(MENAFN- Asia Times)

Throughout the 2010s, many people – including myself – treated it as a truism that manufacturing industries have faster productivity growth than service industries.

Historically that was true, and the reason wasn't hard to grasp – machines improve faster than human beings do, so industries that depended on better machines naturally tended to advance faster than labor-intensive service industries.

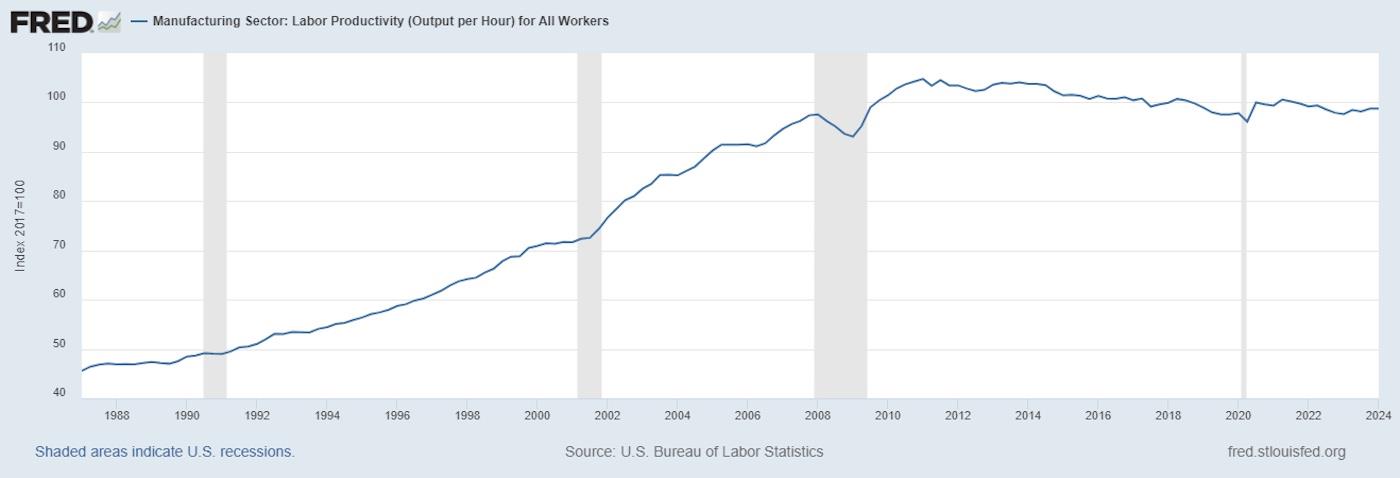

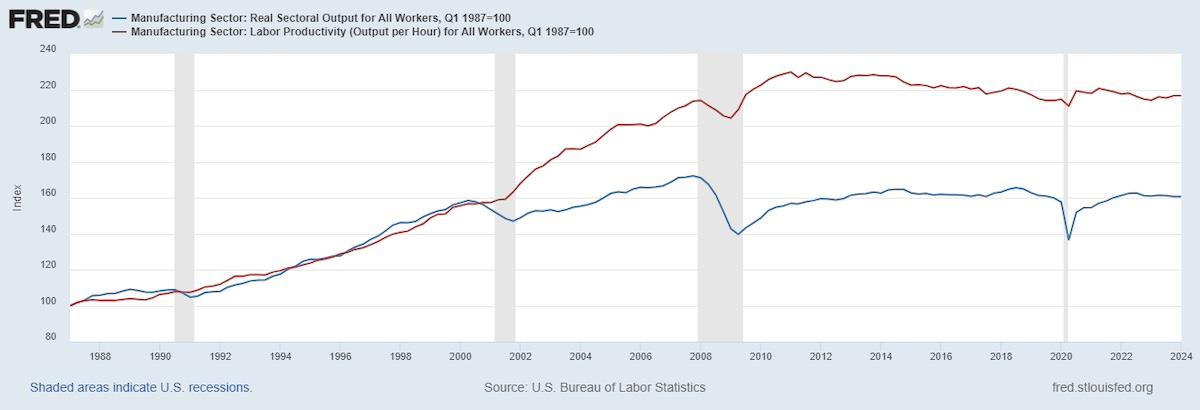

But this particular piece of conventional wisdom stopped being true over a decade ago. In 2011, manufacturing productivity in the US hit a ceiling, and has actually declined in the years since:

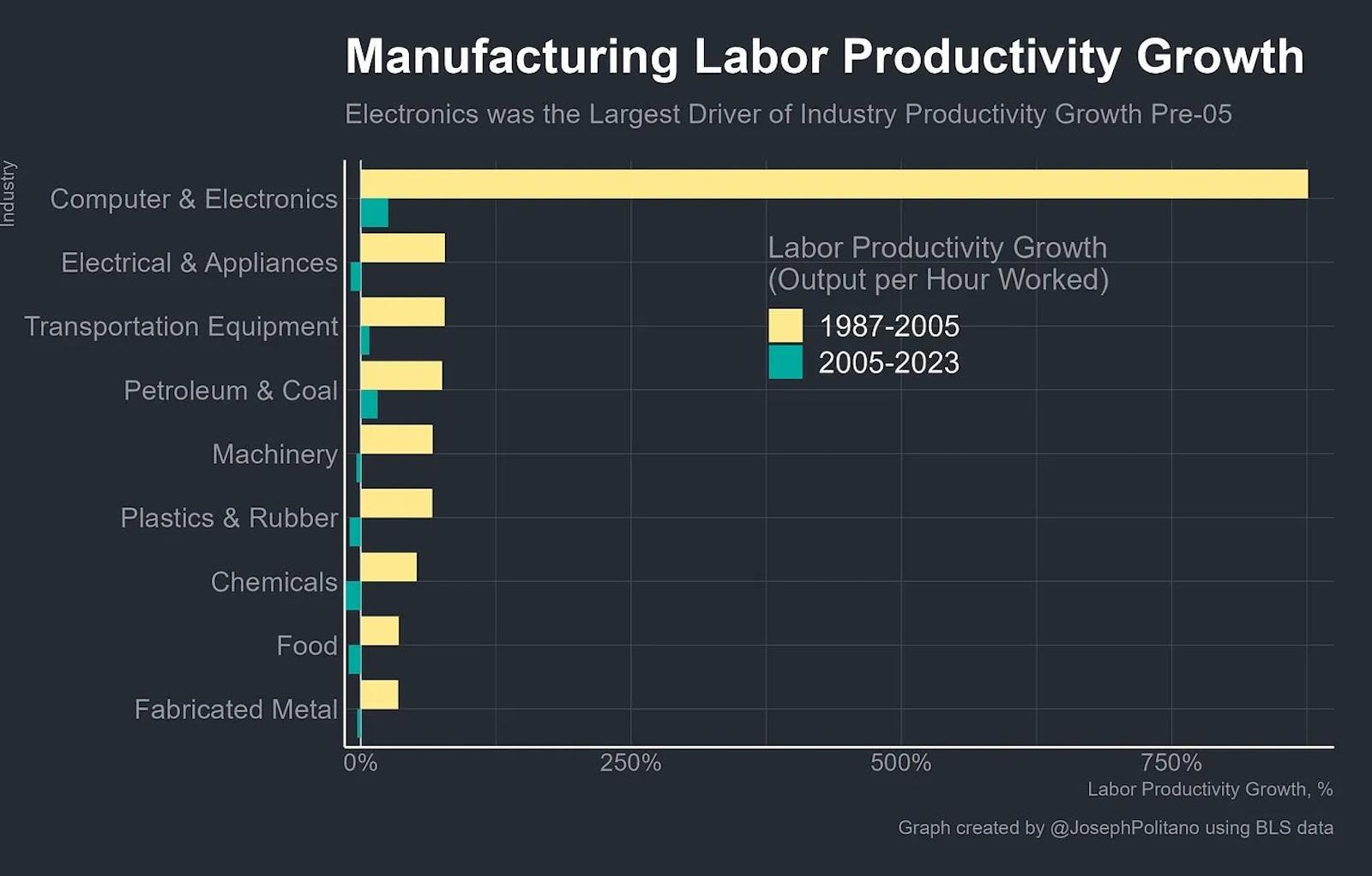

Joey Politano has a good post

where he breaks this productivity stagnation down by industry and shows that it holds true across industries in general. Here's his key graph:

Source: Joey Politano

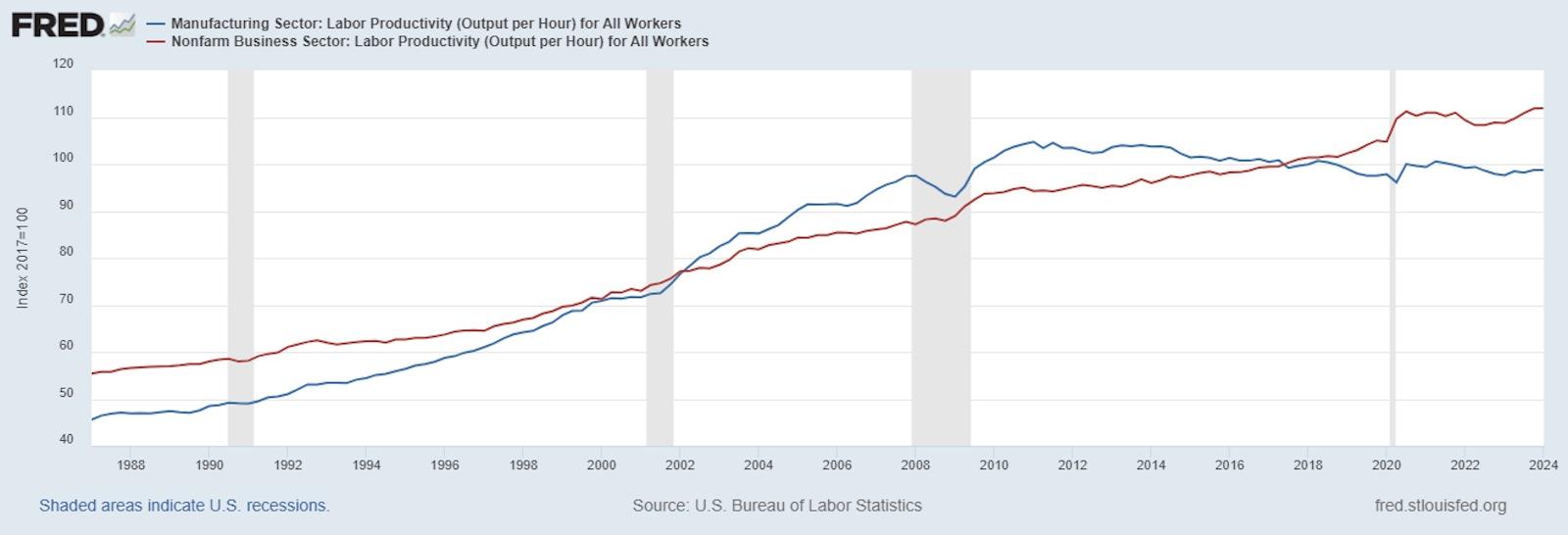

Importantly, this manufacturing slowdown isn't mirrored by a general labor productivity slowdown across the economy! Service industries have been picking up the slack here, and keeping labor productivity growth going:

Service productivity rising faster than manufacturing productivity runs counter to many of the narratives you see in economics and policy debates. But it appears to be the reality for the last 13 years.

Americans seem to be waking up to the fact that something is wrong here.

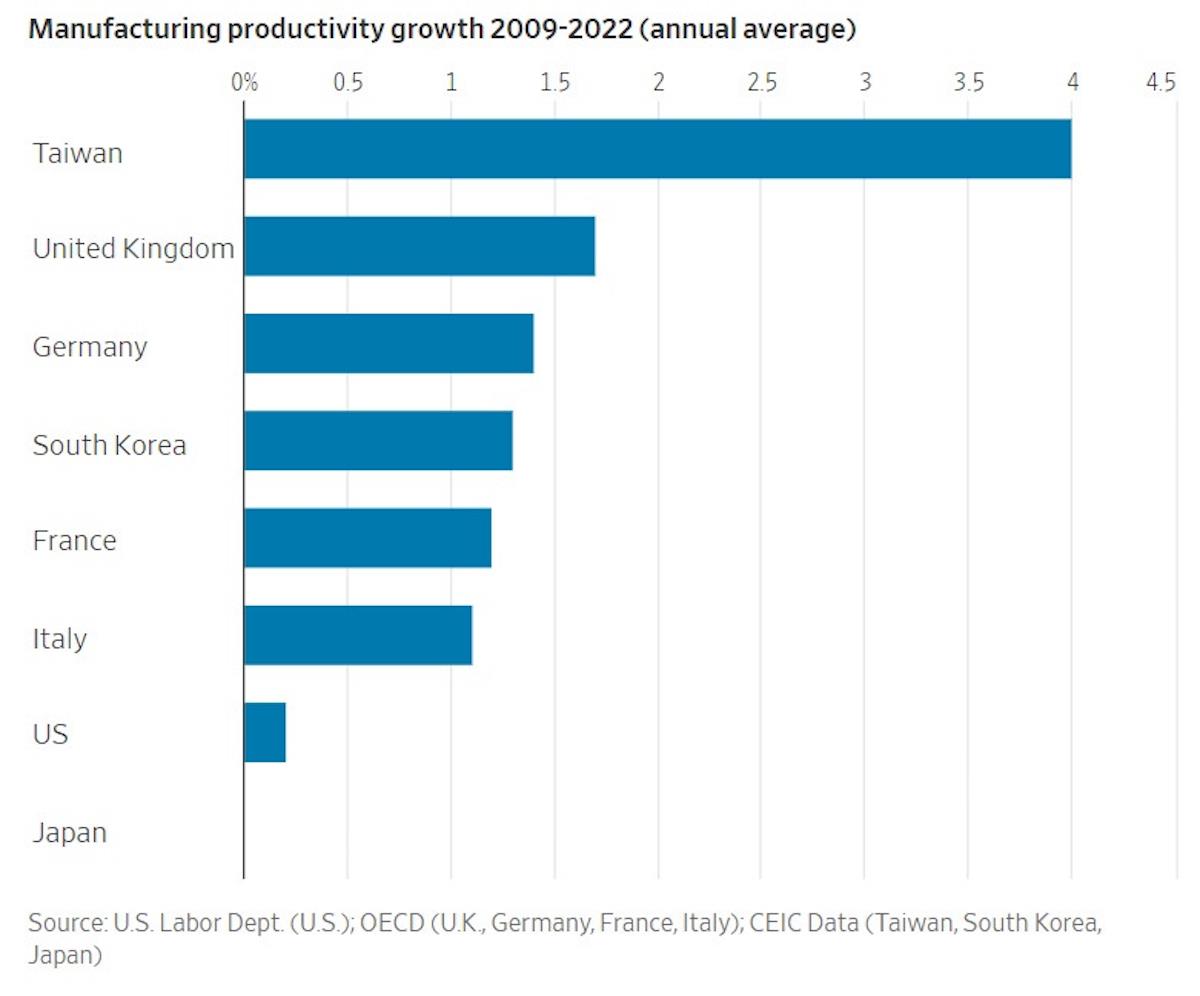

Greg Ip had a good chart

showing that the stagnation in manufacturing productivity isn't worldwide – the US and Japan have done uniquely badly since 2009:

Source: WSJ

A word of caution here: This data is cobbled together from various different sources. One or more of those sources might have

major problems , and even if not, they might make different methodological choices that make them not directly comparable (for example, including subcontractors or not).

But the stagnation is so broadly distributed across manufacturing industries that it's pretty clear something big is going on here. Anyone who wants to revive the US manufacturing sector , for national security purposes or otherwise, needs to worry about the possibility that something is going especially wrong with the American system.

Did the problems begin earlier?

In fact, the troubles might have begun well before 2011, and simply been masked by two other forces: 1) Moore's Law, and 2) China.

You'll notice in Politano's chart that one sector dominated manufacturing productivity growth from 1987 to 2005 –“computer and electronics.” A landmark 2014 paper by Houseman et al. showed just how crucial this sector was to US manufacturing in that era:

And almost all of the growth in that sector was due to quality improvements - the US wasn't producing more computers and computer chips, but thanks to Moore's Law, we were producing better ones:

Now, producing better stuff, instead of more stuff, is real productivity growth! Moore's Law represents real improvement in our productive power. But the fact that quality improvement was the main driver of total US manufacturing output for much of the pre-2011 period means that other things may have been quietly going very wrong in terms of the US ability to manufacture large quantities of output.

And at the same time, there was another factor pumping up the US' manufacturing productivity, especially in the 2010s: offshoring to China.

Until 2001, manufacturing output and manufacturing productivity went up in tandem in the US. Starting in 2001, productivity kept rising for a decade, while output flatlined:

The 2000s were the decade of

the China Shock , when the US – along with many other rich countries – offshored a large amount of manufacturing work to the People's Republic of China.

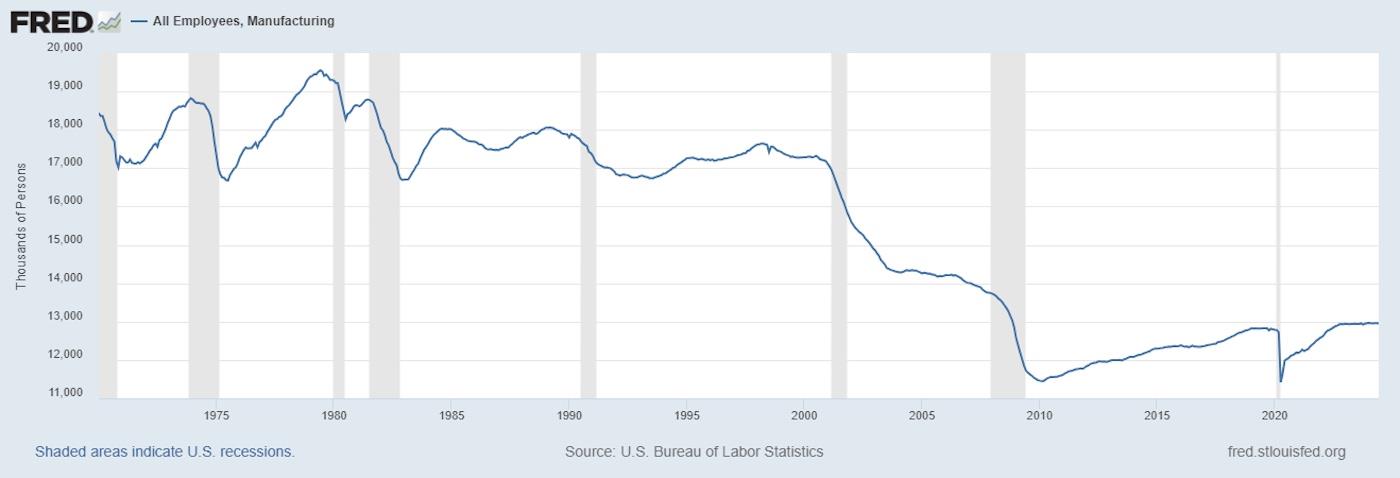

That raised measured manufacturing productivity in two ways. First, there's a composition effect. Remember that in the 2000s, even as US manufacturing output per worker supposedly rose, the total number of manufacturing workers was falling off a cliff:

The most productive US manufacturers tended to stay competitive and survive this devastation, while less productive ones were driven out of business by Chinese competition. That composition effect will tend to raise measured productivity even if it doesn't result in any increase in the productive power of American manufacturing overall.1

Second, offshoring to cheaper countries introduces biases in the data. Houseman et al. (2011) pointed out that when US manufacturers switch to suppliers in cheaper countries, the US government statistics often miss the switch, interpreting it as a rise in product quality rather than a drop in input cost.

That means that the manufacturing productivity benefits of offshoring to China in the 2000s were likely overstated. (Basically, Susan Houseman warned us, and we all should have been paying attention.)

So it's very possible that serious structural problems in US manufacturing were brewing as early as the 90s but were covered up first by Moore's Law and later by offshoring to China.

Anyway, let's talk about some hypotheses as to

why

American manufacturing productivity flatlined.

Hypothesis 1: US manufacturers don't buy enough machinery

One popular explanation for stagnating labor productivity in US manufacturing is

low capital investment. Basically, a factory worker with machines is going to be more productive than a worker without machines. If you look at Chinese factories, they're absolutely chock-full of machinery to help human workers do every task:

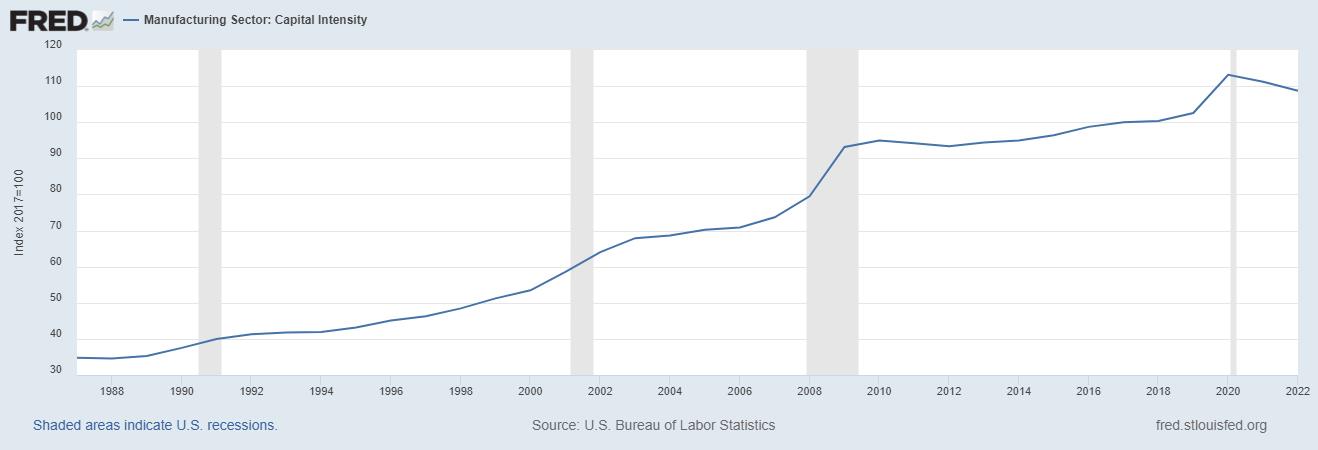

In the US, meanwhile, investment in this sort of capital equipment – and every other sort – has slumped in recent years. Capital intensiveness – basically, the amount of machines per worker – has increased more slowly since the 2009 recession:

Many observers point to this lack of investment as a factor behind slowing productivity. For example, Robert Atkinson of the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation,

writes :

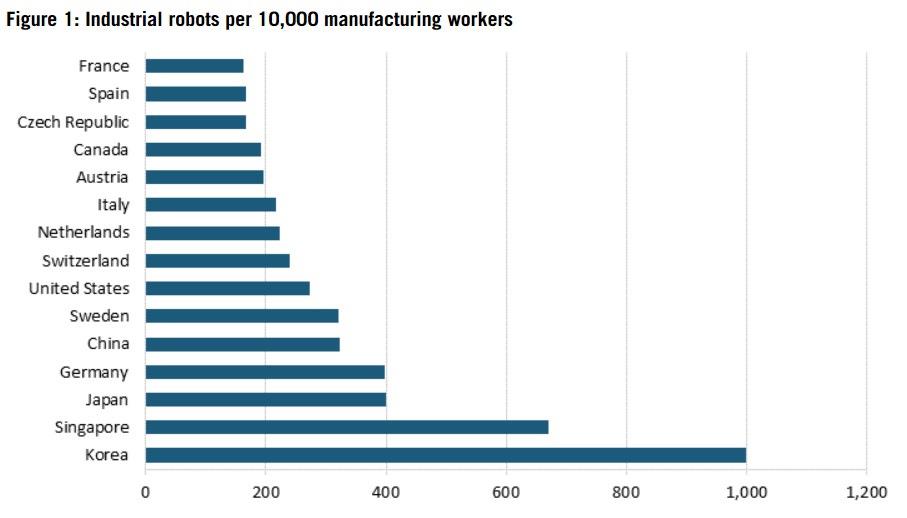

And he posts the following chart:

Source: ITIF

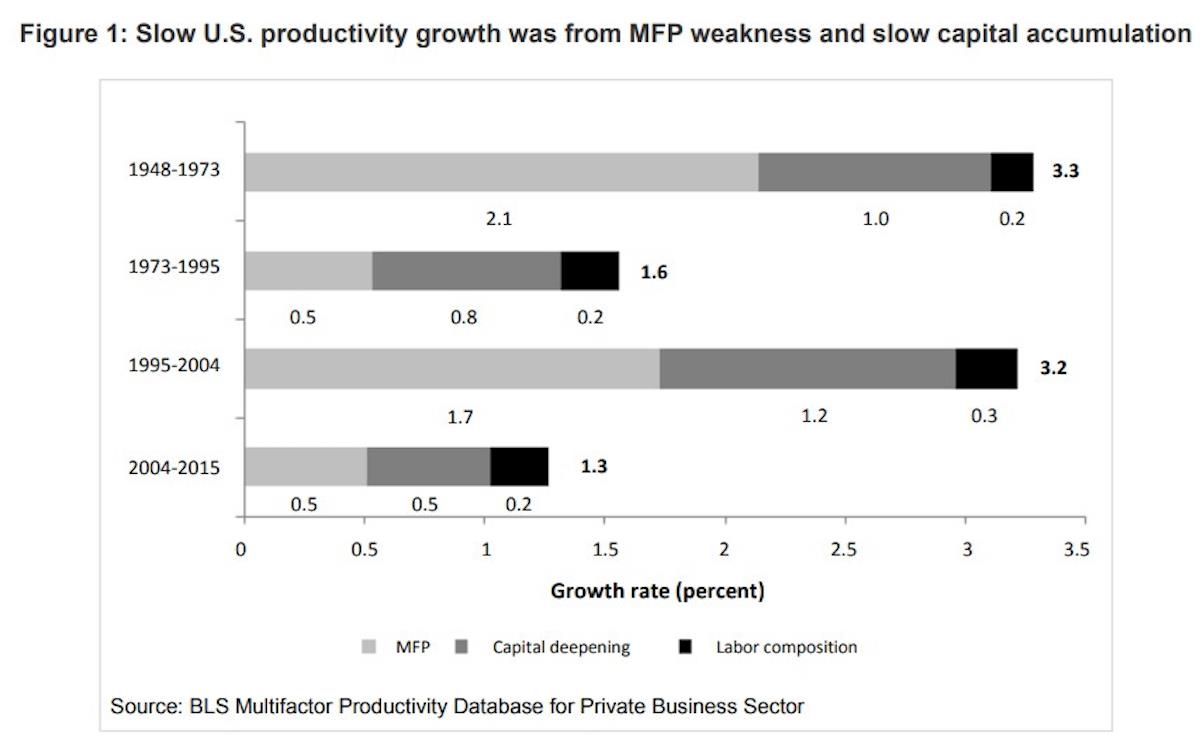

Robots are only one small part of capital investment. But they may be an indicator of a more general failure of capital accumulation in US manufacturing. After 2004, although a drop in total factor productivity (TFP) growth was the biggest culprit, capital deepening (an increase in the amount of capital per worker) also made a much smaller contribution to overall US productivity growth than in the years prior:

MENAFN24072024000159011032ID1108476840

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images, videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.