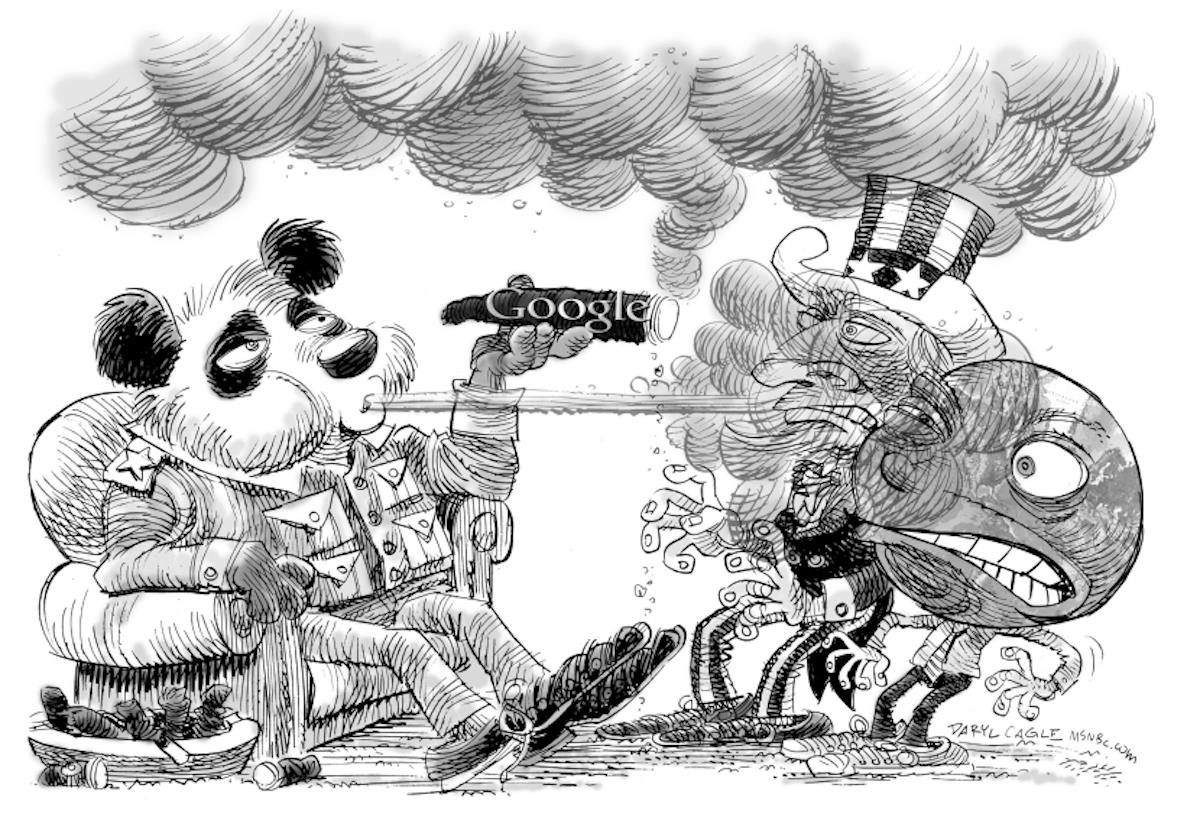

Trump Prefers Facing Weaklings But In Trade War China's Stronger

His meeting in Budapest with Vladimir Putin has been canceled, but even that setback is likely to be less disturbing to the American president's self-image as a supreme deal-maker than the encounter he is due to have in South Korea with China's President Xi Jinping on October 29 or 30. For America's trade war with China is intensifying and China holds the stronger hand.

There is a crucial difference between the way in which Trump must handle China and President Xi and the way in which he deals with all other political leaders, including Putin. With others, especially European leaders such as Emmanuel Macron, Sir Keir Starmer and Giorgia Meloni, he feels that he is strong and they are weak – because America has a strong economy and military, which they do not have. But with China he is dealing with a country that has as much power as he has and is not afraid to use it.

Bullies always prefer to fight weaklings rather than other bullies. Of course, Putin is a bully and is a master at flattering Trump, and no American president wants to risk getting into a nuclear war even with a weak Russia. But in the end, Trump knows that he holds tools with which he can pressure Putin if he chooses to. (He could revive his now-withdrawn threat – probably always hot air – to supply Ukraine with Tomahawk long-range cruise missiles.)

With China, it is Xi who holds the more powerful tools.

Latest stories

Trump pushing allies to buy US gas is a case of bad economics

BYD's EVs race ahead – but more established brands can catch up

Pakistan and the Afghan Taliban avoid a deeper war – for now

The trade war between the world's two largest economies (which, depending on how GDP is measured, make up a combined 40-45% of the world total) has been simmering ever since Trump imposed high tariffs on imports from China during his first term in office, to which China retaliated with its own tariffs. That trade war did not damage the rest of the world as it focused only on direct US-China trade, meaning that a lot of business was diverted by the tariffs to other countries.

The current trade war does, however, risk damaging the world economy as the battleground has moved from bilateral tariffs to export controls on critical minerals, on which producers all over the world depend.

The problem is one of dependency, but its origin lies in low costs and willingness to accept pollution. China's weapon is that it accounts for an estimated 70% of the world's mining of rare earths, minerals that are critical for magnets, batteries, semiconductors and other high technology and, even more importantly, it accounts for an estimated 90% of the processing of those minerals. Thanks to those economical supplies of minerals, it accounts for an estimated 93% of global manufacturing of advanced magnets.

So we are all highly dependent on Chinese suppliers, in both Europe and, crucially for the trade war, the United States. This dependency need not be permanent: These minerals are specialized but not scarce. However, mining and processing them is environmentally damaging and costly. That is why, in an open global market, buyers have chosen to obtain their supplies from China, where costs are low and environmental damage is more easily disregarded, rather than investing in new mines and processing factories in Europe, North America or elsewhere.

Step by step this year, China has announced that it is imposing controls on the export of these critical minerals, and this month has announced an extension of those controls to a wider range of minerals and even to products that contain small quantities of the minerals. These controls will apply to all countries, perhaps to make many of them annoyed at Trump for having caused this conflict.

Trump responded by threatening extra 100% tariffs on Chinese goods if the export controls are maintained. But pressure from American manufacturers is likely to make him back down. Their supply chains are too dependent on Chinese minerals for them to want to risk a lengthy blockade.

In truth, both sides will suffer if the US-China trade war escalates: American costs will rise, with some factories even risking closure; Chinese miners and manufacturers will lose export sales. The longer the export blockade lasts, the more investment will go into developing alternative supplies in Australia, Latin America or elsewhere, reducing China's long-term monopoly. So, some sort of truce is likely to emerge either from the Xi-Trump summit in Korea or shortly afterward.

The important point is not the specific outcome. It is that in this trade war we are witnessing a wrestling match between two equals, in which the rest of us are mere bystanders. China may not yet be America's equal as a military power, but in economic power it is.

Sign up for one of our free newsletters

-

The Daily Report

Start your day right with Asia Times' top stories

AT Weekly Report

A weekly roundup of Asia Times' most-read stories

That is why China is the only country that has proved willing to retaliate against Trump's tariffs in any serious way, because unlike the European Union it has the power to do so and is sufficiently resilient in political terms to be able to absorb the potential costs. Europe's politics are too fragile, as events in France demonstrate daily, and it needs America's support in Ukraine too much to risk a trade war.

If it emerges, a US-China trade truce will be good news. Nonetheless, we need to reflect on the potential implications of these two equals wrestling with each other and settling the fight through deals. One implication is that if China succeeds in using its export controls to force Trump to back down it may be tempted to flex its muscles in another area to test Trump's resolve, namely over the Philippines, Taiwan and control of the East and South China Seas. This could risk a dangerous military conflict.

Another implication, however, is that Trump might conclude that he needs to make concessions to his powerful Chinese counterpart, over the Philippines or more dramatically over the sovereignty of Taiwan, to serve American interests and his own personal interests. That could harm all countries that depend on the one-third of global trade that passes through the South China Sea.

Formerly editor-in-chief of The Economist, Bill Emmott is currently chairman of the Japan Society of the UK, the International Institute for Strategic Studies and the International Trade Institute.

Republished with permission, this is an updated version of the English original of an article published in Italian by La Stampa and in English on the Substac k Bill Emmott's Global View.

Sign up here to comment on Asia Times stories Or Sign in to an existing accounThank you for registering!

An account was already registered with this email. Please check your inbox for an authentication link.

-

Click to share on X (Opens in new window)

Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

LinkedI

Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

Faceboo

Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

WhatsAp

Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

Reddi

Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

Emai

Click to print (Opens in new window)

Prin

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Most popular stories

Market Reseach

- B2PRIME Strengthens Institutional Team's Growth With Appointment Of Lee Shmuel Goldfarb, Formerly Of Edgewater Markets

- BTCC Exchange Scores Big In TOKEN2049 With Interactive Basketball Booth And Viral Mascot Nakamon

- Ares Joins The Borderless.Xyz Network, Expanding Stablecoin Coverage Across South And Central America

- Primexbt Launches Stock Trading On Metatrader 5

- Solana's First Meta DEX Aggregator Titan Soft-Launches Platform

- Moonacy Protocol Will Sponsor And Participate In Blockchain Life 2025 In Dubai

- Primexbt Launches Instant Crypto-To-USD Exchange

Comments

No comment