How Rare Earths Became The Next Trade War Weapon

The US remains heavily dependent on China for rare earths, which are essential to defence, clean energy, and high-tech manufacturing. While the delay eases immediate pressure on industries reliant on rare earths, it should prompt a renewed focus on building alternative supply routes – from developing domestic mining, processing and refining capacity to strengthening partnerships with allied producers.

The trade-truce buys time, but lasting security will depend on reducing exposure to China's dominance in this critical sector.

Why are rare earths critical?Rare earth elements (REEs) - a group of 17 chemically related elements including neodymium, dysprosium, and terbium – are essential to the functioning of modern economies. Rare earths are key to everything from smartphones and wind turbines to EV motors and advanced military systems.

The 17 rare earth elements are typically grouped into light REEs (LREEs), including lanthanum, cerium, neodymium, praseodymium, which are used in magnets, batteries and catalysts, and heavy REEs (HREEs), which include dysprosium, terbium, yttrium – they are rarer, used in high-performance magnets, lasers, and alloys.

Rare earths in everyday technology

Source: ING Research

Rare earths are not actually rare, geologically speaking. For example, cerium is more abundant than copper. But although REEs are abundant in the Earth's crust, they are rarely found in concentrations suitable for economic extraction. Their chemical similarity makes separation complex and environmentally challenging.

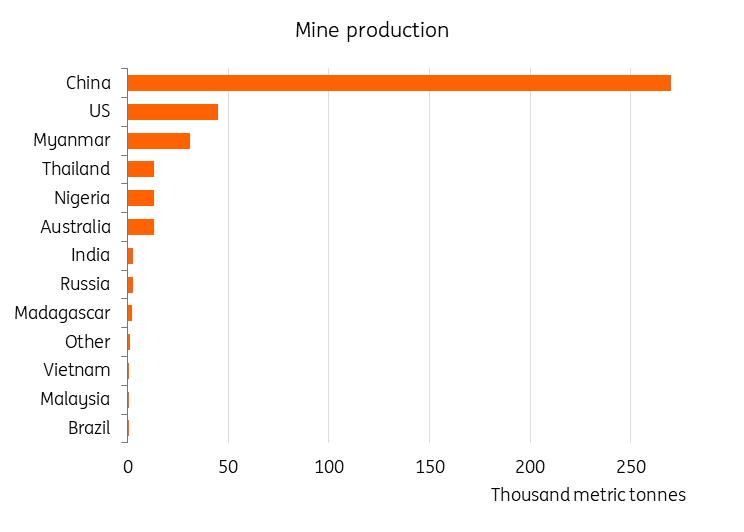

China dominates mined production of rare earths

Source: USGS, ING Research And it's home to almost half the world's reserves of rare earths

Data for Myanmar, Madagascar, Malaysia and Nigeria not available Source: USGS, ING Research China's dominance is decades in the making

The US was the world's top producer of rare earths until the 1980s, before China's dominance rose due to lower costs and government support for its rare earths industry.

China's dominance didn't happen overnight. Beginning in the 1980s, Beijing identified rare earths as a strategic industry, supporting development through subsidies, financing, favourable regulation and export controls.

By the 1990s, China had become the world's leading producer. Deng Xiaoping famously said in 1992:“The Middle East has its oil; China has rare earths”.

Today, China accounts for roughly 70% of global REE mine output, 90% of refining, and over 90% of magnet production.

Supply chain bottleneckThe rare earth supply chain is highly concentrated. Deposits exist outside of China, notably in Brazil, the US, and Australia, but many rely on Chinese refiners. It is refining capacity, rather than mineral wealth, that is the source of vulnerability.

Australia's Lynas Rare Earths is the world's largest supplier of rare earths outside of China; it relies on Malaysia for part of its refining.

Only two refineries exist outside China: one in the US and one in Malaysia.

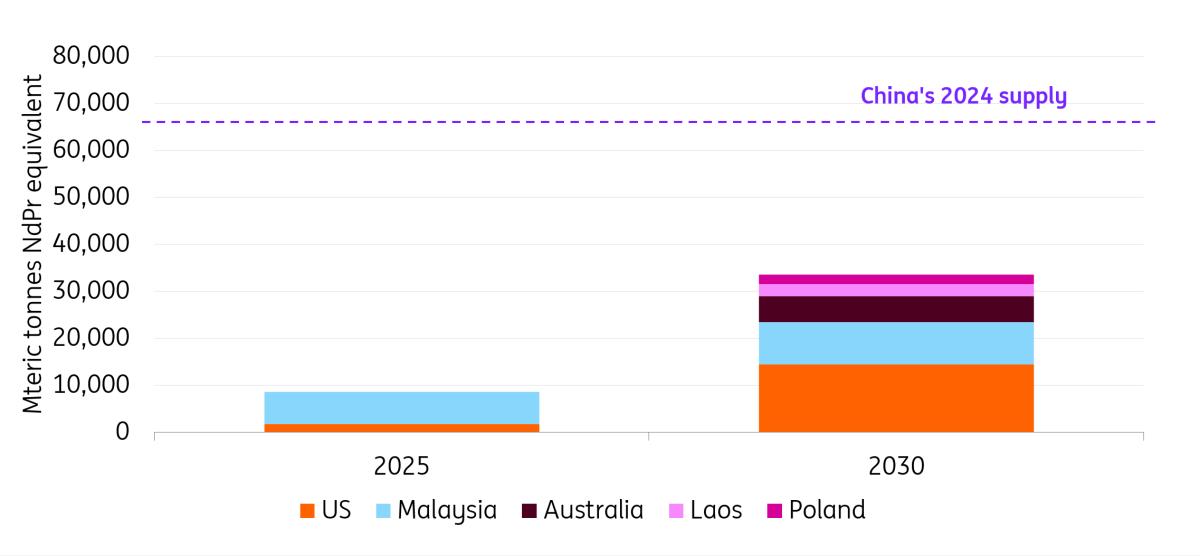

Global rare earths refined supply by region

Volume expressed as content of neodymium-praseodymium (NdPr) equivalent. China's supply figures were adjusted to match the production quotas and are just portions of total domestic capacity annually in the country Source: BNEF, ING Research

Scaling up remains slow due to high costs, technical complexity, and long permitting deadlines. Building a new mine can take eight to ten years, while building a new refinery takes about five.

Building mines, refineries, and processing plants in places like Australia, the US, and Europe also costs more because of higher capital needs, stricter environmental rules, and pricier labour and energy than in China.

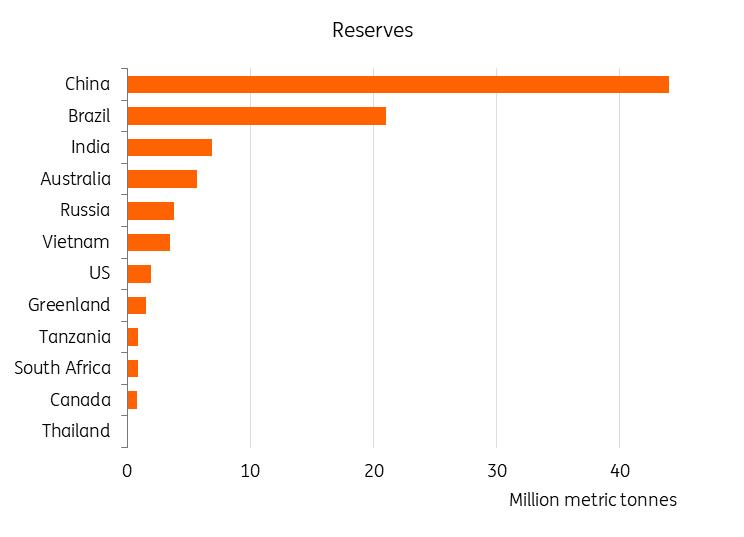

Even if the planned refineries outside China come online by 2030, total capacity will just be half of China's 2024 supply (according to BNEF data).

But without independent refining capacity, Western producers remain dependent on China.

Estimated rare earths refinery capacity growth outside of China

Note: Volume expressed as content of neodymium-praseodymium (NdPr) equivalent. China's supply figure for 2024 is adjusted to match production quotas and is not the total capacity available domestically in the country. Source: BNEF, ING Research How has Beijing used rare earths as a weapon in the trade war?

China has a history of using its dominance in the supply of rare earths as a pressure tool.

China's grip on the rare earths market became apparent in 2010 when it blocked exports to Japan for two months over a territorial dispute. The US, the European Union and Japan eventually forced Beijing to overturn the measures via the World Trade Organisation. The incident spurred Japan's efforts to reduce its reliance on China. Japan's dependence on China's rare earths dropped from around 90% at the time of the incident to around 60% today.

This year saw a significant escalation of China's rare earth restrictions as Beijing used its dominance over the critical materials to pressure the US administration.

In April, in response to escalating trade tensions, including US tariffs, Beijing imposed export restrictions on seven rare earths and permanent magnets, with companies needing to secure special licenses to send these materials overseas. The curbs included some heavy rare earths, which are almost exclusively produced by China. This was the first time China has placed rare earth magnets on the export control list.

The global automotive industry was among the sectors significantly affected by China's export controls on rare earth magnets. Ford Motor temporarily shut a Chicago factory in May after running short of rare-earth components. In the European Union, companies also reported several production stoppages.

Then, October saw sweeping new restrictions with Beijing outlining plans to expand curbs, including requiring overseas exporters of items that contain even small amounts of certain rare earths sourced from China to have an export license. It also subjected technology and equipment related to rare earths processing and magnets to export controls. These measures will now be suspended for a year. The original restrictions announced in April, targeting seven heavy rare earths, weren't addressed in the statement following this week's meeting between US President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping.

The US accounted for 10% of China's total rare earth exports in 2024, but restrictions have led to a 12% drop in shipments to the US from the first to the third quarter of 2025.

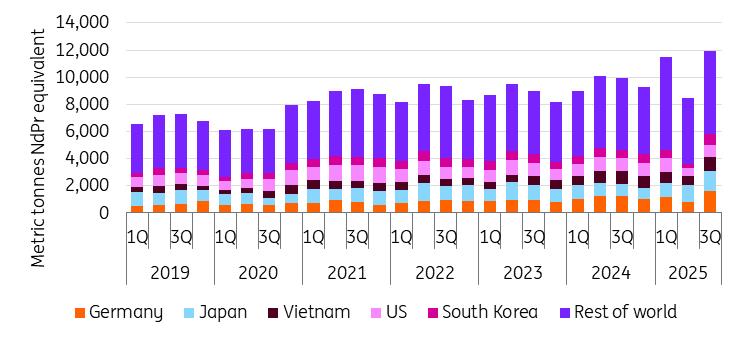

China total rare earth's exports volume by region

Volume expressed as content of neodymium-praseodymium (NdPr) equivalent to represent actual rare earths used in the end products exported. Source: China General Customs Administration, BNEF, ING Research Magnets drive China's rare earths exports

Source: China's General Administration of Customs, ING Research How will the US boost production of rare earths?

MP Materials operates the only American rare earths mine – Mountain Pass in California's Mojave Desert, reopened in 2018, and once the world's top supplier before production shifted to China. It received a $400 million investment from the Pentagon in July, which helped the company fund a new magnets plant in a deal that came with guaranteed purchases at minimum prices.

Trump is also looking beyond the US for rare earths supplies.

Earlier this month, the US and Australia agreed to jointly invest in Australian mines and processing projects. Both countries also pledged to protect their domestic markets from“unfair trade practices”, using trade measures like floor prices. Australia ranks fourth in rare earth reserves. Still, most projects are several years away from becoming operational.

The US President has also sealed a series of deals on his Asia trip to secure rare earth supplies, including deals with Japan, Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam and Cambodia.

The deal with Japan involves the two sides agreeing to boost the supply and production of rare earths, including plans for coordinated investment and stockpiling of rare earths. Meanwhile, Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam and Cambodia all agreed to increase US access to rare earths and export rules that would favour American buyers over Chinese companies. These include promises that they will not block shipments to the US. They would also encourage local processing and investment by non-Chinese firms.

These deals mark progress towards more diversified supply chains of rare earths, marking a shift in approach, increasing support and involvement from the state.

Rising demand adds urgencyThe rise in demand from EVs, renewable energy, and defence adds urgency to the market. The International Energy Agency (IEA) projects strong growth in rare earth demand driven by clean energy technologies. EVs are expected to lead, with a compound annual growth rate of 17.2% from 2024 to 2030, followed by wind turbines at 7.5%. Overall, rare earth demand is forecast to grow at 5.1% annually during this period. Other end uses include defence, mobile phones, displays, medical imaging, speakers, headphones, control rods in nuclear reactors and catalysts.

Rare earth demand is rising

Under the Stated Policies Scenario, covers only praseodymium, neodymium, terbium and dysprosium. Source: IEA, ING Research Loosening China's grip on rare earths won't be easy

The deal between Trump and Xi should not give policymakers a false sense of security. Instead, it must serve as a reminder that the United States urgently needs to accelerate efforts to build a supply chain for critical minerals and magnets that does not depend on China. Beijing's dominance means it can tighten export restrictions at any time.

In the near term, China will likely maintain its edge, thanks to technical expertise, low costs, and an extensive supply network. But rare earth supply chains must diversify. International cooperation and investment are essential first steps.

Breaking Beijing's grip on rare earths will be slow and expensive, but the payoff is strategic independence. Export controls that give China leverage today will ultimately spur global efforts to develop non-Chinese supply chains. The more the world invests in onshoring and alternative suppliers, the less control China will wield in the long run.

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment