'Digital Colonialism': How AI Companies Are Following The Playbook Of Empire

In fact, OpenAI and Google are arguing that a part of American copyright law, known as the“fair use doctrine”, legitimises this data theft. Ironically, OpenAI has also accused other AI giants of data scraping“its” intellectual property.

First Nations communities around the world are looking at these scenes with knowing familiarity. Long before the advent of AI, peoples, the land, and their knowledges were treated in a similar way – exploited by colonial powers for their own benefit.

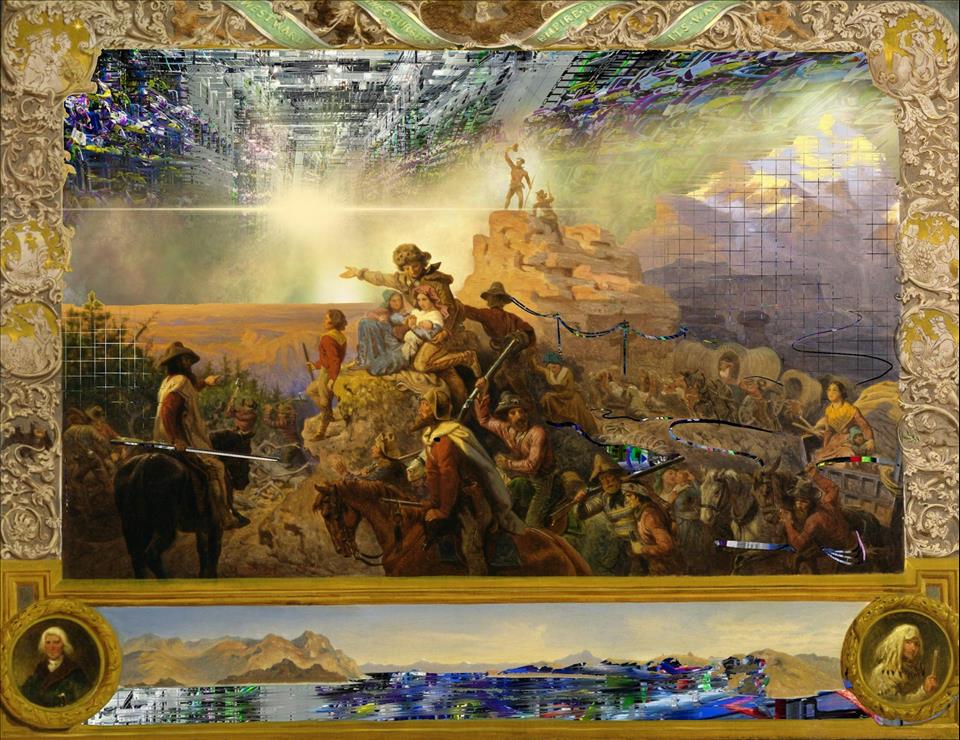

What's happening with AI is a kind of“digital colonialism”, in which powerful (mostly Western) tech giants are using algorithms, data and digital technologies to exert power over others, and take data without consent. But resistance is possible – and the long history of First Nations resistance demonstrates how people might go about it.

The fiction of terra nulliusTerra nullius is a Latin term that translates to“no one's land” or“land belonging to no one”. It was used by colonisers to“legally” – at least by the laws of the colonisers – lay claim to land.

The legal fiction of terra nullius in Australia was overturned in the landmark 1992 Mabo case. This case recognised the land rights of the Meriam peoples, First Nations of the Murray Islands, as well as the ongoing connection to land of First Nations peoples in Australia.

In doing so, it overturned terra nullius in a legal sense, leading to the Native Title Act 1993.

But we can see traces of the idea of terra nullius in the way AI companies are scraping billions of people's data from the internet.

It is as though they believe the data belongs to no one – similar to how the British wrongly believed the continent of Australia belonged to no one.

Digital colonialism dressed up as consentWhile data is scraped without our knowledge, a more insidious way digital colonialism materialises is in the coercive relinquishing of our data through bundled consent.

Have you had to click“accept all” after a required phone update or to access your bank account? Congratulations! You have made a Hobson's choice: in reality, the only option is to“agree”.

What would happen if you didn't tick“yes”, if you chose to reject this bundled consent? You might not be able to bank or use your phone. It's possible your healthcare might also suffer.

It might appear you have options. But if you don't tick“yes to all”, you're“choosing” social exclusion.

This approach isn't new. While terra nullius was a colonial strategy to claim resources and land, Hobson's choices are implemented as a means of assimilation into dominant cultural norms. Don't dress“professionally”? You won't get the job, or you'll lose the one you have.

Resisting digital terra nulliusSo, is assimilation our only choice?

No. In fact, generations of resistance teach us many ways to fight terra nullius and survive.

Since colonial invasion, First Nations communities have resisted colonialism, asserting over centuries that it“always was and always will be Aboriginal land”.

Resistance is needed at all levels of society – from the individual to local and global communities. First Nations communities' survival proclamations and protests can provide valuable direction – as the Mabo case showed – for challenging and changing legal doctrines that are used to claim knowledge.

Resistance is already happening, with waves of lawsuits alleging AI data scraping violates intellectual property laws. For example, in October, online platform Reddit sued AI start-up Perplexity for scraping copyrighted material to train its model.

In September, AI company Anthropic also settled a class action lawsuit launched by authors who argued the company took pirated copies of books to train its chatbot – to the tune of US$1.5 billion.

The rise of First Nations data sovereignty movements also offers a path forward. Here, data is owned and governed by local communities, with the agency to decide what, when and how data is used (and the right to refuse its use at any point) retained in these communities.

A data sovereign future could include elements of“continuity of consent” where data is stored only on the devices of the individual or community, and companies would need to request access to data every time they want to use it.

Community-governed changes to data consent processes and legalisation would allow communities – whether defined by culture, geography, jurisdiction, or shared interest – to collectively negotiate ongoing access to their data.

In doing so, our data would no longer be considered a digital terra nullius, and AI companies would be forced to affirm – through action – that data belongs to the people.

AI companies might seem all-powerful, like many colonial empires once did. But, as Pemulwuy and other First Nations warriors demonstrated, there are many ways to resist.

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment