(MENAFN- Asia Times) More than 17 years after he died in agony aboard a Garuda airlines flight bound for Amsterdam, Indonesian human rights activists are fighting an uphill battle to keep open the bizarre 2004 poisoning case of military critic Munir Said Thalib and the puzzling conspiracy that lay behind his murder.

The activists want Indonesia's Human Rights Commission to declare the case a grave human rights violation, thereby ensuring that the 18-year statute of limitations prescribed in the Criminal Code is not allowed to lapse in September next year.

“We know it's pretty hopeless,” says one activist, who has tracked the case from its outset and still feels a strong sense of injustice.“But we have to do something to keep the case alive, even if active investigations ceased a long time ago.”

The campaigners appear to have been joined by some unlikely allies. Social media have recently been alive with renewed attacks on A M Hendropriyono, 75, then chief of the State Intelligence Agency (BIN), which was widely suspected of having a hand in Munir's death.

But that may be partly aimed at blunting Hendropriyono's influence in pushing for his son-in-law, Army Chief of Staff Andika Perkasa, to replace armed forces (TNI) commander Air Chief Marshal Hadi Tjahjanto when he retires in November.

President Joko Widodo will have to choose between Perkasa, 56, and Navy Chief of Staff Admiral Yudo Margono, 55, although the latter may have the inside running because it is nominally the navy's turn to take the helm under the three-service rotation system introduced in the early 2000s.

The 39-year-old Munir was on his way to the Netherlands to study for a master's degree in international law and human rights and, despite being a thorn in the side of the military for its long record of human rights abuses, appeared to pose few obvious political problems so far from home.

Some activists believe the slightly-built lawyer was the victim of a personal vendetta for being the first to reveal the role of the Indonesian Special Forces (Kopassus) in the kidnapping and disappearance of pro-democracy activists during the final months of president Suharto's 32-year rule.

Others say that in a country known for its conspiracy theories there may have been suspicions that Munir was passing documents or otherwise communicating with the International Criminal Court (ICC) at The Hague, something that had in fact been discussed in human rights circles.

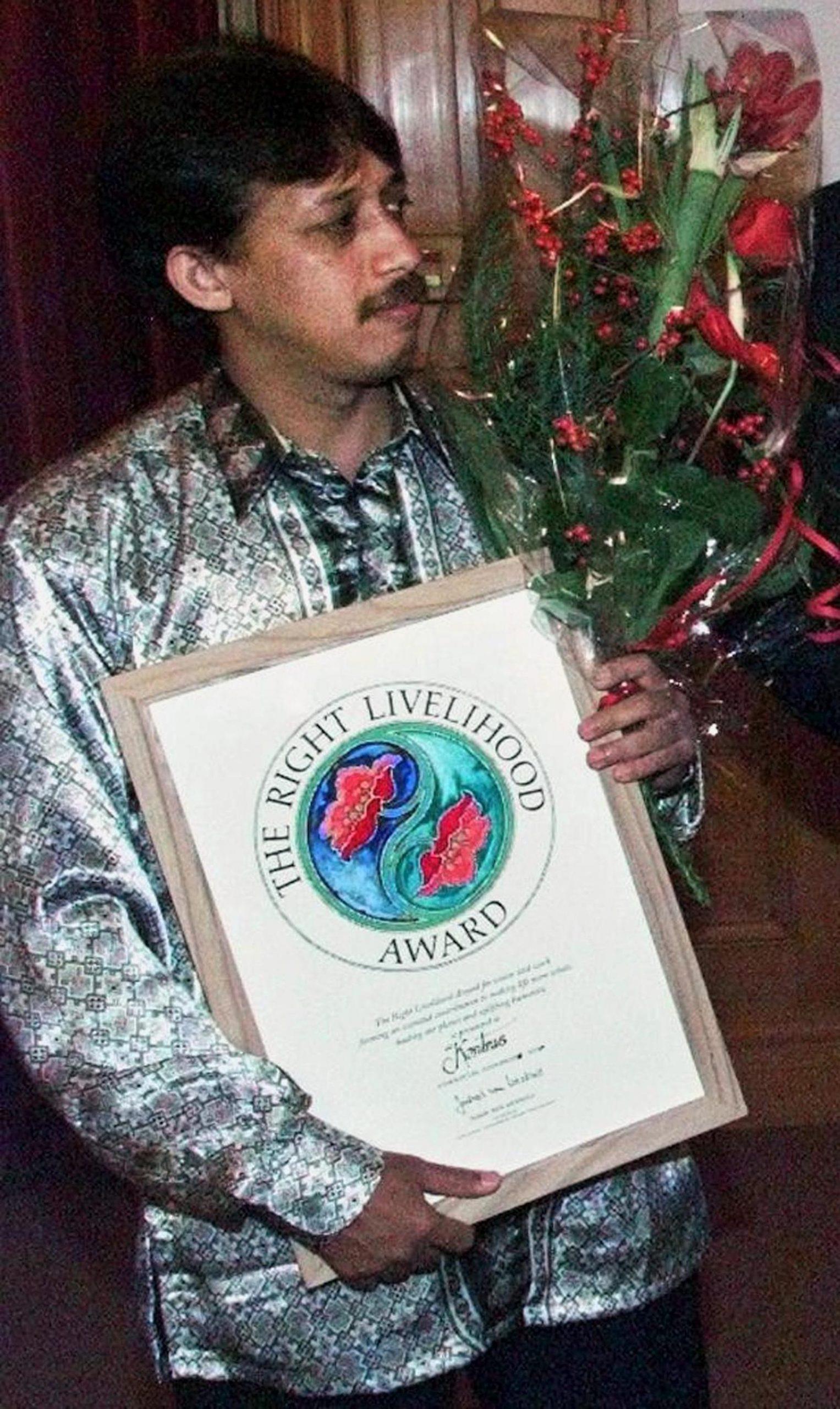

Photo dated December 8, 2000, shows leading Indonesian human rights campaigner Munir Said Thalib standing with the Right Livelihood Award during the presentation ceremony in Stockholm. Photo: AFP / EPA / PRESSENS BILD / HENRIK MONTGOMERY / SCANPIX SWEDEN

Mysterious Pollycarpus Priyanto, 59, the off-duty Garuda pilot accused of administering an arsenic-laced orange juice to Munir during a stopover in Singapore, took that secret with him to the grave when he died last December after a 16-day battle with coronavirus.

He had been convicted and sentenced to 14 years imprisonment in 2005, but a year later the Supreme Court overturned the verdict, citing a lack of evidence. In 2007, the conviction was reinstated and his jail term extended to 20 years, only for it to be reduced to 14 years in 2013.

Garuda chief executive Indra Setiawan was given a year's prison term for agreeing to a BIN request to assign Priyanto as an aviation security officer on Munir's flight, a strange duty for a pilot who had previously been due to fly to Beijing.

Paroled in 2014, Priyanto never explained the 41 calls he made at the time to the cell phone of retired general Muchdi Purwopranjono – Hendropriyono's deputy and a former close associate of Prabowo – who was acquitted in 2008 of masterminding the crime.

Purwopranjono, now 72, had served briefly as special forces commander in the months leading up to Suharto's downfall in May 1998 but was dismissed at the same time Prabowo was cashiered for human rights violations and insubordination.

Several key witnesses retracted their testimony during Purwonpranjono's subsequent trial including a former aide who was subsequently moved from his post at the Indonesian embassy in Pakistan to an even more distant assignment in war-torn Afghanistan. He is now a religious devotee.

Then attorney-general Abdul Rahman Saleh could only gesture helplessly when he told this writer in 2006 that although prosecutors were suspicious of the connection between Priyanto and BIN, there was nothing that could lead to a successful prosecution.

Palace sources claimed Yudhoyono was“frustrated” over the lack of progress in the police investigation and“skeptical” about the grounds for the initial acquittal of Priyanto, whose offer to let Thalib sit in his business class seat had always invited suspicion.

The police would normally be well-equipped to handle the Munir investigation, but its often testy relationship with the military and the influence of the shadowy figures behind the murder have proved to be insurmountable obstacles.

In 2016, the State Secretariat confessed to having“lost” a secret report, prepared for Yudhoyono in 2005, which reportedly named those suspected of being involved in the conspiracy and which could have been used as a basis for re-opening the investigation.

Experienced investigators say that without a record of the phone exchanges, police would have to build a“consequence chart,” determining when the calls were made and then using such evidence as credit card and sales records to determine how Priyanto reacted each time.

In that way, they say, it should have been possible to establish patterns and assemble a chain of circumstantial evidence that pointed to only one possible conclusion: that the pilot was reacting to instructions.

During Priyanto's lower court trial, Munir's widow, Suciwati, openly accused Purwonpranjono of ordering her husband's death. In their verdict, the judges said the phone calls convinced them“an understanding had been reached over the elimination of Munir's life.”

Purwonpranjono claimed he only had his phone at night and that it could have been used by numerous people, but he persistently refused to be questioned by police – a seeming immunity not available to ordinary Indonesians implicated in a crime.

In previous cases involving members of the Indonesian military, prosecutors and judges demonstrated either an inept grasp of humanitarian law or a lack of courage in making the charges stick, particularly against officers charged with crimes against humanity in East Timor in 1999.

MENAFN17092021000159011032ID1102814042

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images, videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.