(MENAFN- Asia Times)

In explaining the reasons for Russia's unexpected military weakness in Ukraine, few have expressed it better than The Economist. The magazine noted“the incurable inadequacy of despotic power” and“the cheating, bribery and peculation” that are“characteristic of the entire administration.”

Peculation means embezzlement. It's a word rarely used nowadays; these words were in fact published by The Economist in October 1854 , when Russia was in the process of losing the Crimean War.

But they might just as easily be about Russia today, under Vladimir Putin, and about the mess of its invasion of its far smaller neighbor. Rarely have the pernicious effects of authoritarianism and endemic corruption been so vividly on display.

Indeed Ukraine's National Agency on Corruption Prevention has cheekily thanked Russian officials for making it“much easier to defend democratic Ukraine” by embezzling“what should have gone to the needs of the army.”

How corrupt is Russia?

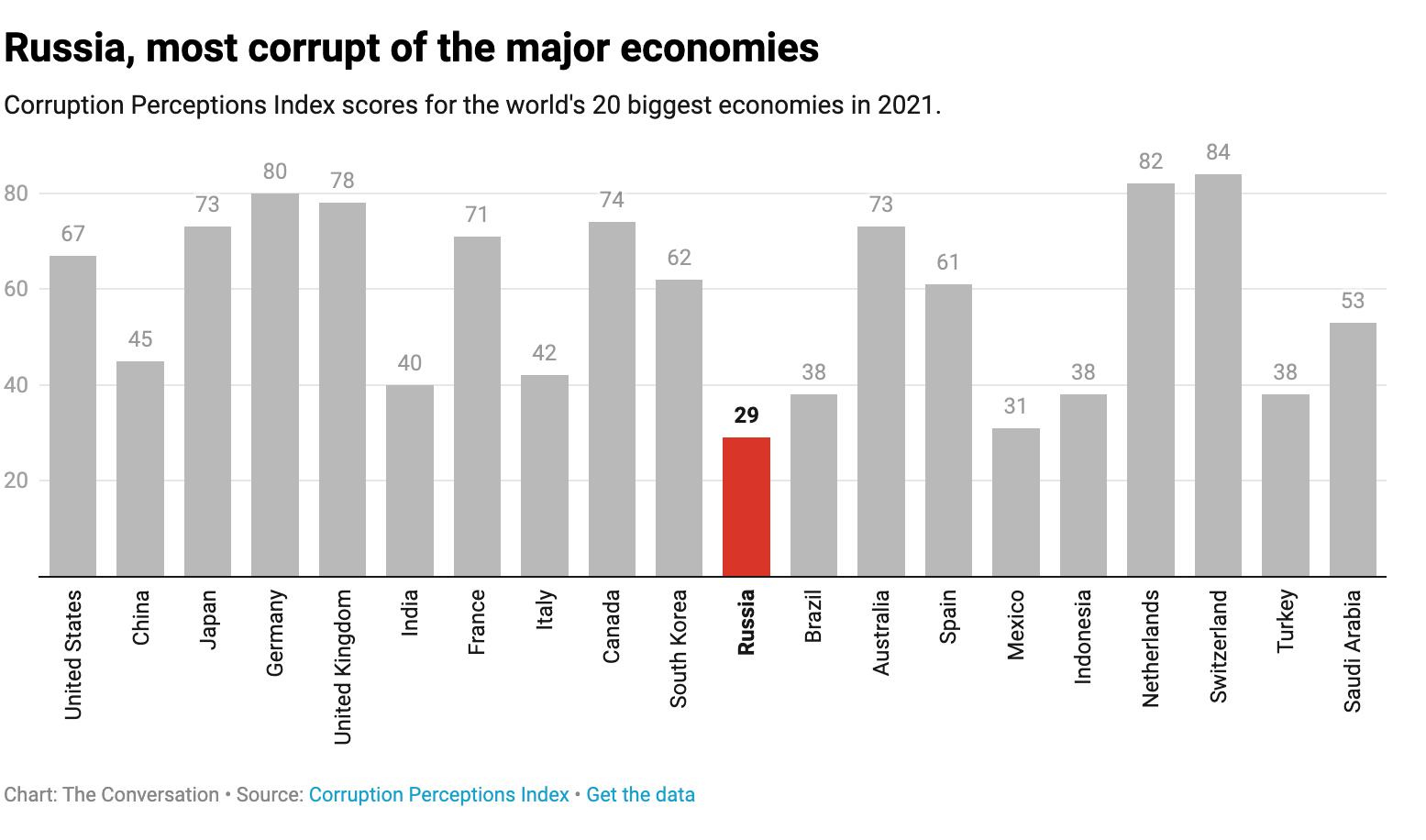

Of the world's 20 major economies, Russia rates the worst on corruption.

In 2021, the respected Corruption Perceptions Index compiled by anti-corruption body Transparency International scored Russia 29/100, alongside Liberia, Mali and Angola. This made it the 44th most corrupt nation on the index. (South Sudan was most corrupt, scoring 11/100, and Denmark the least corrupt, with 88/100.)

To be fair, the score isn't much better for Ukraine, which went through a similar post-Soviet privatization process that delivered immense wealth to a few oligarchs. Its 2021 corruption score was 32/100.

But President Volodymyr Zelensky has made tackling corruption a central policy, and Ukraine is improving on the index – unlike Russia. Ukraine also has some clear advantages for further improvements.

The US organization Freedom House gives Ukraine a democracy score of 39.3%, compared with 5.4% for Russia. Transparency International rates Ukraine's democratic processes as“generally free and fair.” It considers efforts in recent years to tackle corruption as slow and flawed, but nonetheless genuine and substantive.

Russia's rule of thieves

Putin's Russia, on the hand, is described by Transparency International as a kleptocracy – a government of thieves. Putin himself is estimated to have accrued a fortune of US$200 billion , making him (unofficially) the world's second-richest man, after Elon Musk.

Putin's wealth accumulation methods are relatively straightforward. According to Bill Browder, a fund manager specializing in Russian markets, having Mikhail Khodorkovsky – then Russia's richest man – sent to prison in 2005 proved particularly fruitful:

Much of Putin's fortune is squirreled away in foreign bank accounts and investments, as revealed by the Pandora Papers . But he also enjoys material comforts such as a palace on the Black Sea reputed to have cost about US$1 billion – paid for in part out of a government program meant to improve health care .

Putin's palace is said to contain a swimming pool, saunas, Turkish baths, reading room, music lounge, hookah bar, cinema, wine cellar, casino, a dozen guest bedrooms and a 260 square-meter master bedroom. Photo: Photo: Wikimedia Commons , CC BY

Stealing from military budgets

Money supposed to be for Russia's military capability has also been plundered. For example, defense minister Sergei Shoigu lives in an $18 million mansion – not bad for someone supposedly on a government minister's salary.

A typical swindle has been to award contracts to companies owned by cronies, who then provide shoddy products and pocket huge profits. Food and housing in the Russian military is said to be worse than being in prison . Russian soldiers sent to invade Ukraine have been given rations years out of date .

This has created a“Potemkin military” – all show and little substance – according to Andrey Kozyrev , Russia's foreign minister from 1990 to 1996:

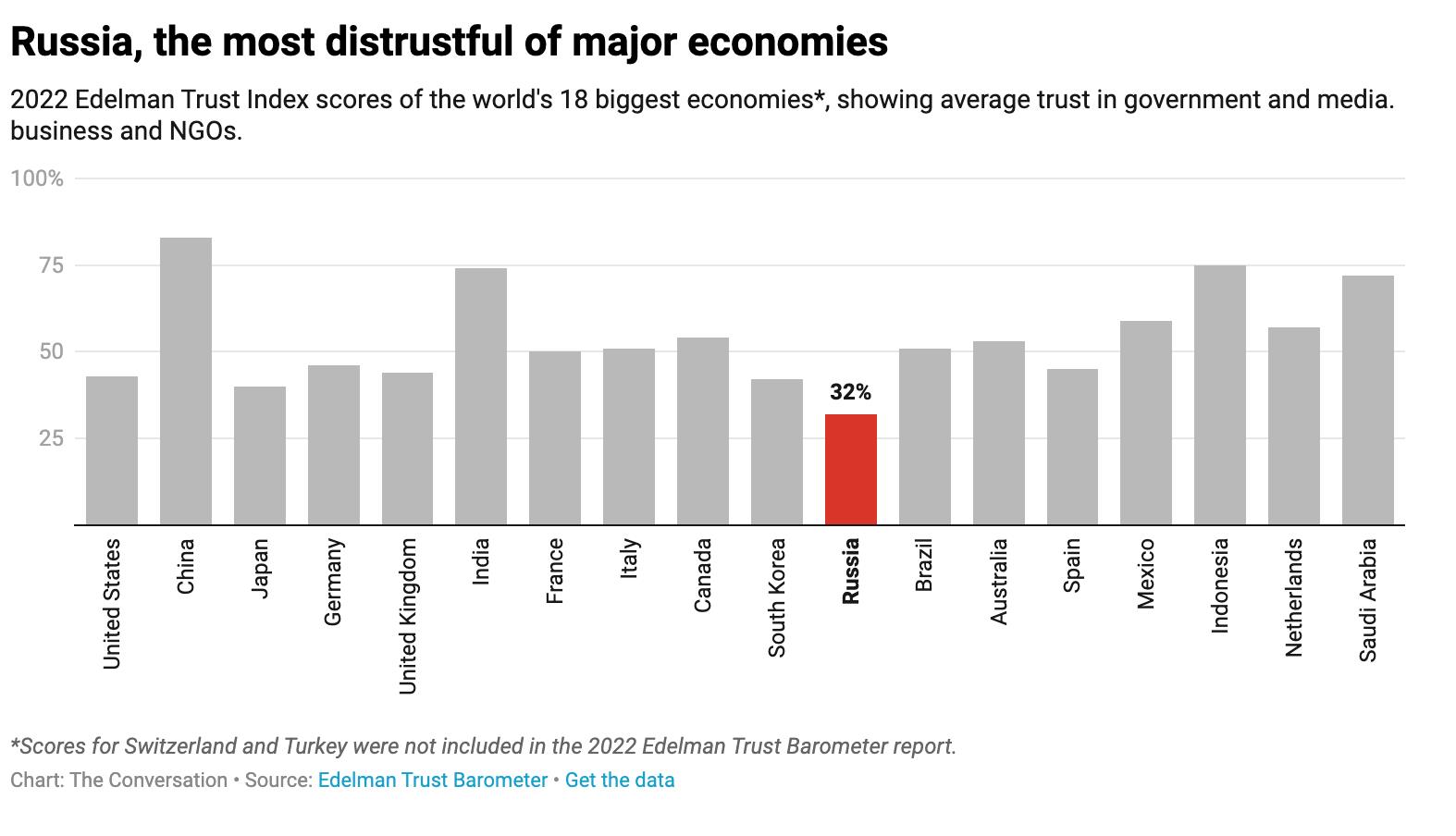

Social distrust runs deep

It should be no surprise, therefore, that Russia is a deeply distrustful society. This has been measured by global surveys such as Lloyd's Register Foundation World Risk Poll and the Edelman Trust Barometer .

This distrust has been a hallmark of the Russian military's performance in Ukraine.

Western military organizations emphasize empowering individual units to show initiative when plans go wrong. In marked contrast, the Russian military structure, like the state, is based on command and control, with little faith or trust in troops.

In particular, Russia's conscription-dependent army lacks non-commissioned officers. These senior enlisted personnel train and supervise troops, and often take over leadership of smaller units in wartime.

This helps explain the high number of senior Russian generals killed on the front line in Ukraine – 12 at last count. Typically, generals manage battlefields from a safe distance. But, as a recent report from The Economist has noted:

And, also, to put themselves within range of Ukrainian snipers and missiles.

This war, which the Russians expected would be over in days, has just entered its fourth month. It's possible the Russian military can learn from its strategic and logistical blunders and still win the battle for the Donbas area.

But, unlike the many Russian officers who are now gone, general corruption and general distrust remain on the battlefield.

Tony Ward is a fellow in historical studies at The University of Melbourne . This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article .

MENAFN27052022000159011032ID1104280067

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images, videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.