Politicians Bank On People Not Caring About Democracy But Research Shows We Do

Increasingly, people feel politics is something done to them, not with them or for them. Many believe the system no longer represents their interests or responds to their needs, and that it serves powerful actors rather than the public good.

Australian attitudes echo a broader global trend. People are increasingly questioning a model of democracy that reduces their role to voting every few years and leaving the rest to elected representatives. They're seeking deeper ways to contribute, especially on complex, long term issues, such as responses to the climate crisis.

This isn't a rejection of democracy as an ideal. It's a loss of faith in how democracy is being practised. People don't feel heard.

Surveys have recorded this frustration for several years. Yet they rarely ask the crucial follow up question: if people are unhappy with the way democracy is working, what changes do they want to see?

Our new report released today asks this question. Drawing on a nationally representative survey of 4,200 adults, it shows Australians don't want less democracy, they want a more meaningful one. They want democracy that listens, responds, and creates genuine opportunities between elections, for people to have a say in the decisions that shape their lives.

Democracy through discourseA common assumption is that people are too apathetic, distrustful, or busy to get involved in politics.

Our findings call this assumption into question.

We found strong support for a more“talk-centric” model of democracy. Nearly one in two Australians (48%) say the best way to make political decisions in a democracy is through dialogue with citizens and affected groups.

Only 9% think decisions should be left to elected representatives without public input.

On a similar note, Australians show more trust in their fellow citizens than is often assumed. More than a third (36%) say they would trust a group of everyday people, brought together to deliberate, to produce sound recommendations on their behalf.

This sort of initiative is called deliberative democracy. Rather than treating democracy mainly as a contest of votes, these processes complement elections by creating spaces for informed public discussion.

They bring together everyday people – often by random selection – to learn about an issue, hear from experts and stakeholders, deliberate with one another, and develop recommendations.

But would people actually be a part of it?Survey respondents showed a strong willingness to participate in these sorts of forums. When asked if they'd be likely to take part if invited, 56% said they would. This points to an unmet demand for more direct and meaningful ways to contribute

That demand was strongest among the people often written off as“disillusioned”. Among those dissatisfied with democracy, 63% said they would be willing to participate in a deliberative forum.

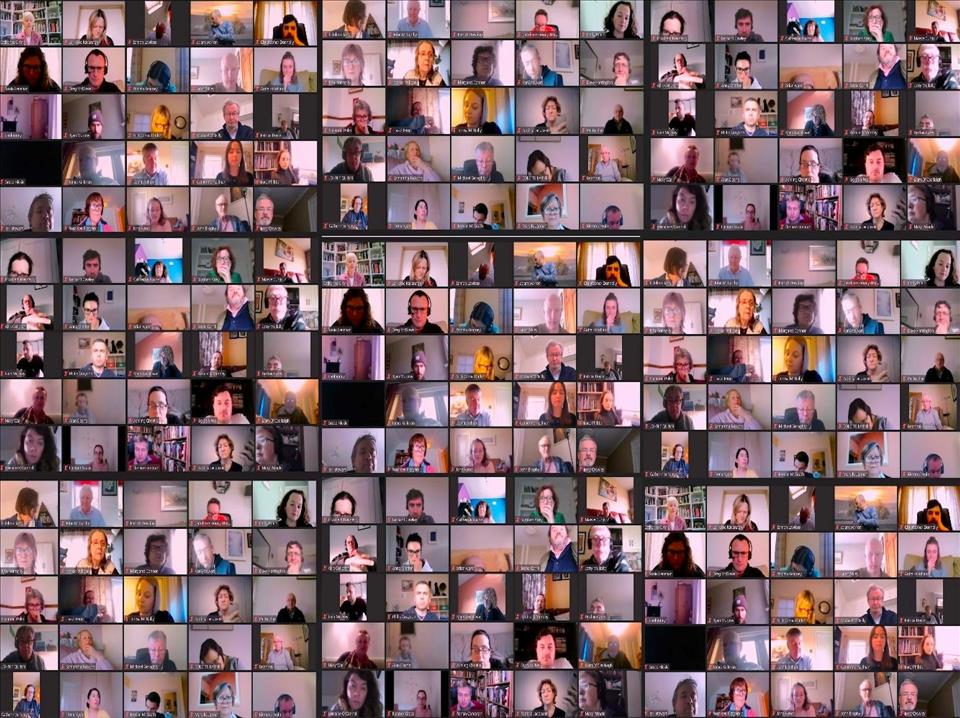

National deliberation on Housing organised by AMPLIFY in February 2025.

Among those who distrust government, the figure is 59%.

People also saw deliberative processes as a sign of good political leadership. More than half (54%) view deliberative forums as evidence politicians are responsive – that they value the ideas and experiences of ordinary people.

Who's standing in the way? PoliticiansSo given the public appetite, could deliberative democracy innovations work in Australia?

Australia already has a rich, if uneven, history of experimentation with deliberative engagement, particularly at the local and state level.

But at the national level, politics continues to rely mostly on elections and elite parliamentary deliberation.

By contrast, Ireland's national citizens' assemblies on issues from marriage equality to climate change show how deliberation can tackle complex and contested policy questions where legitimacy depends on structured public input.

Parliamentary committees and their inquiry processes also offer promising spaces to expand the opportunity and capacity of citizens to scrutinise parliamentary deliberations.

The main barrier to deliberative democratic reform is not citizen apathy. It is the reluctance of political elites – especially federal politicians – to trust citizens and to see them as capable partners in tackling hard problems.

Without that confidence, political leaders are unlikely to champion reforms that genuinely shift power towards the public, even when the evidence shows they can improve decision-making and legitimacy.

Promising signs for the futureThe Department of Home Affairs' recent Strengthening Australian Democracy report highlighted deliberative practices as one way to improve citizen engagement and democratic resilience.

The first national Guidebook for Deliberative Engagement, produced by the University of Canberra's Centre for Deliberative Democracy, was recently commissioned by the New South Wales and federal governments to support agencies across Australia in designing and running these processes effectively.

Australians are not calling for the replacement of elections or the discarding of representative institutions. They are asking for a democracy that listens between elections.

Delivering that will require political leadership willing to pilot, scale and normalise new ways for citizens and decision-makers to work together.

The public appetite is there. The question is whether our institutions and political actors are ready to catch up.

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment