Black Lungs And Broken Promises: The High Cost Of Breathing In Delhi

New Delhi: For most part of human civilization, the average life expectancy was dismal. Someone born in 1800 was not expected to live beyond thirty. A century later, by 1900, this number improved only marginally to 32 years. The largest increase came post 1950s, when life expectancy rose from a little over 46 years to 73 years by 2023. This dramatic rise in the length of human life was possibly because of multiple advancements in healthcare, access to vaccines, better nutrition and improvement of living standards.

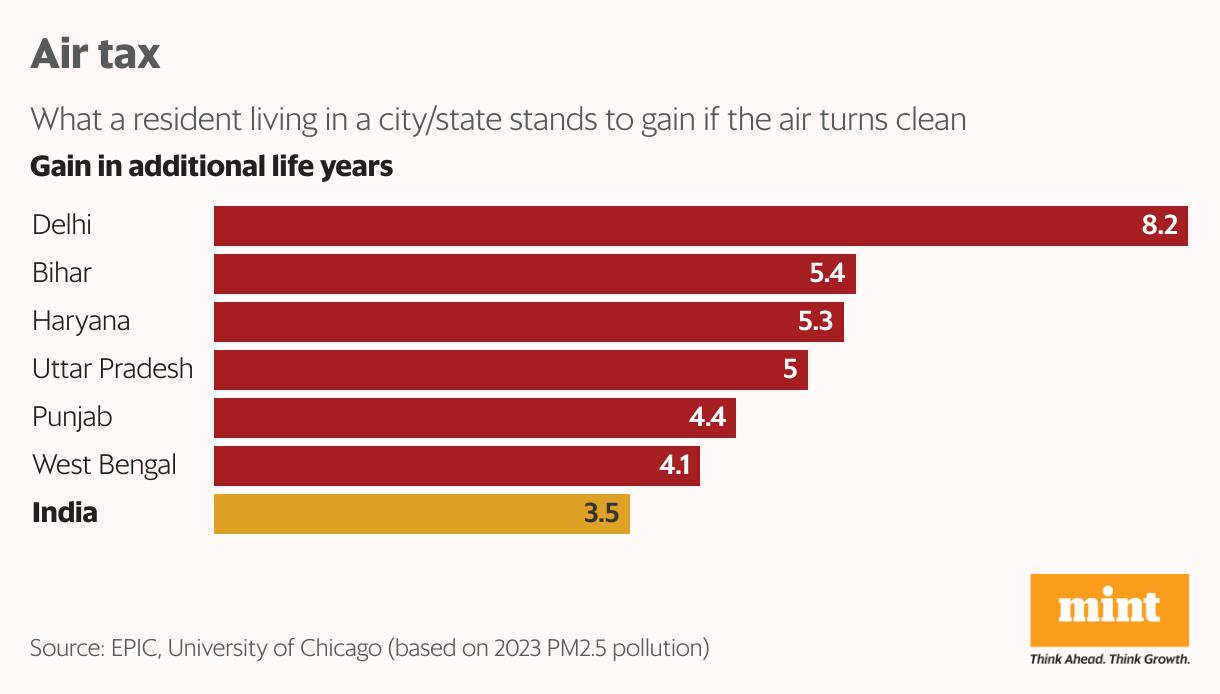

In India, the average life expectancy is 72 years. But deteriorating air quality is now threatening to shorten lives. As per a 2025 report from the Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago (EPIC), an average Indian is losing 3.5 years of their life due to dirty air. And for a resident of its national capital Delhi, the life expectancy is shortened by 8.2 years.

The science here is quite clear. Life spans are shortened by particulate matter pollution, particularly PM2.5, which are fine particles of 2.5 microns or less in diameter. PM2.5 particles can penetrate deep into the respiratory system, enter the bloodstream, and increase the risk of cardiovascular and neurological diseases, cancer and premature death. Children are more vulnerable to air pollution because they breathe more air per unit of body weight. Due to a higher respiratory rate compared to adults, children inhale larger doses of pollution when exposed to the same environment.

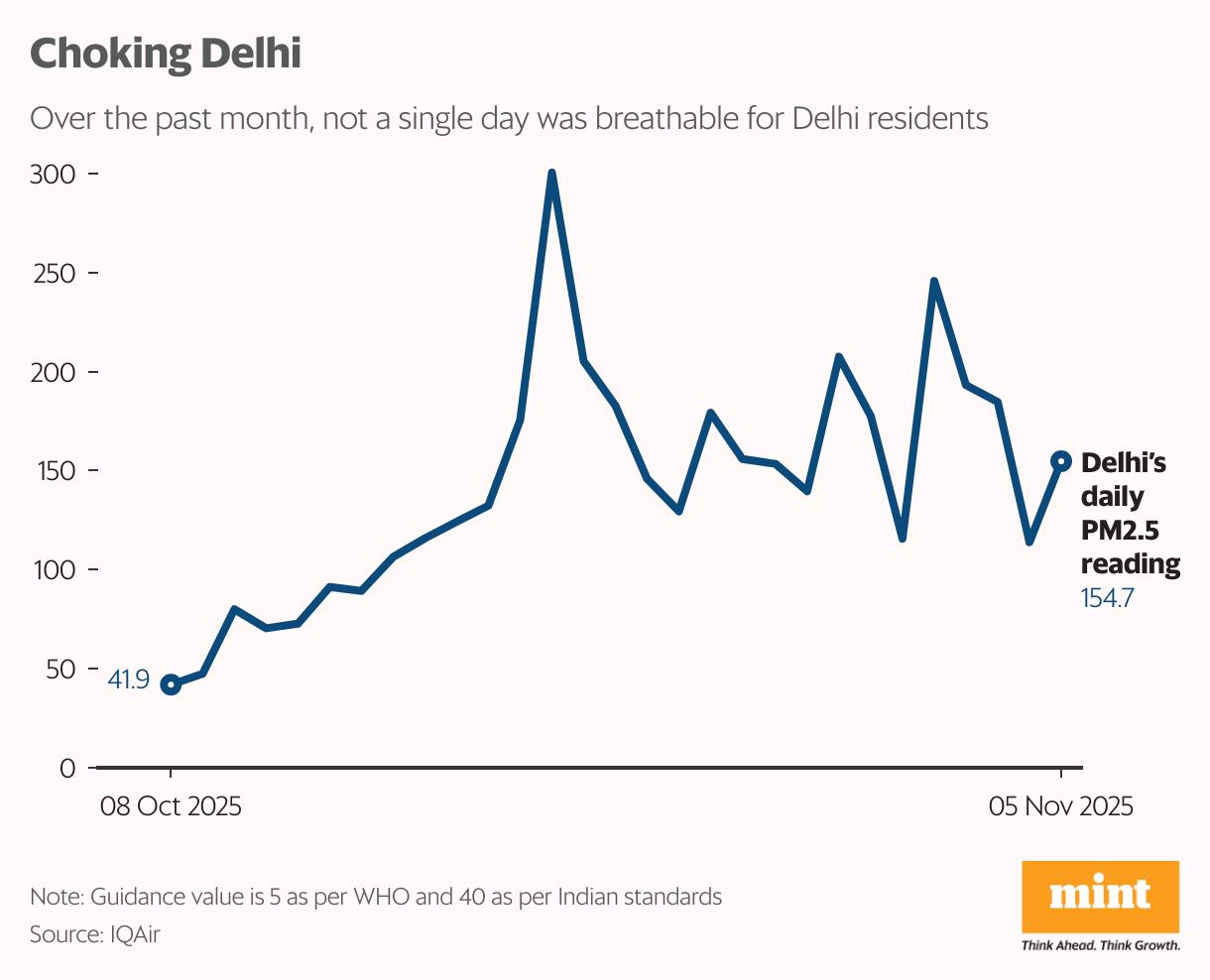

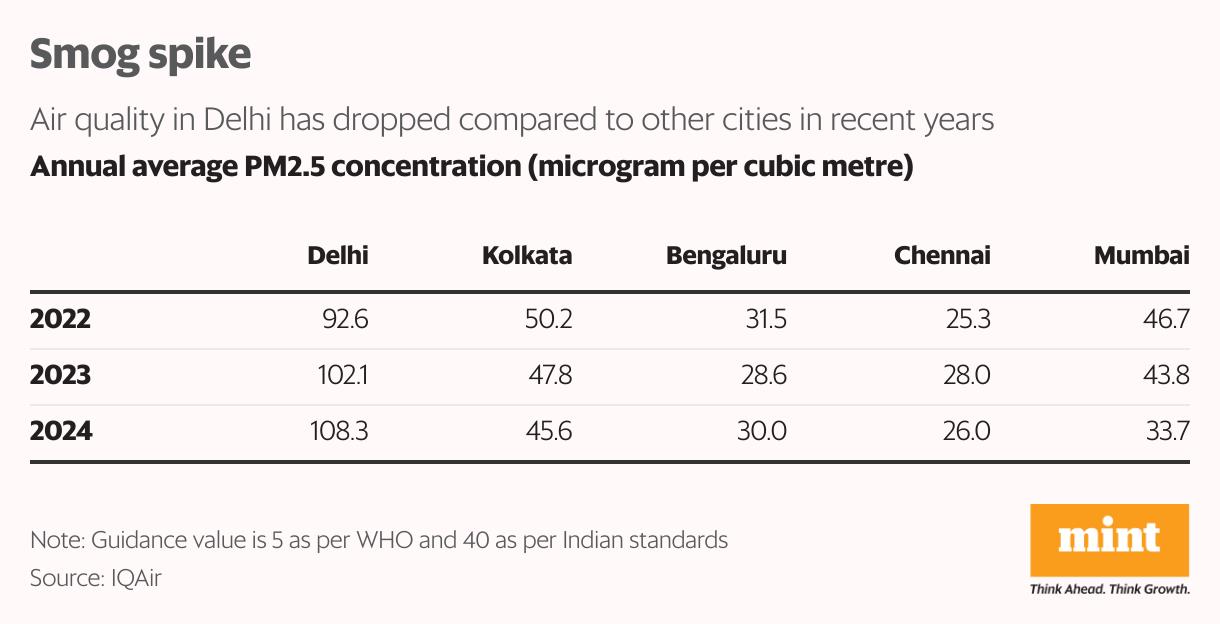

In 2024, the average PM2.5 concentration in India was 50.6 microgram per cubic metre. This is 10 times the World Health Organization's (WHO) guideline value, and higher than India's own annual PM2.5 standard of 40 micrograms per cubic metre. In 2024, the average PM2.5 reading of Delhi was 108.3: over 20 times the desired value, as per the IQAir 2024 World Air Quality Report.

In 2016, India launched its own air quality index (AQI) and a year later set up the National Clean Air Programme. But none of this has solved the dirty air problem, particularly in North India. Data from the University of Chicago shows that for the entire country, air pollution levels have gone up by 63% since 1998. Had pollution levels stayed at 1998 levels, the average Indian would have gained 1.5 years, not lose 3.5 years of their lives as today.

How has 2025 fared so far for the Delhi National Capital Region (NCR), which is home to more than 21 million residents? As per the environment ministry, the average AQI for Delhi-NCR between January and October was 170, the lowest since 2018 (except for 2020 when a national lockdown due to the covid-19 pandemic led to a sharp improvement in air quality). But this period of relatively cleaner air in 2025, due to ample rains washing away pollutants, went up in flames literally, beginning Diwali. After the Supreme Court allowed the bursting of so-called 'green' crackers, Delhi woke up the day after Diwali to a thick layer of smog. Data from the Central Pollution Control Board showed an average AQI of 359. The air quality was 'very poor' and the worst of the past three years.

Pollution levels are set to worsen in the coming days and months, as the winter sets in. Let's take a close look at the factors driving air pollution, the possible solutions and if Delhi-NCR can ever clean up its air.

What are the primary factors?

North India's pollution is the result of multiple factors, some which are round-the-year phenomena while others are winter-specific. Round-the-year sources are vehicular emissions, industries in the neighbourhood, construction dust and biomass burning for cooking. In winter, burning of paddy stubble by farmers in Punjab and Haryana, and biomass burning for heating add to the pollution load.

During winter, a thermal inversion intensifies the pollution. Since the air close to the soil surface is dense and cold, the warm air above blocks the cooler air, trapping it by forming an atmospheric lid. Due to low wind speed, pollutants are not dispersed in the wider area, turning the national capital into a gas chamber. A valley effect also takes place as Delhi is surrounded by hills and mountains like the Himalayas and the Aravallis, which trap polluted air in the valley. So, the air quality in Delhi-NCR is determined by sources of pollution, meteorological conditions and its geography.

Do we know which sources contribute how much?The last pollution apportionment (or sources of pollution) study for Delhi NCR was carried out back in 2018 by the Automotive Research Association of India and The Energy and Resources Institute, a Delhi-based environment think tank. It showed that vehicles contributed between 18-23% to Delhi's PM2.5 pollution through the year. From summer to winter, the share of dust and construction gradually reduces from 34% to 15%, while the share of biomass burning increases from 15% to 22%. The contribution of industry sources range between 11% and 13%. Interestingly, the study also found that Delhi's own sources contribute just about 36% of the pollution load in winter and 26% in the summer. This simply means that to clean up Delhi's air, a collaboration with neighbouring states like Haryana, Punjab, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh would be needed.

On a more regular basis, the Decision Support System for Air Quality Management in Delhi releases daily estimates of pollution sources. For instance, on 1 November, the transport sector contributed nearly 18% to the PM2.5 load while stubble burning contributed 9%. This data again shows that Delhi's own sources contribute less than a third of the air pollution load. A grey area in this data is 'other sources' which are often seen to contribute over 30% to Delhi's pollution load.

View Full Image

On 1 November, the transport sector contributed nearly 18% to the PM2.5 load while stubble burning contributed 9%.

“This 'other' category does not lead to easily identifiable responsibility for authorities because there is nothing called other in the governance system... but since we know the broad range as to which sources contribute to how much pollution, the focus should be on reducing emissions from specific sources going beyond tracking only air quality," said Abhishek Kar, fellow at the Delhi-based Council on Energy, Environment and Water.

Reducing emissions from specific sources-say, waste or stubble burning-may not show up immediately in air quality since AQI is heavily influenced by factors like wind speed and temperatures.“So, the success of reducing air pollution will critically depend on day-to-day boring governance on how well we are able to enforce action to reduce emissions," Kar said.

Are there less spoken of factors that worsen air quality?The State of Global Air Quality 2025 report, released in October, estimated that air pollution led to more than 2 million deaths in India in 2023. The report also noted that if all households using liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) as a cooking fuel in India exclusively use LPG (and not solid fuels like wood, cow dung or coal), India could avert 150,000 deaths annually. This is because solid cooking fuels contribute nearly 30% to ambient household-level air pollution.

Another PM2.5 inventory analysis by the Noida-based think tank International Forum for Environment, Sustainability and Technology (iForest) shows that residential cooking and heating contributes over half to Delhi-NCR's PM2.5 load. A 75% subsidy on LPG cylinders for low-income families, estimated to cost around ₹7,000 crore annually, can clean up Delhi's air and reduce premature deaths due to air pollution.

Household level PM2.5 is a significant contributor to mortality in most states in India, said a 2023 study published in the journal Environmental Science & Technology. It found that India could avoid 716,381 deaths by eliminating residential combustion or use of solid fuels for cooking and heating.

So what measures are being taken to lower emissions?The Commission for Air Quality Management (CAQM) steps in with short-term measures as air pollution levels worsen. These include curbs on entry of polluting vehicles and restrictions on construction and demolition activities. This year, Delhi also tried a few cloud seeding experiments but these failed to induce rains due to low moisture in clouds. Additionally, the city uses anti-smog guns that spray a fine mist of water to lower pollution levels at specific locations. Meanwhile, the Supreme Court, after being informed that only 9 out of 37 air quality monitoring stations functioned on Diwali, has sought a detailed report from CAQM and the Central Pollution Control Board.

View Full Image

An anti-smog gun in New Delhi, on 4 November. (PTI)

Back in 2001, the city made it mandatory to use CNG as a fuel for public transport instead of diesel. Later, emission norms were set for coal-based power plants in Delhi's vicinity. The city also introduced a policy to phase out old and polluting vehicles. Instances of farm fires, which cause a temporary spike in winter pollution, have been on a decline as farmers adopted practices like gathering the paddy stubble with hired machines and supplying it to biofuel manufacturers. However, scientists at Nasa's Goddard Space Flight Center have cautioned that farmers may be evading scrutiny-they set fire to fields after monitoring satellites have passed through the region.

So, what remains to be done to clean the air in Delhi-NCR?The most important statistic in the debate around air pollution is the fact that only around 30-35% of Delhi's pollution comes from its own sources. So, experts suggest adopting an airshed approach-because it is a regional problem. This means coordinating with neighbouring states to devise an emission reduction plan. Since the last emission inventory analysis was done back in 2018, it's time for state governments to come together for an updated study on sources of air pollution and their respective shares.

“The Indo-Gangetic plain is hugely disadvantaged due to its geography and insufficient natural ventilation, especially during the winter... So a regional approach is absolutely critical. The solutions (from promoting cleaner cooking fuels and waste disposal to electric vehicles and reducing industrial emissions) have to be implemented not just for Delhi but across the region with equal intensity, scale and speed," said Anumita Roychowdhury, executive director at the Delhi-based Centre for Science and Environment.

What is required is an inter-state council to create state level action plans and fix responsibility, Rowchowdhury added. But Delhi, including its residents, tend to discuss the scourge of air pollution only during the winter months. Unless air pollution becomes a major public campaign, it seems unlikely that governments will act.

Is there a global success story?

There are several. One prominent example is Accra, the capital of Ghana, home to 5.5 million people. The city implemented multiple innovative programmes to reduce pollution from sources like transport, cooking fuel and open burning of waste. It did so with a strong focus on communicating health benefits, aiding families to switch to cleaner fuels and by communicating progress to citizens via regular press conferences.

Another city comparable to Delhi's size that successfully cleaned up its air is Beijing in China. Between 2013 and 2022, the city's average PM2.5 concentration declined by 67% leading to cleaner air for 22 million residents. The city scaled up financial investments (a sixfold increase between 2013 and 2017), shut down or moved high-pollution enterprises and switched to cleaner household fuels and electric vehicles. The authorities also adopted a regional approach spanning Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei. In 2024, Beijing's average PM2.5 concentration was 31 microgram per cubic metre, less than a third of Delhi's (108).

Writing for the World Economic Forum in 2020, Delhi-based chest surgeon Arvind Kumar observed that he rarely sees normal pink lungs. In the 1980s, over 90% of the lung cancer patients were smokers. But not any more: about half the lung cancer patients were non-smokers, found a 2018 study by a Delhi hospital.

Back in 2018, an installation depicting a pair of human lungs fitted with HEPA filters and fans to mimic breathing was set up outside a Delhi hospital. By the tenth day, the lungs had turned completely black. Over the years, the evidence has mounted with numerous studies pointing that air pollution is a leading cause of multiple diseases, including death. But despite years of discussions and seasonal outrage, Delhi has been unable to fix its dirty air. For the residents, is leaving the city, call it Dexit, the only option left?

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment