(MENAFN- Asia Times)

Acclaimed author Robert Whiting is so tightly plugged into Japan that the first edition of his memoir Tokyo Junkie: 60 Years of Bright Lights and Back Alleys … and Baseball came out in Japanese. Then the editors of the English edition, for whatever reason, decided against including his material on espionage. That decision is our readers' gain. Asia Times earlier published one of those segments and now we're serializing the other. Part 1 is here , Part 2 is here , Part 3 is here and the concluding installment, Part 4, follows below:

At Fuchu Air Station's Elint, we were constantly reminded that our enemy was communism – Russian, Chinese, North Korean communism – and warned that there were communist spies in our midst. We were instructed to always be on guard.

That was not new. In Tokyo before my time, starting in 1946 in the early Occupation period, there had been the black ops Canon agency. Lieutenant Colonel Jack Canon's anti-communist spook agency was all about guns, midnight assignations and the third degree, .

“Loose lips sink ships” was the pet phrase of the aphoristic Navy chief petty officer who was my immediate boss,“If you are asked what you do, just say you are a radar operator. Don't get drunk in the presence of strangers – and that includes the women off-base.”

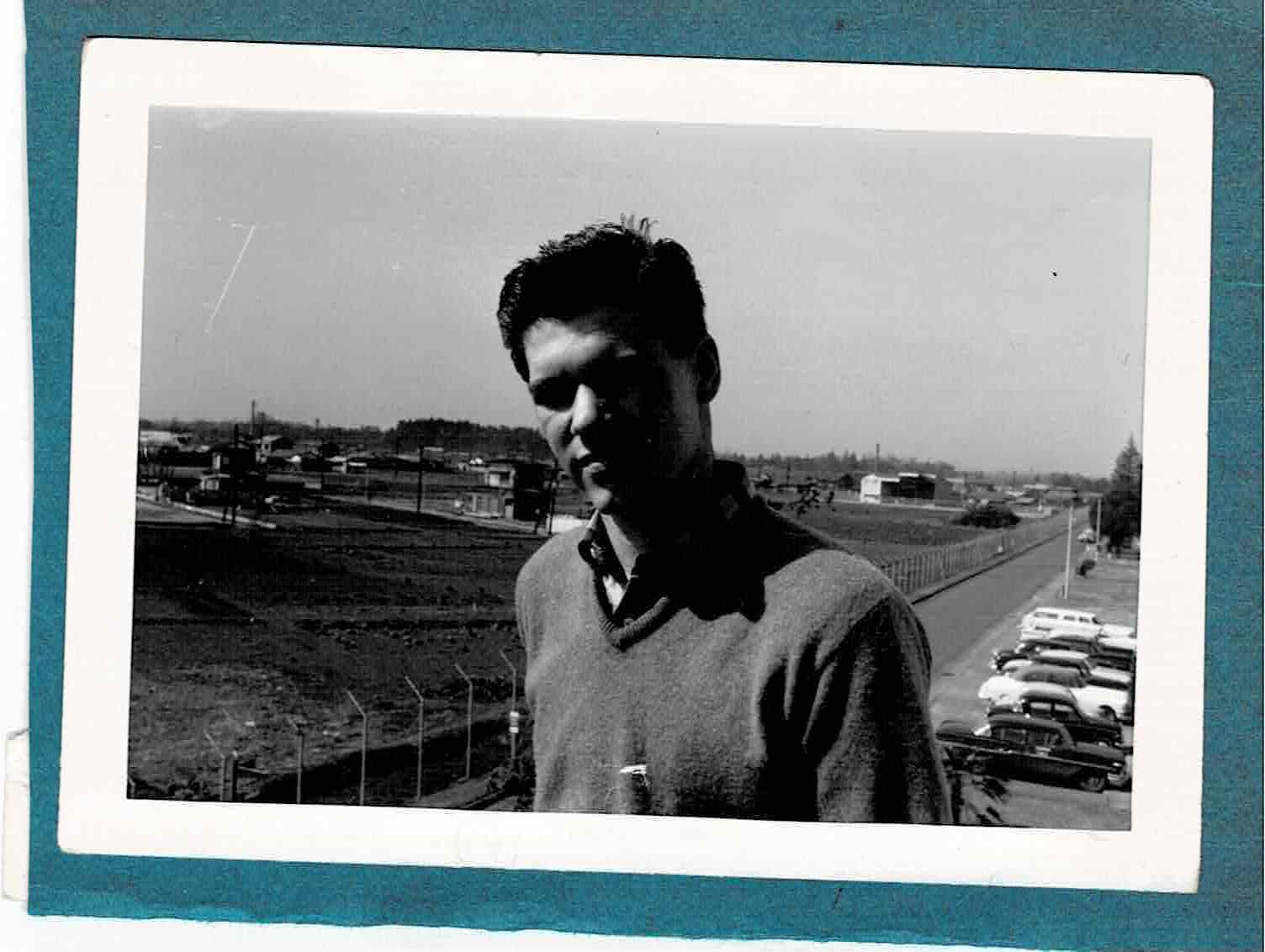

The author at Fuchu Air Base. Photo: courtesy Robert Whiting

The Japan Communist Party had been active since the days of the Occupation. It had only 50,000 members, but it was supported by both China and the Soviet Union, which had helped to subsidize demonstrations against the U.S. presence in Japan.

Tens of thousands of ordinary Japanese, normally apolitical, had opposed the extension of the US-Japan Security Treaty in 1960 and marched in protest in the months of May and June of that year.

But the most virulent opposition came from the ideologically committed students of the Zengakuren, the tightly disciplined communist-led All-Students Association, who spearheaded violent clashes with the riot police and who, according to first-hand reports, were financially supported by the JCP. Student protestors were said to have been paid 200 or 300 yen a day plus a free bento (boxed lunch).

On the evening of June 5, 1960, some 14,000 members of the Zengakuren had attacked the Diet Building compound in a futile attempt to block the passage of the extension of the revised Security Treaty, throwing stones and wooden spears at a phalanx of 4,000 steel-helmeted riot police. In the melee, a 22-year old Tokyo University student was trampled to death. The protests were so violent that a planned visit by US President Dwight Eisenhower had to be canceled.

“Moscow and Peking have made it abundantly clear that the neutralization and eventual take-over of Japan, is their number one objective,” said the previous US Ambassador to Japan, Douglas MacArthur II, nephew and namesake of the Pacific War and Occupation generalissimo.

In the minds of most US military officers, everybody outside the center was suspect – Japanese nationals waving political banners near the entrance, photographers on the other side of the chain-link fence taking photos of the facility through zoom-lens cameras.

We were told to be vigilant at all times, to beware of the Japanese papa-san who drove us on intelligence exchange trips to the Yokosuka and Atsugi naval bases, the Japanese waitresses who served us in the Airman's Club, the manager of the Korean style yakiniku restaurant up the road where we sometimes ate, the Chinese proprietor of the Daihanten restaurant down the street and any patron of the bars on the strip who was not an identifiable American military or civilian worker, such as the old White Russian drunk, a longtime Fuchu resident, who hung around the bars on the strip speaking to us in his broken English. They were all potentially spies.

There were also the odd shady characters hanging around outside the gate, in the bars, and on the strip, looking to buy weapons. It was hard to tell whether they were simply yakuza doing yakuza business or red agents with more sinister motives.

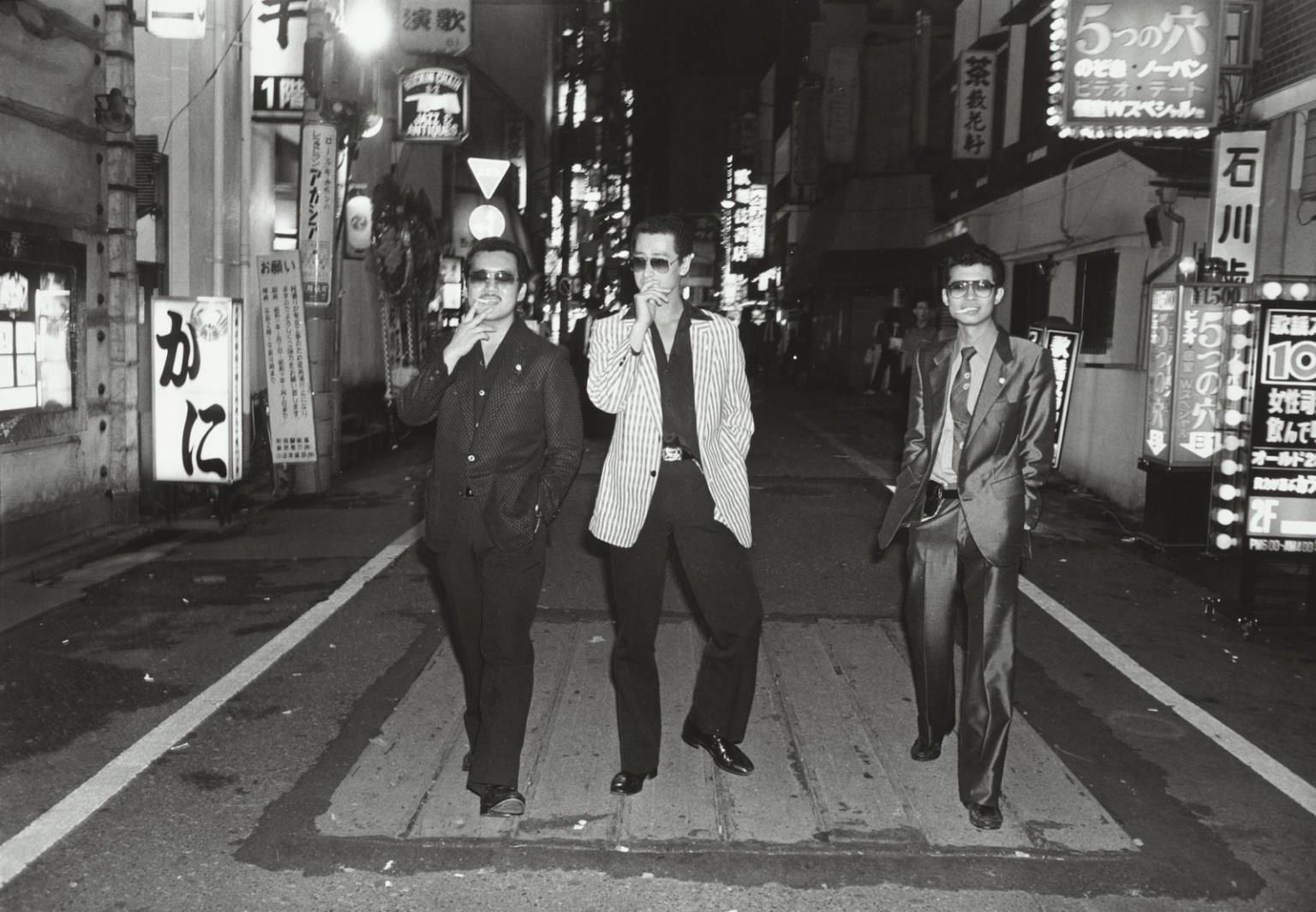

Some 'family' friends of the author. Photo: Tokyo Junkie

Others were there to peddle drugs – some for profit; others, so we were told, for the purpose of addicting GI's so that they would spill military secrets or, at the very least, be useless as enemy soldiers.

If there was a visible trade in weapons, however, I never saw it, although there were occasional reports of GI's arrested in other base towns, Tachikawa or Yokosuka, selling guns.

I knew an air policeman who was stupid enough to sell his sidearm for a couple of hundred bucks and then claim it was stolen. He wound up in the brig. (He was almost as dumb as the AP guard doing an overnight at the Elint Center who was so bored he started playing with his sidearm and wound up shooting himself in the hand. The desk by the entrance was covered in blood and bits of flesh as we walked in that morning. They sent him back to the States.)

Drugs

Drugs were a little more conspicuous. Every now and then you would be approached by someone on the strip who asked if you were interested in shabu (speed). I never took the bait but I knew of a couple of guys who did and who were caught and cashiered back to the States and out of the military.

There were also heroin dens outside the base in Tachikawa. A large population of Chinese and Koreans residing in Tachikawa City was said to be sympathetic to the communist cause, engaging in espionage and sabotage. According to one report in the Nippon Times, by the end of the Korean War in July 1953 there were dozens of heroin dens and hundreds of single users.

GI's serving in South Korea added to the mix. They would develop the habit there, usually getting their heroin from bar girls in South Korea, and bring their drugs back to Japan. Some of them were even dealing, selling it to the yakuza.

The military had cleaned it up some since then, but not completely. I knew a guy named Deckman, an airman in the admin department who lived in the room next to mine in the barracks. He went to one of the dens and wound up hooked. He pointed it out to me as we walked by one day on our way from Tachikawa train station to the base.

It was just a house, a non-descript western-style house not far from the main gate. He said you went in and sat down in the living room and some mama-san presented you with a menu.“Of course, this being Japan,” he said,“you always get a nice hot towel and a cup of steaming green tea to go with it.”

The options were the pipe, the cigarette, and the needle. You licked the cigarette and dipped it in a bowl of heroin powder, then lit up. Well, he kept going back and soon he had graduated to the needle. Medics responding to an emergency call from the house found him writhing on the floor in agony. They shipped him back to the States, as well. The last I heard he was living on the streets of downtown Los Angeles.

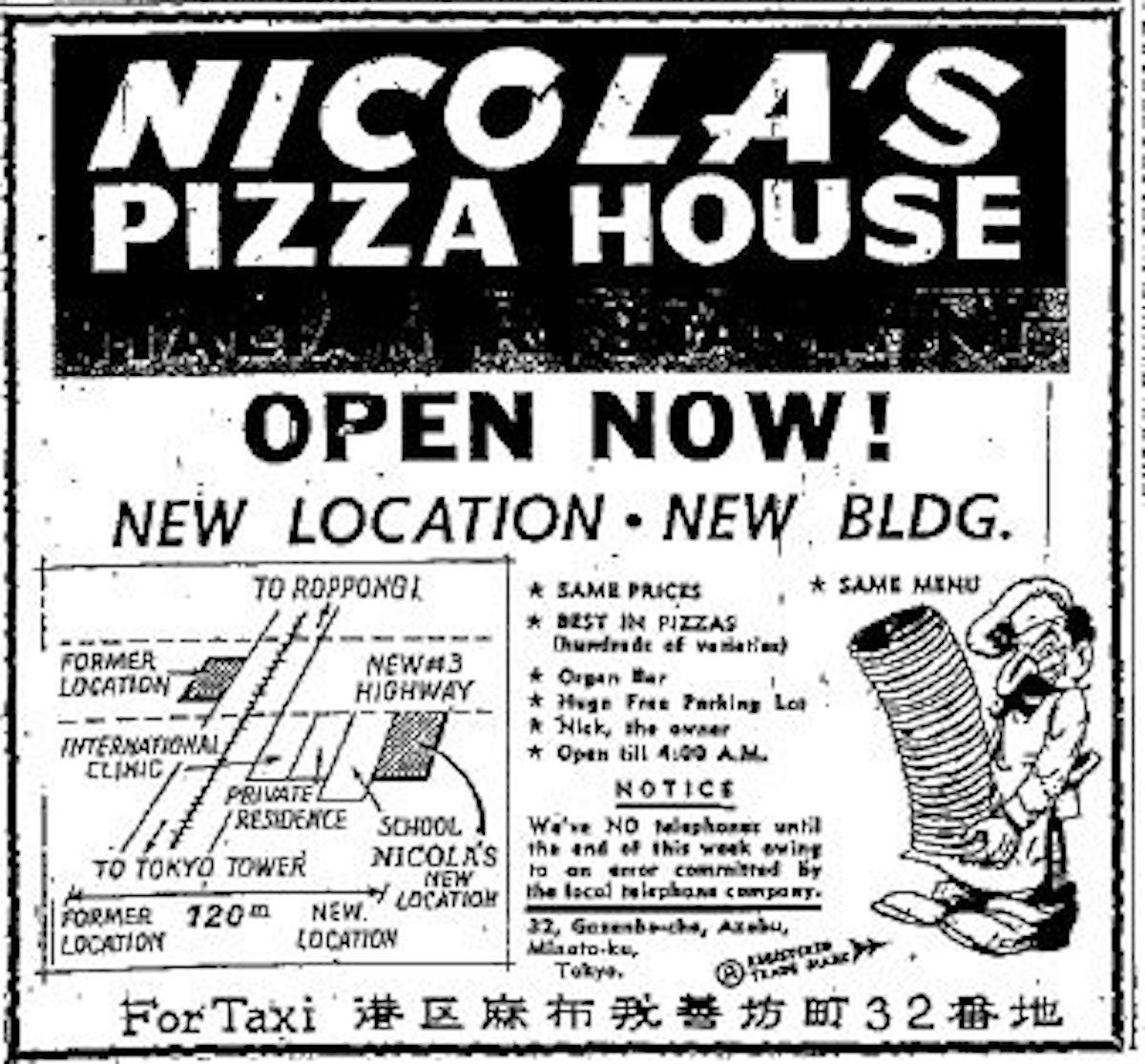

We were told to exercise particular caution in the Roppongi/Akasaka area on our sojourns to central Tokyo because, according to the Navy chief I worked for, it was a“hotbed of communist spies.” The Soviet Embassy was just steps away from Club 88 and Nicola 's pizza parlor, to both of which Soviet agents were frequent visitors.

We received reports of Russian agents attempting to bribe American employees of the military's Stars and Stripes newspaper, for example, to get information on the activities of the US military inside American bases.

One who was approached, an editor named Tom Scully, whom I later became friends with, was wined and dined repeatedly by a Soviet agent, who offered Scully thousands of dollars in cash and other perks to come over to the other side. Scully enjoyed the wining and the dining but turned down the money. He reported the agent to the Japanese authorities, who deported the man.

Hounding Dr Aksenoff

A locus of activity that aroused interest was the International Clinic, directly across the street from Nicola's. It was run by Dr Eugene Aksenoff, a White Russian whose parents had fled to Harbin, China during the Bolshevik Revolution.

From there he had come to Tokyo before the war as a medical student. He'd paid his tuition by acting in Japanese war propaganda films – playing captured American pilots, never mind that he spoke his American English lines with a thick Russian accent.

He'd stayed on, stateless, a man without a passport, setting up his clinic. The doctor spoke fluent Russian and the leather chairs in his waiting room were filled with patients from the nearby Russian Embassy, reading Russian language periodicals.

Aksenoff was known as a man of integrity and honor, and politically neutral. But with the Cold War at its peak, that fact alone was enough to attract the attention of Japanese authorities, who suspected that a communist lurked behind every cherry tree.

They based their suspicions in part on a report prepared by US military intelligence in 1954 that designated Aksenoff as a communist agent, after a defecting Soviet diplomat had fingered him as such. The diplomat had been an associate of the infamous Soviet secret police chief Lavrenty Beria who had just been executed in Moscow.

Fearful for his life, the diplomat had decided to cross over to the American side. Lacking anything substantial in the way of information to barter, he'd concocted a story that Aksenoff had been providing treatment for young GIs with venereal diseases – STDs as they are now called – who were afraid to go to the base hospital and thus run the risk of being discovered and punished by their superior officers.

In return for doing this, according to the diplomat, the GIs were giving Aksenoff US military secrets, which Akensoff then passed on to his friends at the Soviet Embassy.

There was never any evidence produced that this was remotely true, but because of these reports and the indisputable fact that Aksenoff's clinic was, in fact, only a city block from the Soviet Embassy in Azabu, Aksenoff had been under constant surveillance as a result.

Undercover detectives followed him around Tokyo in taxis and unmarked cars. They dined at the same restaurants and they tapped his phones (so badly, in fact, that Aksenoff remarked to friends that he could hear the cops talking to one another).

The Japanese police eventually arrested him, years later, on charges that he had installed a radio transmitter in Kawasaki, south of Tokyo, near a new clinic he had ostensibly set up for visiting sailors. The authorities had received an unconfirmed report from an unidentified witness that Aksenoff had been seen burying equipment at the site and when they unearthed it, they found that part of the device was marked with what looked like a Russian Cryllic number four.

That was the clincher and the detectives had come to Aksenoff's residence, clapped with handcuffs, tied a rope around his body, as per police custom, and led him off to jail, where they kept him for several days.

He was released only when an embarrassed Toshiba engineer came forth, after reading about the matter in the newspaper, and explained that the transmitter was an experimental device that belonged to his company and the symbol that had so impressed the police as evidence of Russian espionage was in fact a symbol Toshiba used for digital equipment.

Whoever identified Aksenoff as being at the scene, Aksenoff later surmised, was probably a business rival unhappy that the new Kawasaki clinic was taking away patients.

Speaking of patients, Aksenoff was known as“doctor to the stars”: He treated Brad Pitt, Angelina Jolie, Michael Jackson, Madonna and John Wayne – not to mention Jacques Chirac and Nick Zappetti.

I knew Aksenoff very well, interviewed him several times for Tokyo Underworld and Tokyo Outsiders. He told me in detail the story of his bizarre relationships with the police. He said one reason he remained stateless was to remain as apolitical as possible so as not to interfere with his medical practice – and, I might add, his pursuit of wealth. He owned a couple of buildings.

Said Aksenoff summing up the whole experience when it was all over, “In both cases, the police knew there was nothing there. They had to create fear that there were Russians in the country to keep anti-communist feeling high. They needed a Russian spy and I was it.”

Follow Robert Whiting on Twitter: @robertwhiting_ and, starting this week, readers can find the author's regular commentary on Japanese sports, politics and business on Substack .

MENAFN03022022000159011032ID1103639590