(MENAFN- Asia Times) JEJU CITY – South Korea's Jeju is used to bouncing back from disasters. Not only has it weathered Covid-19, it survived the virtually overnight cut-off of its major tourism source when Chinese travel groups suddenly stopped arriving.

''We have learned that we need to build resilience to adapt and respond to impacts and changes due to external situations,'' said Jeju Governor Won Hee-ryong.

Indeed, this sub-tropical island 60 miles south of the Korean mainland and a one-hour's flight from Seoul is used to re-inventing itself.

As a tourism destination that has gone through three very different iterations, it has most recently upped sophistication while downsizing scale. Despite being the southernmost footprint of a nation notorious for its frenetic lifestyle, it has taken its foot off the accelerator and turned down the volume, becoming a center for a millennial format of introspective, eco-friendly tourism that favors quality, aesthetics and a genteel pace.

For the wider region, as tourism operators start to dust off facilities as the developed world vaccinates and wakes up from Covid-19, Jeju may provide a benchmark for rebooting.

Fishing boats at their moorings on Jeju's northwest coast. Photo: Asia Times / Andrew Salmon

Chill Jeju

With a population of 695,000 and an area of 1,850 square kilometers, Jeju is ringed by a plethora of palm-lined beaches that, in the summer, offer the full gamut of watersports. The island's beaches – and its water temperatures and its underwater scenery – don''t compare with those of Hawaii or Bali's, but its landscape and climate is varied.

The island's interior – dominated by the forested slopes and clouded heights of the dormant volcano of Mount Halla – is both rugged and beautiful, reminiscent of the Scottish highlands.

It is famed for its elderly female free divers, or haenyo, for the black stone that provides its primary building material and the ever-present wind from the sea. Its cuisine boasts seafood, black pork and citrus fruit.

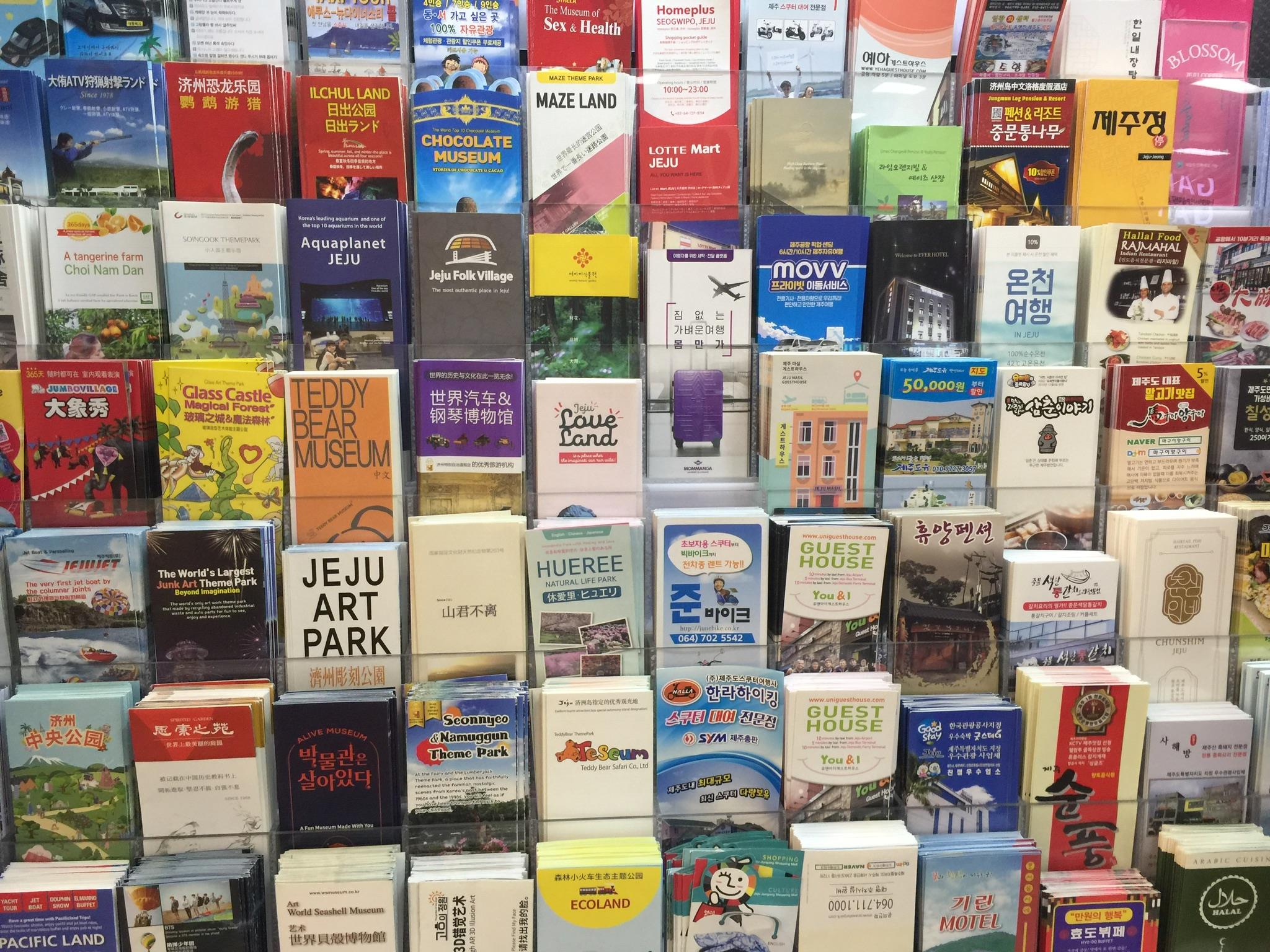

It boasts all the standard tourism fare with major hotel resorts, conference facilities and condos, backed by multiple attractions that range from a sex museum to art galleries to a shooting range to 30 golf courses.

But in recent years it has played host to a burgeoning number of smaller, lower-key, more aesthetically pleasing – and frankly hipper – facilities. Artisinal coffee roasteries, boutique guesthouses, craft-brew pubs and contemporary art galleries are the new norm – many owner-operated.

Some are designed by world-renowned architects, while others are based on traditional Jeju architecture. In all, aesthetics are at a premium.

When it comes to services, there are new bespoke operations, ranging from ''dark history'' briefings to environmental cleanups and yoga courses.

The foot is off the accelerator; the focus is on a slowed-down, laid-back lifestyle. The tilt is toward a demographic that seeks a quieter experience than the surf blast of Bali, the party vibe of Ko Pha Ngan – or indeed, the palli palli (hurry, hurry) culture that dominates mainland South Korea.

''This is the new trend,'' Governor Won told foreign reporters this week. ''We have lots of tourism products that focus on the tourist him or herself – it is about identifying oneself.''

Jeju Governor Won Hee-ryong in front of an image of Jeju's landmark Mount Halla. Photo: Asia Times / Andrew Salmon

It is not only officialdom that is talking.

''Every time I come here, I''m impressed and feel it's new,'' said Lee Jin-sook, a housewife visiting from the mainland who spoke to Asia Times at Jeju Airport. ''It's so clean, so natural and it's quieter than before, so that even though I''m in Korea, I feel like I am abroad.''

It is not only South Koreans singing the island's praises.

''If I had a choice, I''d move there in a heartbeat,'' said Eric Moynihan, a Seoul-based Canadian entrepreneur and CEO of Magpie, one of South Korea's leading artisanal breweries, which makes beer and operates its flagship outlet on Jeju.

Moynihan and his wife usually spend summers on the island.

''We rent a house in the countryside and I get up in the morning and cycle down to the beach and get a coffee – it's great,'' he said. ''There is a very slow and casual lifestyle … you have a lot of headspace and a lot of time.''

But this is all new – very new.

Given Jeju's recent history of low-end, mass-market tourism, few destination mavens could ever have predicted that the South Korean island could be deemed sophisticated or laid back.

A weekday evening in Magpie Brewery's Bluebird pub in Jeju City. Photo: Asia Times / Andrew Salmon ''The Hawaii of Korea?'' Historically, the island, far from Seoul, was a place of exile. In 1948, it was visited by a horror that presaged the Korean War two years later. In response to a communist uprising, troops unleashed a merciless counterinsurgency campaign that laid waste to the island's interior and thousands were slaughtered.

For the following decades, Jeju slumbered as an offshore backwater, sustained by fishing and agriculture. It first embraced tourism when South Korea's middle class emerged. By the 1980s, it was established as the premier national honeymoon destination.

As such, it became a land of kitsch, overrun by newlyweds in matching his-''n-her outfits, staying in blocky hotels and condos. It won an informal, and inaccurate, sobriquet: ''The Hawaii of Korea.''

This might have worked for locals, but caused knotted brows among foreigners.

''The ''Korean Hawaii'' phrase does confuse lots of tourists,'' admitted Won. ''Jeju has four seasons – the summers are hot but the winters see snow on Mount Halla – and we have lots of rainy days.''

Dramatic skies and gorgeous landscapes scarred by old-school development. The latter style of building is no longer favored for Jeju's development. Photo: Asia Times / Andrew Salmon

After South Koreans were granted passports by their newly democratic government in 1989, they could travel to the real Hawaii – and countless other destinations across the planet. For locals, Jeju's virtues quickly evaporated.

One idea – to grant Jeju tax-free, financial hub status – went nowhere. Another idea – to turn it into an international educational hub – gained limited traction. The island found its second wind after ex-Korean War foes Beijing and Seoul re-established diplomatic relations in 1992.

With China's moneyed middle class rising, Jeju granted visa-free access to Chinese tourists. At a time when an aspirational ''Korean Wave'' of pop culture – pop, dramas, film – was washing across China, the timing was perfect.

They came in the millions. Island roads were overrun with tour buses racing shipments of Chinese from airport to hotel to attraction to duty-free stores. Becoming a service center for the bottomless supply of Chinese tourists looked like Jeju's future.

Then geopolitics intervened.

In 2017, US troops, with Seoul's permission, planted a THAAD anti-missile battery on South Korean soil. Beijing, angrily claiming the system's radars could snoop on strategic assets on Chinese soil – retaliated against Seoul.

In China, retail firm Lotte was targeted and K-pop and K-dramas disappeared from Chinese airwaves. Tourism, too, was weaponized. In South Korea, Chinese tour groups canceled trips.

Jeju was hammered. In 2016, 3,051,522 Chinese visited the island. In 2017, there were 747,986 – a 75% drop.

''It was a really big issue,'' said Won. ''The impact was quite serious, especially for tourism businesses that aimed at Chinese group tours. Many closed down.''

Yet remarkably, tourism revenues in 2017 saw a marginal increase, from 5.5 trillion won ($4.8 billion) the year before to 5.7 trillion won ($5 billion). Likewise, domestic tourist arrivals to Jeju increased by 10%, while Japanese tourism increased by 24.7%.

''Since we have not had the influx – the parking lots for all the big buses are sitting idle – it made Jeju accessible for locals,'' said Brenda Paik Sunoo, a Jeju resident.

''Now, it is quieter here,'' agreed a male South Korean traveler, who spoke to Asia Times at Jeju Airport. ''You don''t have to wait in queues to get into restrooms or duty-free shops.''

For some businesses, it was a bonanza.

''We saw a 100% increase in our business after THAAD as we did not market to Chinese – we marketed to Koreans and to foreigners,'' Magpie's Moynihan said. ''For a lot of younger businesses that wanted to make hip, cool spots that were laid back. That was the initial wave.''

That ''initial wave'' points to Jeju's salvation – which lay in overlooked trends underway within broader South Korean society.

Leaflets for tourists at Jeju Airport. Photo: Asia Times / Andrew Salmon

Low-key reinvention

A rising generation of youthful South Koreans, facing such social ills as a shortage of once-common white-collar career paths, as well as soaring home prices in and around Seoul, were seeking different life paths.

This coincided with a wave of venture capital, previously unknown in South Korea, being released to small-scale entrepreneurs under the Park Geun-hye (2013-2017) and Moon Jae-in (2017 to the present) administrations.

Oblivious to the Chinese tourists, tens of thousands of mainlanders migrated to Jeju to revel in the island's landscape and lifestyle. The country oversaw a ''migrant boom'' between 2014 and 2017, with about 10,000 mainlanders settling each year, according to the Jeju governor's office.

Many created family-run, non-franchise, bespoke businesses aimed at luring a very different type of tourist than the Chinese.

''Many of our friends are in their 40s, with young families, and they came here to start over, to get out of the rat race on the mainland,'' said Paik. ''The irony is they end up working really hard as a café or pension (guest house) is seasonal – but their kids are able to get all these outdoor experiences.''

The 70-something Paik is also a migrant.

A Korean-American photo-journalist and author, she and her Korean-American husband departed California, partly to escape racism and gun violence, in 2015. Though they had originally planned to jet back and forth, they found themselves deeply embedded in Jeju, and now spend the majority of their time on the island.

Its lures, Paik said, are its ocean and mountains, its farmland and seasons and its shamanism and spirituality.

''I spoke to a New Yorker recently and he said If he could retire and stay here, he would,'' she said. ''He said, ''I think it has the best food in the world – it is farm-to-table, accessible and cheap, and because of the crops and rotation, good organic food is there.''''

Yet Jeju is still millennial South Korea – which means there is no lack of overseas goods.

''Living here and being a consumer and American, we don''t feel we are lacking anything,'' she said. And with so many of the new investments being small in scale, there is always something new.

''There are all these pop-ups – and new cafes and pensions, new museums and galleries,'' said Paik.

Building smaller, building better

Paik lives in a converted traditional dolji, or Jeju stone house.

Visitors to South Korea are often disappointed to find so few traces of hanok, or traditional homes and Jeju is the only province where the traditional local architectural style is still common. A further traditional feature is black stone walls that still crisscross the island's fields.

This is all very different to Seoul, with its architecture of mighty scale and brutal ugliness defying the city's natural scenery. Al fresco experiences and rooftop or balcony views are almost unknown and it is more common to visit a basement bar than a rooftop.

Jeju is different. Once the visitor leaves behind the blah surroundings of Jeju City, terraces and views of ocean or mountains from the island's cafes, bars and restaurants are virtually de rigeur. Aesthetics, in both internal and external design, are at a premium.

Unsurprisingly, the island has lured some of South Korea's leading architects and designers.

One of the wooden houses in a village of six on Jeju, designed by Seoul architect Doojin Hwang. Photo: Doojin Hwang

''Jeju is getting more and more refined pieces of architecture,'' Hwang Doo-jin, who heads the Seoul-based practice named after himself, told Asia Times.

His most recent project on the island, to be completed this summer, is a village of six wood houses, all for private clients. While they are based on a similar design, each home is different in detail – no cookie-cutter has been employed. The overall aim was to blend with, rather than dominate, the landscape.

''It is a very reserved, refined design,'' Hwang said. ''It is a high-end development, but it is not flamboyant.''

Other architects are coming from further afield.

Tokyo-based Jo Nagasaka/Schemata Architects were retained by South Korean company Arario to undertake the ''invisible redevelopment'' of the run-down and partially abandoned Tapdong Market area in Jeju City.

This urban redevelopment project, overseen by Arario CEO Kim Chang-il – one of South Korea's most renowned art collectors – and project managed by Seoul-based company Millimeter Milligram, has bought cutting-edge boutique design to the island.

While preserving the area's original architectural framework, interiors have been extensively remodeled. Renovated buildings now include a museum, a rental bike shop, a bakery and a combined space that sells local products and design products, while also offering 13 rooms of hotel or rental accommodation. The project, which started in 2018, was completed in May 2020.

Ararario had earlier brought Magpie – originally established as a small-scale brewery in central Seoul in 2012 – to Jeju. ''We met the Arario team who were famous for their galleries, and they were looking for a beer partner,'' Moynihan said. ''It was serendipitous.''

Arario invested in Magpie, funding a full-sized production brewery in Jeju, as well as the Bluebird craft pub in Tapdong, in 2014.

These kinds of design-centric upmarket developments have proved impervious to the loss of Chinese tourists.

''In the past, lots of large Korean corporates invested, and recently, a lot of Chinese corporations invested, but now the trend of tourism is changing,'' Won said. ''We are changing the direction of Jeju.''

The d & department Jeju, a multi-used building in Jeju City's Tapdong Market district. Photo: Jo Nagasaka / Schemata Architects

Post-Covid Jeju

It seems to be working out.

The island's best year for tourism revenue was 2019, the same year it had its second-best year in tourism numbers with 15.2 million visitors, with 1.7 million coming from overseas. The best year was 2016, just before the THAAD controversy, when Jeju welcomed 15.8 million visitors, of whom 3.6 million were foreigners.

In 2019, the service sector accounted for 76% of the island's GDP, while marketing campaigns and direct flights bought in foreign tourists from Southeast Asia and Japan.

Then came 2020 and Covid-19.

As travel shriveled up, Jeju saw visitor numbers fall to 10.2 million – the same kind of numbers seen in 2013. But given the wipeouts suffered by other overseas resorts and areas – such as the European winter sports sector – last year's visitor numbers demonstrated Jeju's resilience as a destination for locals.

''Now that Koreans are trapped in Korea because of Covid, it is nice to see all these families coming from the mainland and really getting fresh air for a change,'' said Paik.

Looking forward, Won is leading the island further on its current trajectory.

''Rather than attract tourists using large facilities, we are focusing more on preserving the culture and environment,'' he continued. ''At the moment, no large-scale investments are ongoing.''

While a massive new Grand Hyatt – 38 floors spread over two towers containing 1,600 rooms – opened in December 2020, there has been public resistance to a second airport, outside the scenic second city in the island's south, Seogwipo.

Its future is uncertain. An appreciation of the situation by the Ministry of the Environment will be ''reviewed comprehensively to discuss the direction and schedule,'' government sources in Seoul told Asia Times.

Since the pandemic, 'staycations,'' outdoor travel, camping, ''glamping,'' nature and ecology have become the island's keywords. With South Koreans still unable to travel abroad due to a slow local vaccination campaign and quarantine restrictions for all incoming travelers, the flights Asia Times took to and from Jeju this week were full.

Won is also using high technology to create new tourism products and services – and Jeju is becoming a testbed for South Korea in areas including highly networked smart driving and renewable energy. These issues will be covered in Part II.

A green tea farm in Jeju's interior. Photo: Asia Times / Andrew SalmonMENAFN19062021000159011032ID1102307168