US-South Korea Nuke Sub Pact Deeper Than It Seems

For the first time, Seoul will join an exclusive circle of nations able to operate nuclear-powered submarines, a capability previously limited to the US, UK, France, China, India and Australia under AUKUS.

Washington insists the transfer involves propulsion only, not nuclear weapons, but the strategic implication is nonetheless profound. Nuclear-powered boats can stay submerged for months, operate in near silence and patrol deep into contested waters. For South Korea, still technically at war with its northern neighbor, this is a transformational leap in deterrence.

The timing is no accident. Asia's maritime order is evolving faster than the alliances built to manage it. China's naval expansion has narrowed the US advantage in the Western Pacific.

Japan is revising its defense budgets and strategy, while Australia is retooling its fleet under AUKUS. North Korea's new generation of submarine-launched missiles and intercontinental systems further strains the region's deterrence balance.

By empowering Seoul, Washington is effectively decentralizing regional security – shifting from a single hegemon guarding the Pacific to a network of capable partners that can share the burden.

Latest stories

Space is America's next frontier, not EU's next bureaucracy

Odds surge Supreme Court will strike down Trump's tariffs

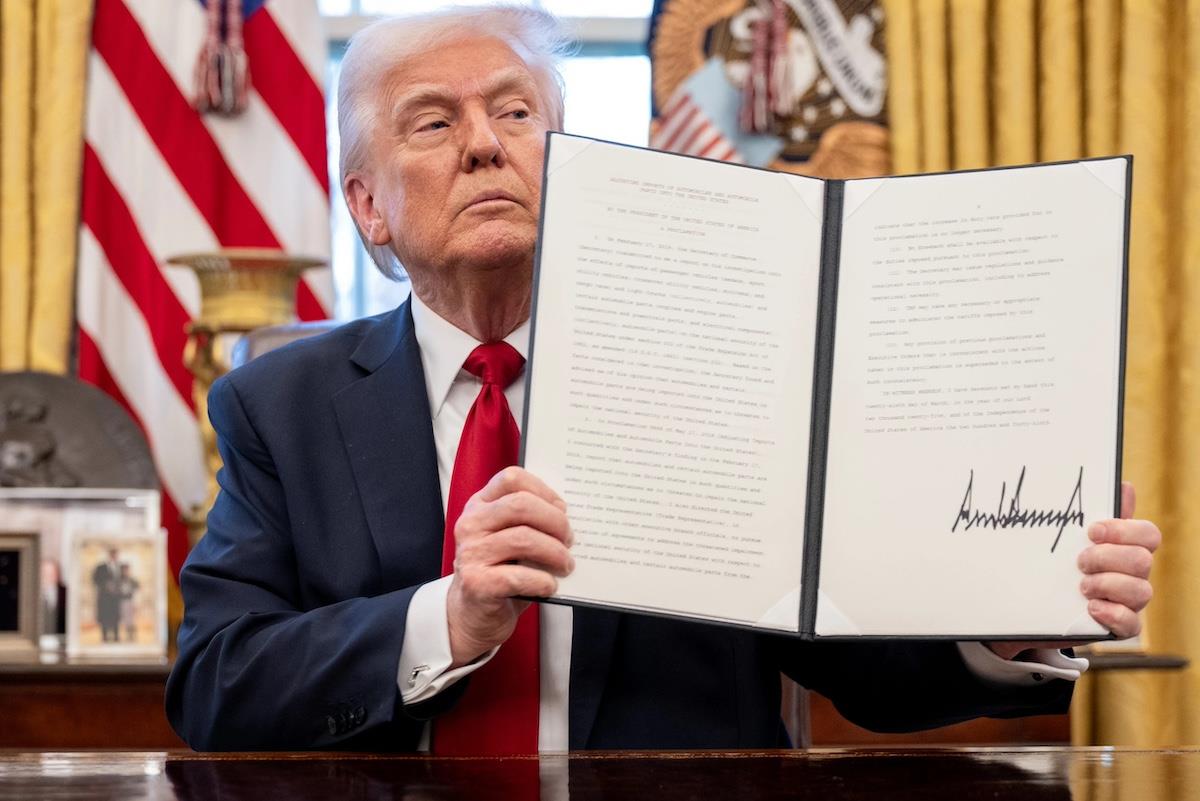

The mounting case against Donald Trump's tariffs

For Japan, this changes the arithmetic. Tokyo's own submarine fleet is among the world's most advanced, but it is conventionally not nuclear powered. The presence of nuclear-propelled South Korean vessels in nearby waters will inevitably spur debate about Japan's long-term posture.

While Japan's constitutional constraints make acquiring nuclear propulsion politically sensitive, the technological and strategic incentives are clear: longer-range patrols, integrated operations with US forces, and sustained under-sea awareness across the first and second island chains.

Beijing will read the Busan announcement as an extension of AUKUS principles. Its response will likely be twofold: accelerate its own undersea modernization and expand anti-submarine warfare capabilities in the East China and South China Seas.

Pyongyang, meanwhile, can be expected to claim justification for further missile and submarine tests. The result could be a new phase of silent competition beneath the waves, less visible than missile launches but no less destabilizing.

Yet the more intriguing upshot is political. The US move signals a readiness to share sensitive defense technology with trusted Asian partners – something Washington historically guarded tightly.

It marks a subtle evolution from containment to coalition: a region where capable allies act semi-independently while still aligned with US interests. In effect, it is an Indo-Pacific version of NATO's burden-sharing model, adapted for the Pacific's maritime theater.

This could certainly trigger an arms race. But expecting Washington alone to deter multiple threats reaching from the Korean Peninsula to the South China Sea is increasingly unrealistic.

A distributed security architecture, where Japan, South Korea, Australia and others possess complementary capabilities, may prove more sustainable than reliance on a single guarantor.

The economics are equally notable. South Korea's shipbuilding industry stands to gain from integrating nuclear propulsion systems, sensors and advanced materials.

Japanese suppliers, already world leaders in precision components, sonar arrays and reactor safety equipment, could become essential partners. If managed cooperatively, the deal could strengthen, rather than fragment, industrial ties among US allies.

For Tokyo, the challenge is to shape this new security environment, not merely adapt to it. The 2022 National Security Strategy envisioned Japan as a proactive stabilizer in the Indo-Pacific.

Sign up for one of our free newsletters

-

The Daily Report

Start your day right with Asia Times' top stories

AT Weekly Report

A weekly roundup of Asia Times' most-read stories

That role now requires deeper coordination with Seoul despite persistent historical tensions. Shared intelligence, anti-submarine drills and maritime de-confliction mechanisms would ensure complementarity rather than rivalry.

The Busan decision also underscores a larger truth: power in Asia is becoming more distributed – technologically, militarily and politically. A decade from now, the Indo-Pacific may look less like a US-led hierarchy and more like a constellation of strong middle powers capable of acting on their own.

For Japan, navigating that landscape will demand agility to defend its interests, maintain alliance credibility and preserve stability in seas that are growing busier and more contested by the day.

The US-South Korea nuclear submarine deal barely made front-page news, but its implications will surface soon enough. It marks not the end of American dominance but the rise of a shared maritime era – one in which Japan must decide whether to remain a cautious observer or a full architect of the Indo-Pacific's emerging new strategic order.

Sign up here to comment on Asia Times stories Or Sign in to an existing accounThank you for registering!

An account was already registered with this email. Please check your inbox for an authentication link.

-

Click to share on X (Opens in new window)

Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

LinkedI

Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

Faceboo

Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

WhatsAp

Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

Reddi

Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

Emai

Click to print (Opens in new window)

Prin

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment