Stereophonic: This Play About An Ailing Rock Band Is A Must-See Masterpiece

Suffice it to say that it does. The play is a masterpiece. A must-see by all accounts. The legendary 13 Tony Award nominations and smash-hit period on Broadway, followed by doubly-extended runs in London's West End (where I saw it) are fully deserved.

The play follows a group of musicians in their recording studio in late-1970s California putting together an album that, once again, is expressly not Fleetwood Mac's Rumours. For a play that is about a band on the verge of titanic artistic, critical and popular success, the principal theme of the work is failure. Or rather, how to learn and grow from it: how to cut a great track; when to cut and run from a toxic relationship; what to keep or cut from our chequered lives so that we can carry on living.

Some of their rock-star lives seem like a lot of fun, but this really is play about work. The work of music and the work of life itself. Sure, the office might not be cubicles and water coolers. It is more like chez longues and gigantic communal bags of the cocaine (probably the hardest working prop currently on the London stage). Yet this is office politics all the same.

Writer Adjmi's brilliance is that, for all their rockstar antics, the band in Stereophonic are genuinely labouring for the execution of their vision. At the expense of the health and wellbeing. The beleaguered recording engineer, Grover (Eli Gelb), is in almost every scene working tirelessly at the recording desk. He is the Sisyphus of the soundcheck.

A trailer for Stereophonic.

The physical mass of the recording desk placed centre stage takes up much of the space typically reserved for the cast. They teeter tipsily around it. It recalls the omnipresence of the tape recorder driving Samuel Beckett's play Krapp's Last Tape (1958), a work with which Stereophonic has a surprising amount in common. Like Beckett, Adjmi is using recording technology to ruminate on the problem of time, which is where the play transcends its immediate setting and becomes most salient and meaningful.

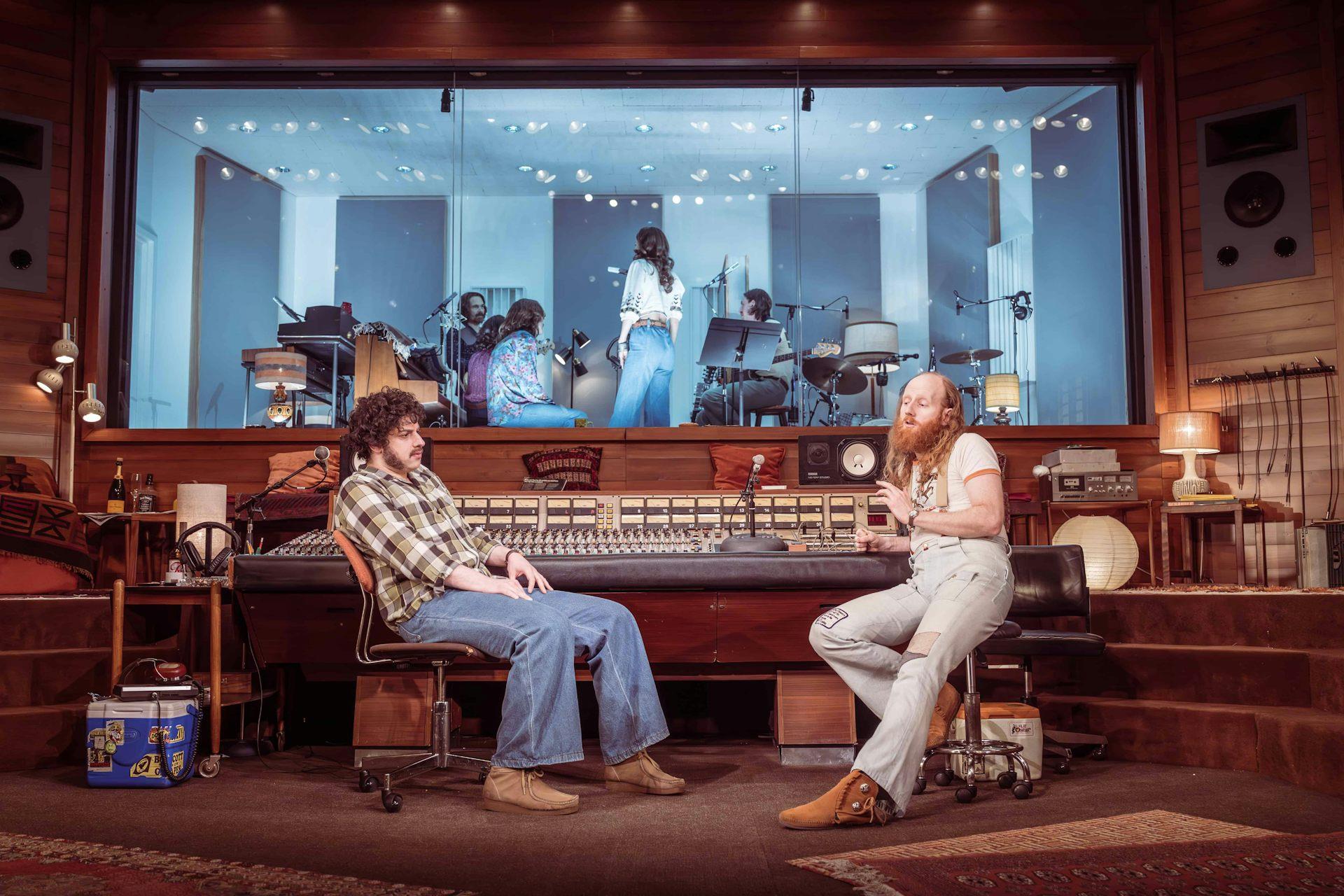

The stage is split in half with upstage placed behind a glass screen. We can sometimes hear behind it and sometimes cannot. It is a wall. But it is also a stage of its own on which the characters perform. As a metaphor, the staging stands for how in their relentless rock theatricality the characters can't always communicate. It asks, when does image or spectacle overtake the truth art seeks to reveal to the world?

All this (70s rock bands, heaps of cocaine, beige upholstery, unimpeded sexual license) could be put down to our cultural moment's obsession with nostalgia – a sign of our being stuck politically and socially. But that would be to miss the point of Stereophonic wholly.

The London theatre scene is awash with jukebox musicals with ropey plots built around forcing famous songs into some weak narrative. These are mostly not musicals so much as tribute acts forced to do skits. Stereophonic channels the nostalgia in a different direction. The songs are not actual Fleetwood Mac songs – but so good is Will Butler's (of Arcade Fire) score that they could be.

Action takes place both in the booth and the studio. Marc Brenner

Some of the performances (really performed live by the actors) just soar. This is a nostalgia that does not dwell in the past alone but is pointing forward. It is more like what the late, great critical theorist (following Jacques Derrida) Mark Fisher called “hauntology”.

As the characters disappear from downstage to appear behind the glass wall of the recording booth, this ghostliness is referenced directly. The recording booth makes the actors unreachable. But so does fame and the process of becoming legend. When one of them speaks into the mic it is like someone communicating through the void from the other side.

What makes classic rock so appealing, and such a great subject for a play, is partly the bildungsroman (fiction focused on the growth and development of young people) and crisis central to its story. It's almost religious. There was no autotuning available to them. There's no possibility of endlessly recording and recording over. They try to do this, but there are material limits to their endeavours. They have to get it right.

Adjmi's script suggests that magnetic tape and goodwill can, like a record label's patience, like our youth itself, run out suddenly and painfully. One day all this hedonism and earthly pleasure will end for them. As it will for us all.

When the label gives the band more time half way through, it is like they have been granted immortality or a stay of execution. Adjmi manages to make the whole enterprise feel as high stakes as a family tragedy.

Indeed, family (found or otherwise) looms large in the minds of the musicians. Singer Holly and bassist Reg's marriage is breaking down, drummer Simon misses the kids he has neglected for a year recording and boozing in Los Angeles, singer and guitarist Peter reveals the origin of his perfectionism in a conflict with his Olympic-swimmer brother.

The script works by transforming the musicians' meaningless, very stoned, profusions of words into moments of sudden beauty and clarity. Their druggy murmurings come suddenly to resemble a stunning lyrical murmuration of form and idea.

This technique replays in microcosm the play's engagement with the surprising human process of discovery and, let's call it, genius, that happens within the fold of limited mortal time. This is not just a play about rock. It is so much more.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment