(MENAFN- Asia Times) Kiyevskaya Street is one of the busiest in the Kyrgyz capital of Bishkek. Monumental Stalin-era architecture, elegant lamp-poles, flower-beds and two lines of tall poplars make it a hot spot for locals.

What makes it even more popular is a spacious campus bustling with activity and teeming with thousands of young residents. It is a magnet for local ethnic Russians and urbanized Russian-speaking Kyrgyz alike.

The institution, Kyrgyz-Russian Slavic University, is an educational landmark that symbolizes Russia's strong cultural bridgehead in Central Asia. It is the school of choice for the local elite – mirroring the close ties between Bishkek and Moscow.

Boasting almost 2,000 teaching staff, it was established in 1993 and is today named for Russia's first president, Boris Yeltsin, who actively courted the Kyrghyz and visited in the 1990s. A bronze bust of the man stands in the main university building.

There are several more Yeltsin monuments across the country and one of the summits of the iconic Tian Shan mountains, 5,168 meters up, was recently renamed 'Yeltsin Peak.'

Yeltsin is just one example of the Russian presence and influence that, despite the breakup of the Soviet Union, remains ubiquitous across Kyrgyzstan – and across Central Asia as a whole. Yet in today's post-colonial age, and in a region where local nationalism and Islamicization are rising, questions are beginning to appear over the Stans' Russian heritages.

A deep footprint Bishkek was founded by Russian settlers and Cossacks in the 19th century and was overwhelmingly Russian up until Kyrghyz independence. Today, almost 30 years later, the city's Russian community is shrinking amid rising Kyrghyz nationalism and Islamic activism. But it is impossible to overlook Soviet and Russian and Soviet structures.

There are Pushkin and Tolstoy streets, monuments to Russian generals and politicians, a Russian theater in the city's green center of the city, a Russian war memorial, a massive stone grey-stone Russian library, a Russian-style circus…and it is not just heritage.

Ties are economic, too. The som – the local currency - is pegged to the Russian ruble and strongly supported by the Russian economy and trade. The US dollar exchange rate for both som and ruble is pretty much the same: 60-65 to one dollar at the time of writing. That makes the som the strongest currency in Central Asia, on a par with Russia's.

The exchange rate, coupled with booming Kyrghyz-Russia trade, means Bishkek's stores and supermarkets look like Russia's: The same food fruits and vegetables are sold at almost the same prices as in any small Russian town. Probably 80% of foodstuffs in Bishkek stores originate in Russia.

The interior of a classically Russian restaurant in Almaty. Photo: Alexander Kruglov

The diets of both Kyrghyz and Kazakhs are heavily influenced by Russia – the result of over a century of Moscow rule over these nomadic nations. Russian-style cottage cheese and sour cream; oatmeal and buckwheat; and of course, the dozens of kinds of potatoes and the multiple kinds of black rye bread that Russians call 'black bread' – all are easily available.

…and in the same restaurant, a very Russian meal served on the plate. Photo: Alexander Kruglov

Then there is the written word. A huge number of ethnic Russians and Russified locals encourage book and media exports: This is what the Kremlin's 'Russky Mir' ('Russian World') soft-power project is all about.

Thousands of titles from Russia's thriving publishing industry are exported every year and sold across the region. Moreover, over 60% of local publishers' output is in Russian.

Not only are the glitzy magazines available in Kyrgyzstan also from Russia, major Moscow dailies print 'local' editions in Bishkek. These are printed simultaneously – in Russian – with about 70% local reporting from ethnic Russian journalists. TV channels are also predominantly Russian, or broadcast in Russian.

Kazakhstan's biggest city – Almaty, a former capital – looks even more Russian. Endless rows of Khrushchev-era five-story apartment blocks are laid out on a Soviet-style grid plan of the 1950s.

With a 30% Russian population, Russian shop signs are everywhere, Russian restaurants rule the local culinary roost, and a major pedestrian thoroughfare is called Arbat – just as in Moscow.

Russian pop-music blares as hip-hop singers and break-dancers, acrobats and street painters do their thing. Groceries mainly sell Russian food, bookstores are stocked with Russian best-sellers, and local movie-theaters play the latest Russian releases.

Russian-style buildings in the famed Silk Road crossroads of Samarkand. Photo: Alexander Kruglov

But the deeply entrenched bridgehead of the former colonists does not please everyone.

Rising tide against Russiana

Ever since the break-up of the USSR in the early 1990s, there have been attempts to limit Russian influence in the region. For example, Muslim activists are furious about new Russian churches being built, while nationalists push against schools using Russia-centric curricula.

A Russian Orthodox church in Samarkand. Photo: Alexander Kruglov

However, it is not just extremists and nationalists who want to limit the use and/or expansion of Russian culture. Authorities, too, are putting the brakes on.

A critical point of contention is language. Russian remains the essential lingua franca of the region, but local leaders often see this as encroaching upon their sovereignty and cultural identity. Former Uzbek strongman Islam Karimov was the first regional leader to ditch the Cyrillic script and switch to Latin characters.

That switch proved irksome for both Uzbeks and Russians. With many novels now appearing in both Cyrillic and Latin – a heavy burden has been placed on the publishing industry.

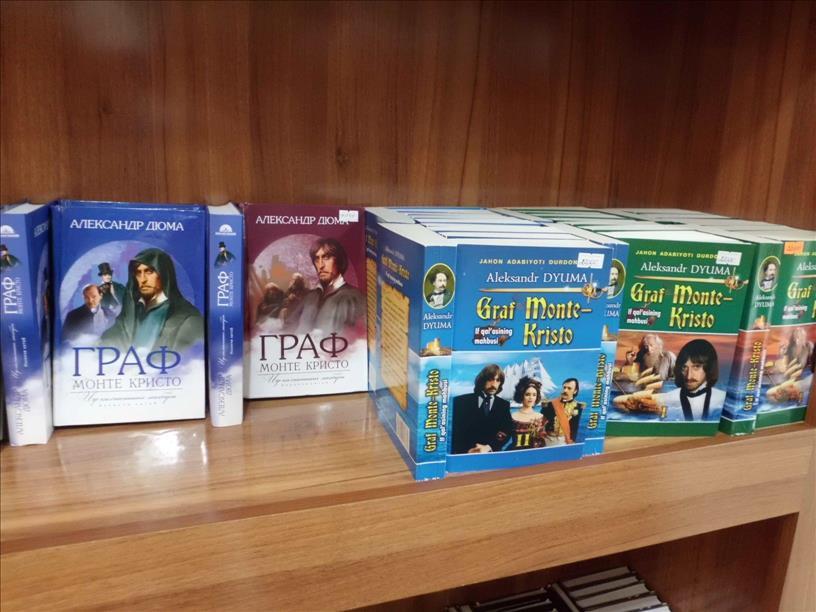

Two copies of Dumas' popular classic "The Count of Monte Cristo" in an Uzbek bookstore: Cyrillic on the left, Latin characters on the right. Photo: Alexander Kruglov

A similar switch to Latin script in Kazakhstan proved even more shocking for ethnic-Russian locals.

'Kazakstan is the wrong place for this kind of experiment,' said Vladislav Akimchuk, an ethnic Russian journalist, based in Almaty. 'With such a heavy non-Kazakh minority, Russian has traditionally been the inter-ethnic means of communication.'

The politics behind the move are clear, according to Akimchuk.

'Here in Almaty, we all know that the real motivation was to prevent separatism and to tighten the Kazakh grip on this land,' he said. 'But will it work in such a vast, multi-ethnic country? That's another question.'

For the moment at least, efforts to ditch Russian script look both costly and futile. Most local Kazakh papers are still published in Cyrillic, and most billboards and ads are still in Russian – just like before.

Yet these official efforts to limit Russia's language, script and religious institutions make clear the future challenges facing Russky Mir across a region that is forging its own future.

Not coincidentally, ethnic Russians who have not fled to "Mother Russia" in the years since the USSR imploded are increasingly wary about their place in the new Central Asia.

MENAFN1412201901590000ID1099423793

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images, videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.