With Us Or Against Us Amid A Taiwan War

Nearly a month since US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi's visit to Taiwan and China's ballistic response, neighboring Southeast Asia is bracing, calculating and hedging for a potential superpower conflict in its suddenly destabilized backyard.

Opinions in the region appear to be split into three distinct camps. First are the optimists who are downplaying the warning signs on the premise that the gathering geopolitical storm over the self-governing island will dissipate and blow over.

Febrio Kacaribu, head of the Indonesian Finance Ministry's Fiscal Policy Agency, has suggested that the financial impact of a China-Taiwan crisis would be“limited.” On August 5, the Bangkok Post's business section declared“Few fears over China-Taiwan crisis.”

The second camp is already lining up to blame America for unnecessarily stoking tensions. Former Malaysian prime minister Mahathir Mohamad, never one to miss a chance to poke at the West, this month accused the US of trying to provoke a war in Taiwan.

The last group is comprised of the so-called realists, who tend to hold power in the region.

“This is a dangerous, dangerous moment for the whole world,” Singapore's Foreign Affairs Minister Vivian Balakrishnan, said, adding that if US-China relations break apart“it means higher prices, it means less efficient supply chains, it means a more divided world or more disrupted and dangerous world. So those are the stakes.”

Malaysia's Foreign Minister Saifuddin Abdullah has urged all parties to address the situation“in the best manner possible,” while Thai Foreign Ministry spokesman Tanee Sangrat has urged“utmost restraint.”

The foreign ministers of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) bloc — who were meeting in Phnom Penh around the time of Pelosi's visit — have called for all parties to exercise“maximum restraint, refrain from provocative action, and for upholding the principles enshrined in United Nations Charter and the Treaty of Amity and Cooperation in Southeast Asia.”

In nuanced tones, the bloc reiterated its support for the One China“policy” not“principle”: the former a commitment not to recognize the government of Taiwan, the latter a more explicit acceptance that Taiwan is part of China's territory. Beijing considers Taiwan a renegade province that must be“reunified” with the mainland.

No Southeast Asian government – consistent with the vast majority of countries worldwide – formally recognizes Taiwan as a state.

Flags of member countries attending the 35th Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Summit in Bangkok in November 2019. Photo: AFP / Romeo Gacad

Despite the divergent views, a Chinese invasion of Taiwan would be disastrous for Southeast Asia on various fronts. Much of the region's trade passes through the Taiwan Strait, which would likely be closed during a US-China conflict over the island.

Taiwan's exports to the ASEAN region were worth US$70 billion last year. It's also likely in a conflict scenario that trade with mainland China, worth around $878 billion last year, would also be severely impacted, debilitating regional supply chains and economies.

It's almost certain that Western democracies would impose sanctions on China similar to the ones they have leveled against Russia after it invaded Ukraine.

That would likely mean cutting Beijing off from international payment systems including SWIFT, freezing China's $3 trillion of reserves held overseas, banning its banks from trade and other Western-related financing, and even barring its nationals from entering their countries.

If secondary sanctions were applied, Southeast Asian trade with China would also be impacted as nations would be forced to choose between Chinese and Western markets.

Beijing would hardly be in a position to invest as much in wartime as it does in peacetime ASEAN economies. Geopolitically-motivated imports — such as Beijing's promise to buy more Cambodian agricultural produce in helpful response to EU sanctions — would likely be cut or reduced as China refocused its finances on war not trade.

“A war in Taiwan would be a nightmare scenario for Southeast Asian countries as the risk of spillover would be extremely high,” says Nguyen Khac Giang, an analyst at the Victoria University of Wellington.

Southeast has enjoyed a“short peace” since the 1980s, marked by the end of borderland hostilities between China and Vietnam in 1989. The peace has allowed for rapid economic development and growing trade integration, increasing with China at its hub.

A Taiwan conflict, either by mishap or design, would likely quickly spill over into the South China Sea, where Southeast Asian countries, including Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia and more recently Indonesia, have hotly contested Beijing's maritime expansionism in recent years.

China's now heavily-militarized islands and features in the South China Sea would likely be key to its war efforts over Taiwan, including as launch pads for aerial and naval assaults from territories Southeast Asian governments claim as their own.

The China-occupied and heavily-militarized Fiery Cross Reef in the South China Sea. Image: People's Daily

Moreover, if America failed to deter Beijing from seizing Taiwan, there would be little to no deterrence left to prevent China from taking over any territory it desires in the resource-rich South China Sea, including the hotly contested Spratly Island chain.

At the same time, America's counter to China's invasion would likely rely heavily on its dual-use bases in the Philippines, where it maintains rotational troops under a Visiting Forces Agreement (VFA).

Bangkok would also be under pressure to allow the US access to its U-Tapao base, which the US used to strategic effect during the Vietnam War. In 2019, Singapore signed a deal that allows the US access to its naval and air bases until 2035. Any British intervention would likely entail the use of its naval facilities in Singapore and Brunei.

Yet it's still an open question how individual Southeast Asian governments would respond to a Chinese invasion of Taiwan. For that, much depends on the type of conflict that erupts, analysts say.

If Beijing was able to quickly and without too much loss of life seize quick control of Taiwan before the US could mount a response, most Southeast Asian governments would accept the fait accompli, says Chong Ja Ian, a political scientist at the National University of Singapore.

Southeast Asian responses would become more complicated, however, if a protracted conflict ensued. US President Joe Biden has several times said that the US would defend Taiwan, even though his spokespeople later sought to murky his comments and claim Washington still pursues“strategic ambiguity.”

But the growing sense, including in Southeast Asia, is that the Biden administration has become strategically unambiguous, meaning it will try to defend Taiwan and thus any Chinese invasion attempt will result in a superpower conflict in the region's backyard.

A substantial American intervention on behalf of Taiwan would change the stakes considerably.

Most analysts who spoke to Asia Times were of the opinion that a majority of Southeast Asian countries would, in that event, turn against China and side with the US, largely over the fears of the precedent it would set in a region riddled with territorial disputes.

Only Laos, Cambodia and Myanmar would likely back Beijing, likely while professing“neutrality”, the analysts said.

“It is unlikely for us to see a united ASEAN voice on the matter,” says Joshua Bernard Espeña, resident fellow at the International Development and Security Cooperation, a Manila-based think tank.

Chinese President Xi Jinping (L) and Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen (R) toast in Phnom Penh in a file photo. Photo: AFP / Tang Chhin Sothy

One thing is clear, however: a protracted conflict in Taiwan would signal the end of the region's peacetime status quo. It would also terminate the region's current policy of hedging between the US and China: No government in Southeast Asia wants to choose sides, but a conflict over Taiwan would inevitably force them to do so.

After the Russian invasion of Ukraine earlier this year, most Southeast Asian governments professed neutrality. Lurking behind government speeches was a sense that it was a distant war that meant little to them economically or strategically.

The same wouldn't be true if a conflict erupted over Taiwan, which is just a little over 1,200 kilometers from the tip of the Philippines.

Laos, Brunei, Myanmar and Cambodia would likely try to sit out the conflict and defer their voices at the ASEAN level, said Espeña. Singapore, Vietnam and Indonesia will“express extreme worries and place their defense on high alert. Thailand and Malaysia might diplomatically condemn China but they will still urge restraint to all parties,” he predicted.

“Since Manila is the most proximate Southeast Asian country as well as a US treaty ally, the Philippine government will likely fulfill the obligations to the 1951 Mutual Defense Treaty despite domestic anxieties that the Americans might be dragging the Filipinos again like the last war in 1941,” Espeña said.

As well as the Philippines, Thailand — America's other treaty ally in the region — would potentially be involved in the conflict, says Joshua Kurlantzick, senior fellow for Southeast Asia at the Council on Foreign Relations.

For years, Bangkok has been the region's arch-hedger between the US and China. On August 14, the Chinese and Thai Air Forces held joint drills. Nonetheless, at a meeting in July between US Secretary of State Antony Blinken and Thailand's Foreign Minister Don Pramudwinai both affirmed their long-held treaty alliance. Thailand was elevated to a“non-NATO” treaty ally for its assistance in the US“war on terrorism.”

“If China invades Taiwan – other than Laos, Cambodia, and Myanmar – I would expect to see a significant ramp-up in arms purchases in Southeast Asia, which is already a major center for arms purchases, and closer ties to anti-China forces in the region: Japan, Australia, the US,” says Kurlantzick.

From August 1-14, Australia, Japan and Singapore participated in the US and Indonesian“Super” Garuda Shield drill. Singapore will come under pressure to stand by its principle of opposing any violation of national sovereignty, which led it to impose its own sanctions on Russia for its Ukraine invasion.

Whether the city-state would unilaterally sanction China is another matter altogether. Analysts say it may well seek security through a joint sanctions program, along with the likes of Japan and South Korea.

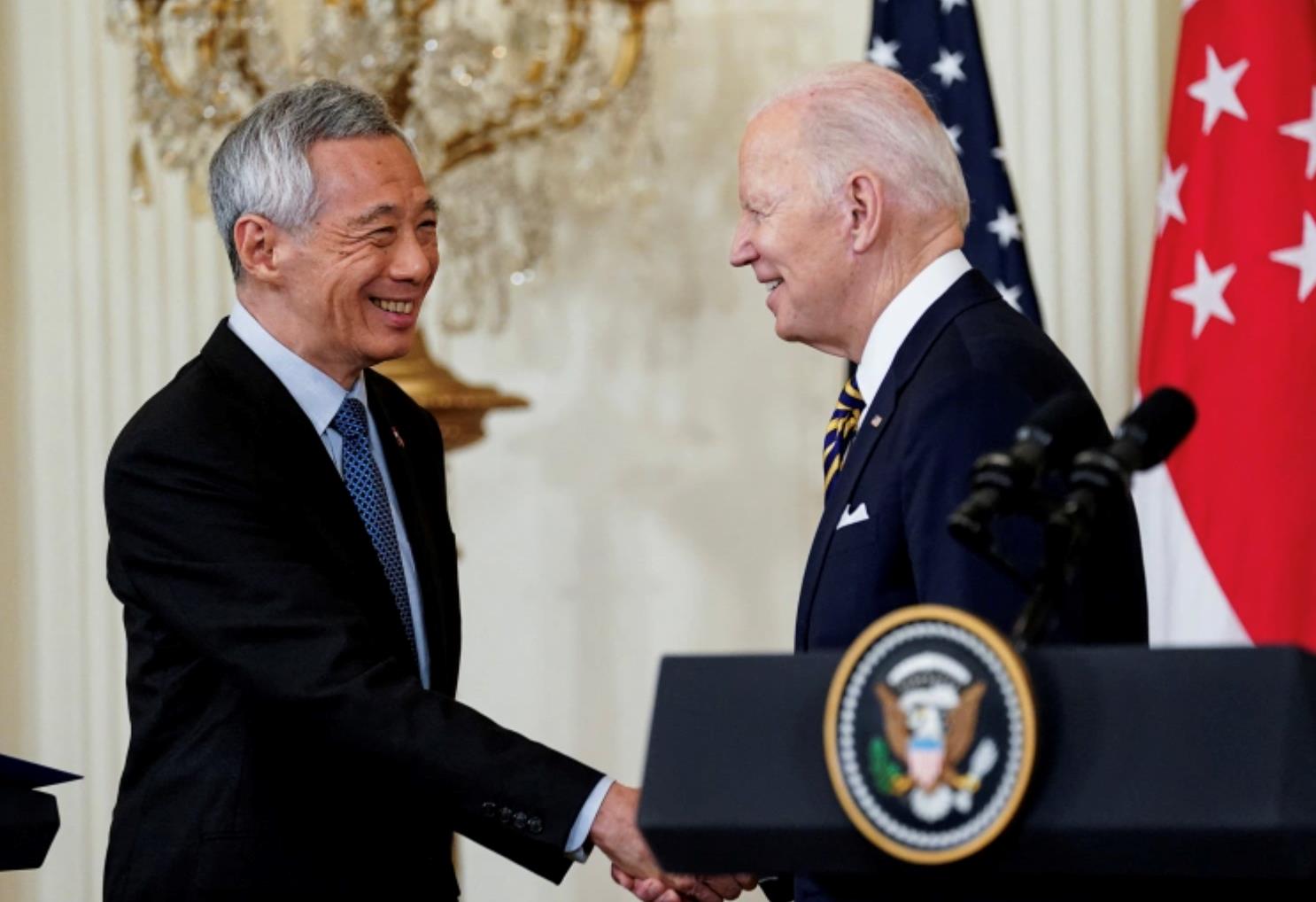

US President Joe Biden and Singaporean leader Lee Hsien Loong largely see eye-to-eye. Image: Handout

Geographic location may also dictate how individual states respond, says Chong.“States that straddle important air, sea and communication links or are physically close to Taiwan may face pressure from both Washington and Beijing to block the other.”

“The US needs access through these areas to move its assets from the Middle East and the Indian Ocean. US allies South Korea and Japan, and indeed Taiwan, need these areas for access to energy from the Middle East and trade. Trade and energy imports through these areas are likely important to China,” Chong said.

Which way Southeast Asian governments swing could in the end be driven by realpolitik. In the event of a drawn-out conflict, Southeast Asian capitals are“likely to side with whom they think the eventual victor may be,” Chong added.

Many analysts reckon it will be extremely hard for Taiwan, even with full US assistance, to defend itself against China's overwhelming forces. Western-led sanctions on Beijing, meanwhile, would likely be less damaging than the ones now imposed against Russia, which to date have been frail and largely ineffectual.

Regional states with South China Sea disputes with China — particularly Vietnam, the Philippines and Indonesia — may consider if supporting the US would allow them to gain an edge in their bilateral disputes with Beijing, Chong said.

Vietnam, for one, has been cagey about formally advancing its relations with the US due to concerns China, its largest trading partner, may retaliate. But Hanoi could side with the US amid a Taiwan war, especially if Beijing advances slowly, due to concerns its claimed territories could be next in China's sights once mobilized militarily.

Surveys on Southeast Asian public opinion about a potential Taiwan war are few and far between, making it difficult to predict how regional governments may respond.

The Democracy Perception Index 2022 survey, published earlier this year by Latana and the Alliance of Democracies Foundation, asked respondents:“If China started a military invasion of Taiwan, do you think your country should cut economic ties with China?”

Indonesians were in the top three national groups that wanted to maintain ties. A net majority of respondents from all six Southeast Asian states surveyed said their governments should maintain economic relations, including Vietnamese and Singaporeans. Filipinos were nearly divided equally on the question.

Follow David Hutt on Twitter at @davidhuttjourno

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment