Master musician was 'the father of modern Korean music'

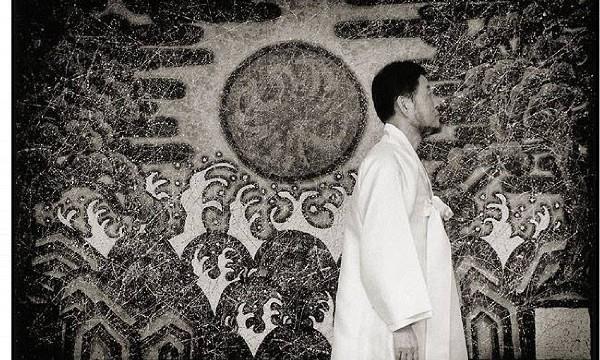

Few can claim to have engineered the preservation and advanced the forward momentum of a nation's traditional music. Korean master musician Hwang Byung-ki did both.

Many consider Hwang, a master of the stringed instrument the gayageum, 'the father of modern Korean music'— a mandate that now passes on to his disciples following his sudden passing on January 31, 2018, from pneumonia after complications from a stroke.

Must-reads from across Asia - directly to your inboxBorn in 1936 in Seoul, Hwang was the first musician to study both elite court music and folk music (traditions that use two differently shaped gayageum) at what is today called the National Gugkak Center (formerly the National Center for Korean Traditional Performing Arts). Hwang started his studies in Busan (then spelled Pusan), in Korea's southeast, where the center's musicians had fled after Seoul fell to North Korean forces in 1950. The center's relocation was part of a mass exodus, which Hwang's family was also a part of.

In Busan, Hwang was presented with the sound and sight of the 12-stringed gayageum for the first time. With only a grade school background in choir, he had never heard nor seen the zither-like instrument, except in pictures in a history class, and had believed the instrument to be extinct. He fell in love. 'I thought that I could hear the voice of our forefathers through the music,' he told Arirang TV in 2015. 'Those voices were saying, 'Why are you straying? Your place is here.'

While the center was focused mainly on Confucian ceremonial music, established folk musicians like the famous improviser Sim San-geon (1889-1965) also passed through. One day in 1951, Sim appeared at the old, two-storey wooden library where the center was located to perform sanjo, Korea's fundamental virtuosic instrumental repertoire (often translated into English as 'scattered melodies'). Hwang, transfixed, began studying with the man who accompanied Sim on drum that day, Kim Yun-deok (1918-1978), who played a school of sanjo that Hwang himself later inherited and eventually used as the basis of his own school of sanjo, which he published as a score in 1998, and added an accompanying CD in 2014, his final recording.

After the war, in 1955, Hwang moved back to Seoul and entered the law school at Seoul National University (SNU). There he met his wife, the already established author Han Mal-sook. The first department of Korean music was founded at SNU in 1959, just as Hwang was about to graduate; he was invited to become one of its first lecturers. When no students applied for the program, they recruited students from the department of music — that is, western music.

Helped re-establish gugak in post-war societyBy this time, traditional music, which would later be called gugak, 'national music,' had come to occupy so tenuous a place in devastated post-war Korean society that the only association with the word 'music' was western music. To make traditional music accessible to these students of 'music,' Hwang began transcribing sanjo onto the five-lined stave, publishing the first 'score' of sanjo in 1962. This started a process of fixing the ostensibly improvised oral tradition into written schools, almost transforming sanjo into 'works' in the western Romantic sense.

Hwang taught at SNU for four years before moving to Ewha Woman's University, where he stayed until 2001. There, he helped establish the third gugak department in Korea and the first advanced degrees in gayageum performance. Two of Hwang's top disciples, Yi Ji-young and Ji Ae-ri, were the first graduates of the doctoral program.

As a performer, Hwang eventually made it to Carnegie Hall in 1986; he also taught at Harvard in 1985. But these and a long list of national accolades are not likely to be what he is best remembered for. Hasan Hujairi pointed out just before Hwang's passing, '[Hwang] played an important role in championing visionary creators from other fields, including the Fluxus artist Paik Nam-june, and Hong Sin-cha, the mother of contemporary Korean dance. The influence of his musical aesthetic and his approach to presenting conceptual works was undeniable in the development of modern approaches to Korean traditional music over the past half-century.'

Composing for the gayageumOnly 11 years after he started playing gayageum, Hwang started composing, ushering in a new genre of music known as changjak gugak ('newly-composed Korean traditional music'). As he explained in 2016: 'In former times there was no concept of a composer or composition . . . music was not 'owned' by anyone, so no one put their name to a composition . . . I am the first who composed for the gayageum by using written manuscripts and western notation. My colleagues were surprised and probably a little embarrassed.'

As Hwang explained on Arirang TV in 2015, 'Tradition is about preserving customs. But if you only protect customs without introducing anything new, those traditions become merely antiques. . . . One thing I've learned from [western music and art] that really struck me is that you should never imitate others. So, from the start, I was determined to never imitate western music. I wanted to simply express what I felt in my soul . . . I try to create music that's like fresh spring water from a mountain.'

Hwang's music pleased not just the ear but the mind. In his most famous piece, 'Chimhyangmu,' or "Dance in the Fragrance of Agarwood' (1974), he portrays abstract ideas such as scents, colors, moods, images, and feelings with clarity, simplicity, and elegance, drawing on his early training in the dual traditions of folk and court music.

Hwang provided a new repertoire for an entire generation — a generation of players that has expanded almost exponentially. When Hwang started to learn gayageum in the 1950s, only 12 gayageum were sold per year. In 2015, 10,000 were sold.

For Hwang, the fact that the gayageum, once near extinction, eventually not only survived, but thrived, defined success.

The director of the National Gugak Center (1986-1993), Yi Seung-nyeol, summed up Hwang's essential qualities when he wrote, 'Hwang Byung-ki is a matchless musician who has inaugurated a new era . . . His music always has a naturalness and savor that springs from his experience of life. Not only does he combine elegance with logic, but his outstanding intuition and willingness to face reality exists alongside a Daoist bent like that of an unworldly immortal, and this cannot fail to have a strong appeal. There is no doubt that he will be remembered as one of the greatest musicians of our time.'

Hwang Byung-ki is survived by his wife, Han Mal-sook; his daughters Hwang Hye-kyung and Hwang Sook-yung; and his sons Hwang Jun-muk and Hwang Won-muk.

Dr Jocelyn Clark, a professor at South Korea's Pai Chai University, met Hwang Byung-ki for the first time in 1992, when she arrived in South Korea on scholarship to study gayageum with Hwang's student at the National Gugak Center. Over the following years, she translated Hwang's papers, wrote liner notes for the first four of his re-released CDs on the C & L label, edited his writing in English, and studied his gayageum compositions under his guidance.

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment