(MENAFN- Asia Times) In early 2013, Cambodia's long-serving opposition figurehead Sam Rainsy made a whirlwind tour of Southeast Asia.

He first visited fellow pro-democracy icon Anwar Ibrahim, the leader of Malaysia's opposition, then darted off to Yangon for a meeting with Aung San Suu Kyi, the Nobel Peace Prize laureate who had only been released from house arrest a few years earlier.

“The three of us, as opposition leaders of three ASEAN countries, should work together to promote democracy in our region,” Rainsy said after their meetings. For a few years, it appeared they were on the cusp of real change.

Today, however, the fortunes of Southeast Asia's three pro-democracy icons have imploded. Rainsy has been in self-exile since late 2015, Suu Kyi is now once again under house arrest and Anwar faces calls to retire as the leader of Malaysia's opposition coalition.

“Southeast Asia's pro-democracy icons have reminded us time and again that those pro-democracy beliefs may prove ephemeral,” said Thomas Pepinsky, director of the Southeast Asia Program at Cornell University.

“Although disappointing, this should clarify that the real work of building democracy is building representative institutions that provide real accountability and electoral systems that provide real choice,” he said.

This was far from certain back in 2013 and 2014. Not only was their iconic status still burning bright in defiant opposition, it also appeared they might someday soon win power.

Rainsy, who was allowed to return from his second-stint in exile in 2013, saw his opposition Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP) almost defeat the long-ruling Cambodian People's Party at that year's general election, gaining only about 4 percentage points less than the ruling party in the popular vote.

Anwar and his Rakyat coalition won the popular vote in Malaysia's general election in 2013, though the ruling Barisan Nasional managed to claim victory in what was its worst electoral result in history.

A Burmese monk looks at a poster of Burma's pro-democracy leader Aung San Suu Kyi in Leicester Square underground station in London on June 15, 2000. Photo: AFP / Hugo Philpot

After Myanmar's military rulers started their transition toward more political openness in 2010, Suu Kyi's National League For Democracy (NLD) was all but certain to clinch an historic victory at the 2015 ballot, which it did, picking up 57% of the total vote, allowing Suu Kyi to become the country's new State Counsellor.

Even away from these three icons, other Southeast Asian pro-democracy figures became first among equals.

In Vietnam, famed lawyer Nguyen Van Dai was keeping alive the noble tradition of resistance against the Vietnamese Communist Party's authoritarian rule.

Having helped form the pro-democracy movement Bloc 8406 in 2006, seven years later he founded another movement, the Brotherhood for Democracy, that seemed historic in uniting the country's disparate reformist groups, from rural land-rights protesters, environmentalists and urban liberals.

Benigno Aquino III might have been considered a weak president since taking office in 2010, but more than most politicians, he appeared to represent the liberal tradition of the Philippines.

In Indonesia, newly-elected president Joko Widodo, who took office in October 2014, vowed to be the genuine voice of reform in the country, promising to lead an administration committed to human rights and progressive policies.

Former Thai prime ministers Thaksin Shinawatra and his sister Yingluck in exile in 2018. Photo: AFP / Yasuhiro Sugimoto / Asahi Shimbun

The Shinawatra siblings still held political cache in Thailand, even after Yingluck's government was overthrown by a military coup in May 2014.

Yet that was the high-water mark of Southeast Asian democratic hopes. Rainsy has been in self-exile since late 2015 and his CNRP, the country's only viable opposition party, was forcibly dissolved two years later on spurious charges of plotting a US-backed coup.

Cambodia's long-ruling prime minister, Hun Sen, now appears to have cemented a de-facto one-party state.

In Malaysia, Anwar was once again jailed in 2015 for a second trumped-up sodomy conviction, although while in jail he claimed some success when his Pakatan Harapan coalition won the 2018 election, removing the dominant United Malays National Organization (UNMO) from power for the first time in the country's history.

But any ambitions Anwar had of becoming prime minister faded as Mahathir Mohamad, a former premier under an UMNO government, snatched the top job. Despite a tacit promise that he would one day step down to allow Anwar to become prime minister, Mahathir's government fell earlier this year and Anwar's opposition coalition failed to find new allies to form a government.

Oh Ei Sun, of the Singapore Institute of International Affairs, argued last month that Anwar was now a major stumbling block if the opposition Pakatan Harapan coalition wanted to expand.

“Anwar has to step down because his appeal as a leader is waning,” Sun was quoted as saying in Free Malaysia Today, a local newspaper.

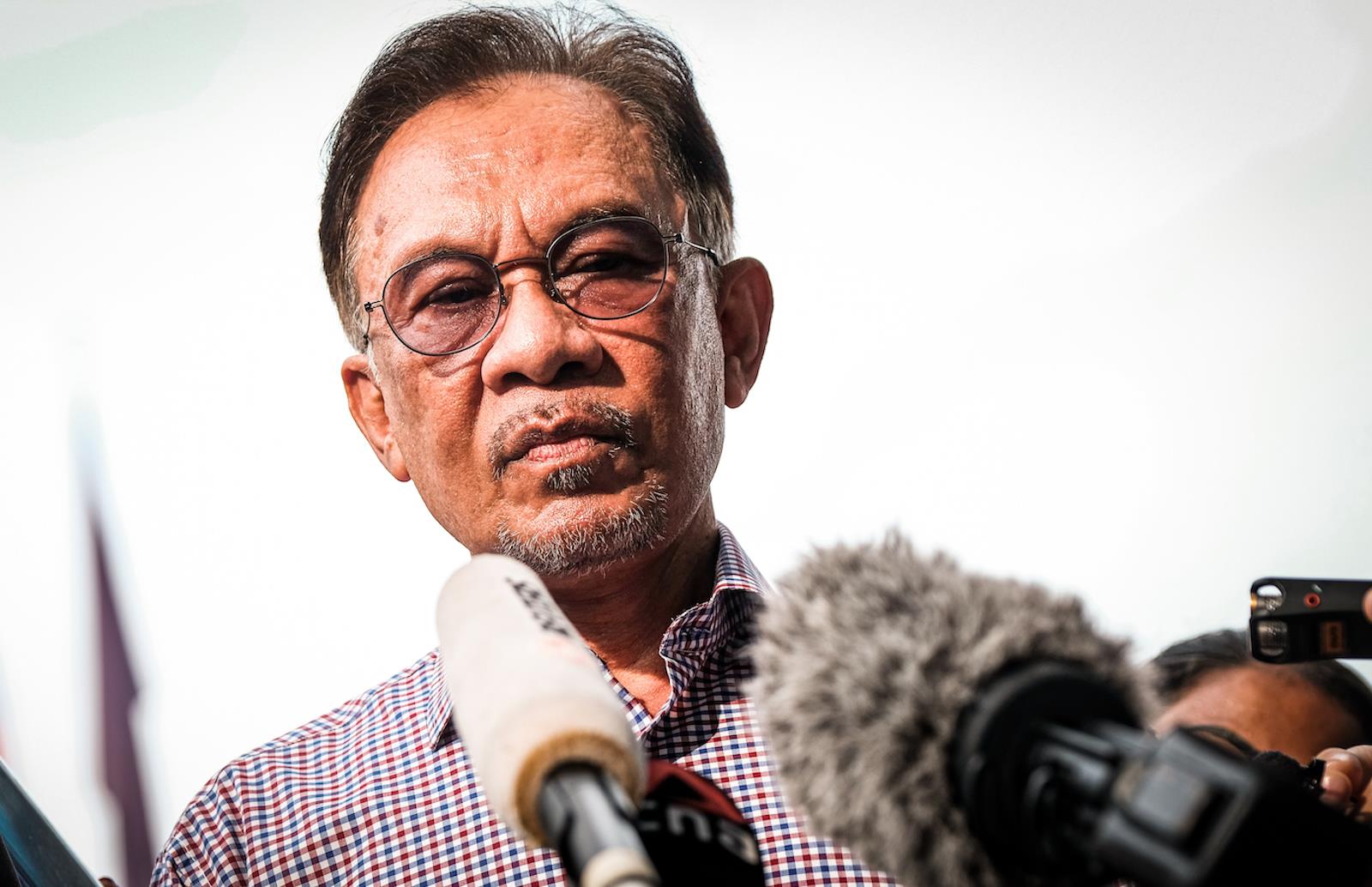

Anwar Ibrahim, a leading figure in Malaysia's opposition. Photo: AFP / Syaiful Redzuan / Anadolu Agency

Benigno Aquino III is seldom remembered at all today and, when he is, it is usually to ask how his presidency became the gateway for his successor, Rodrigo Duterte. President Widodo has mostly disappointed those who believed he would be the beacon for Indonesian reform. Vietnam's Nguyen Van Dai was arrested in December 2015 and was released three years later, only to be sent off into exile in Germany.

Thanathorn Juangroongruangkit took up the Shinawatra sibling's mantle as the liberal Thai alternative and he might have overturned the military's rule at the 2019 ballot, but post-election ploys by Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha saw Thanathorn's Future Forward party dissolved.

Although still advocating for democratic change, Thanathorn has been squeezed into virtual silence by criminal charges, including those of lese majeste.

Arguably the greatest fall of any of the icons was Suu Kyi, whose NLD civilian government was ousted by a military coup on February 1. She has been under house arrest since the putsch on charges of sedition and corruption, as well as other questionable charges.

Although Suu Kyi and her NLD won last year's general election by a handsome margin, it has been quite some time since she was spoken of internationally as a pro-democracy icon, let alone as a beacon for liberalism in the region.

She governed during the Rohingya genocide and, though she was not directly to blame for the atrocities, she was accused of lying about the human rights violations and adding to the anti-Muslim rhetoric fuelling the genocide.

Aung San Suu Kyi with Myanmar military chief Min Aung Hlaing in Naypyidaw in March 30, 2016. The Military has again put her under arrest. Photo: Reuters / Ye Aung Thu

Her own government, which ruled between 2016 and the coup in February this year, has also been accused of repressing free speech and failing to implement meaningful reform. An essay published by the Guardian in 2018 about Suu Kyi's fall from grace was headlined:“From peace icon to pariah.”

“The personality and public commitment to liberal democracy of these icons have undoubtedly inspired millions in their countries and around the world,” said Pepinsky, of Cornell University.

“But it is essential to remember that democracy is a system, not a set of values espoused by leaders,” he added.“We are bound to be disappointed if we pin our hopes in democracy on the values or beliefs of one or two major politicians.”

Indeed, once authoritarian-minded governments removed the leaders of the movements, such as Rainsy in Cambodia and Suu Kyi in Myanmar, their entire pro-democracy movements crumbled around them.

Indeed, it is questionable whether the pro-democracy parties can even exist without their icons. In Myanmar, Suu Kyi's status was so integral to the NLD's popularity that it became unclear whether millions of Burmese voters were voting for her or the party.

Between 1998 and 2012, Cambodia's main opposition party was officially called the Sam Rainsy Party until it merged in 2012 to form the CNRP with the Human Rights Party, led by another Cambodian political icon, Kem Sokha.

Other pundits note the age of Southeast Asia's pro-democracy icons. Suu Kyi is 76, Rainsy is 72 and Anwar 74. Not only are they many decades older than the average age of their country's population, but the septuagenarians have also been accused of preventing younger pro-democracy figures from rising to the top.

“I personally think it does tarnish democracy a bit, since in some of those cases democracy was so personally identified with the individual, and perhaps too personally identified for sure,” said Joshua Kurlantzick, senior fellow for Southeast Asia at the Council on Foreign Relations.

“I think there are many broader forces, and the issues with these figures is not the biggest reason why democracy is failing,” he added.“But it may be a reason on the margins.”

James Chin, director of the Asia Institute at the University of Tasmania, noted that democracy around the world, not only in Southeast Asia, has worsened over the past few years.

Freedom House's index has ranked Southeast Asia's democratic standards as having deteriorated considerably in the latter half of the 2010s.

But a lot of the region's pro-democracy symbols are still political icons in their own countries, Chin said, adding that their waning status is more of an international perception, driven either by their apparent failings to properly stand up for democratic interests or their inability to gain power.

On January 4, 1997, then Myanmar opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi addressing a gathering of supporters at her Yangon residential compound to mark the 49th anniversary of the country's independence movement. Photo: AFP / David Van Der Veen

“Aung San Suu Kyi was an iconic human rights victim. She won the Nobel Peace Prize for it. She was a horrible human rights defender. Ask the Rohingya. Now she's back to being a human rights victim, but the gleam has faded,” Kenneth Roth, executive director of Human Rights Watch, tweeted not long after the February 1 coup.

Suu Kyi has faced a considerable international backlash since 2017 over allegedly turning a blind eye to a“genocide” going on in her country. Dozens of universities and institutes across the world revoked her awards and honorary titles.

Nonetheless, within Myanmar her NLD won last year's general election by a very handsome margin, picking up 258 of the 330-elected seats in the House of Representatives, the country's lower house.

For the international community, the decline of Southeast Asia's pro-democracy icons appears to have affected policy. One reason Western governments have not taken such an assertive stance against the February 1 military coup in Myanmar is because they fell out of love with Suu Kyi and her NLD government, analysts have said.

And it would appear that there no longer any real belief in Washington or Brussels that Rainsy nor Cambodia's opposition CNRP can return to politics, meaning Western pressure against Prime Minister Hun Sen's regime has been scaled back over the past two years.

On the one hand, it is difficult to imagine the successes of Southeast Asia's pro-democracy movements without the leadership of the political icons. On the other hand, their prominence has made their movements top-heavy, too insensitive to the demands of grassroots supporters and easily destructible.

A problem with icon-worship is it allows people to express their political desires vicariously through the life of one person, providing a tempting belief that it is people and their passions that change society, not slow and complex structural change.

Perhaps, also, the outside world was too quick to accept their iconic status, to judge their actions and words by their reputations, and not the other way around.

The late journalist Christopher Hitchens once wrote:“The rich world likes and wishes to believe that someone, somewhere, is doing something for the third world. For this reason, it does not inquire too closely into the motives or practices of anyone who fulfills, however vicariously, this mandate.”

MENAFN09102021000159011032ID1102942628