice. Reacting to the death of her husband, Ntsiki Biko said :

Biographer Lindy Wilson also took a scriptural approach to Biko's life. Remarking on Biko's birth in 1946 and on his name, Wilson wrote :

The biblical Stephen accused Jews of being false to their faith by failing to acknowledge Jesus of Nazareth as the Messiah. The Jews stoned him to death.

Biko grew up in a Christian family and, despite his later scepticism towards the church, retained the religious influences of his upbringing. When the government banished him in 1973 to his home district of King William's Town, effectively forcing him to abandon his studies at the University of Natal Medical School, he assuaged his mother's fears by asking her about the purpose of Jesus's mission on earth. When she answered:“To save the oppressed”, Biko said :“I too have a mission”.

According to Wilson, it was then that Biko's mother realised that

In fact, Biko's religious casting of his own activism was a key reason for his charisma and public standing. This casting cemented Biko's faith in the correctness of his cause. This faith, coupled with a fierce intelligence, gave Biko a sense of confidence that unnerved the apartheid security police. They saw him as a man out of place, a native who did not know his place.

As Bizos said ,

Biko drew from his understanding of Christian ideas about sacrifice and from his upbringing in an African household a notion of dignity that guided his politics and shaped his philosophy. Father Aelred Stubbs, an Anglican monk who became one of Biko's closest friends, remarked on Biko's profound sense of dignity:

It is not that Biko lacked fear. He had a keen survival instinct. But he valued dignity. He preferred death before dishonour.

The power of Biko's intellect and the fact that he, unlike Nelson Mandela, never took up arms against apartheid demand that we take seriously his pronouncements. This means that we must remember him not simply as the charismatic leader who gave his life for freedom but as the embodiment of a much older Greek and Christian concept of martyrdom, namely the idea of a martyr as s/he who bears witness. Biko married reason with proselytising in ways that made him an excellent organiser and a powerful witness.

He understood the importance of organising and the need for faith in action. As he told a group of church leaders in 1972,

The reminder was as provocative as it was timely. Biko and his fellow activists in the black consciousness movement effectively turned the popular saying“God helps those who help themselves” into the more politically charged slogan

As a newspaper columnist, Biko used his writings to define and publicise his philosophy of black consciousness. He and the black consciousness movement challenged negative associations with blackness by asserting that“Black is beautiful”.

Biko and his movement turned the term“black” into a powerful tool for the assertion of their right to dignity. By emphasising black beauty and by insisting that blacks take the task of liberation into their own hands, Biko and his colleagues inaugurated a form of politics that helped revive a moribund liberation movement, mainly the African National Congress.

When thousands of young South Africans left for exile in the wake of the 1976 Soweto uprisings and after Biko's murder, many of them joined the ANC . They brought with them a philosophy that inspired the ANC, still stuck in staid Marxist debates and beholden to Cold War loyalties, to emerge by the 1980s as South Africa's premier resistance organisation. These activists' insistence on black initiative pushed the ANC to refine its own philosophy of non-racialism.

It is no coincidence that the ANC first opened its membership to non-Africans in 1969 and elected its first white executive member in 1985, both milestones tied to significant dates in the formal emergence of black consciousness in South Africa. Even the jailed Mandela was moved to a grudging respect of Biko's movement, lauding its

The quest for a true humanityBiko's most eloquent philosophical statement was the essay“Black consciousness and the quest for a true humanity”. Published in 1973 in a volume about South African perspectives on black theology, the school of thought developed by American theologian James H. Cone , the essay sought to relate Cone's ideas to South Africa. Biko argued that racism in South Africa grew out of economic exploitation.

Out of this had developed a culture that made racism both individual and institutional. Biko rejected the idea that the solution to South Africa's fundamental problem, meaning apartheid, lay in a nonracial coalition between black and white.

He said black South Africans could not look to their white counterparts for their freedom.

That is why, he continued, the South African Students Organisation (Saso) that he led adopted the slogan

Defining his philosophy, Biko said :

Dying for Freedom is published by Polity .

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment