The Price Of Pragmatism: What India Gains (And Loses) By Courting The Taliban

By Girish Linganna

In a move that would have seemed unthinkable just a few years ago, Taliban Foreign Minister Amir Khan Muttaqi arrived in New Delhi on October 9 for an eight-day official visit that marks a watershed moment in India's foreign policy. His meetings with External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar, followed by visits to Islamic seminaries in Agra and Deoband, represent India's most significant engagement yet with the Taliban regime. New Delhi has agreed to set up full fledged embassy in Kabul, this is a major turn in India-Taliban relations., This visit signals a pragmatic recalibration driven by shifting regional dynamics and India's own security imperatives. Yet this approach comes with thorny questions about how India reconciles engagement with a regime notorious for its oppressive treatment of women and regressive policies.

Understanding who Amir Khan Muttaqi is helps explain the complex web India now navigates. Born in 1970 in Helmand province, Muttaqi's life story mirrors that of many Taliban leaders who came of age during Afghanistan's decades of conflict. At just nine years old, he fled to Pakistan following the Soviet invasion, receiving his education in refugee schools while joining the fight against the communist government. When the Taliban movement emerged in 1994 and swiftly captured Kandahar from feuding warlords, Muttaqi joined their ranks, quickly rising to become Director General of the city's radio station and a member of the Taliban's High Council. By March 2000, he held the position of Education Minister, a role he kept until American forces arrived. His involvement in the 2019 negotiations with the United States and his subsequent appointment as acting Foreign Minister after the Taliban's 2021 return to power demonstrate his enduring influence within the movement.

India's history with the Taliban has been fraught from the start. The 1999 hijacking of Indian Airlines flight IC-814 to Kandahar forced then-External Affairs Minister Jaswant Singh into difficult negotiations with Taliban Foreign Minister Wakil Ahmed Muttawakil. A telling encounter from 2000, documented in Avinash Paliwal's book on India's Afghanistan policy, illustrates the challenges India faced. When Taliban representative Mullah Abdul Saleem Zaeef met India's ambassador to Pakistan, Vijay K. Nambiar, in Islamabad, the friendly atmosphere yielded nothing substantive. Nambiar concluded that genuine understanding between India and the Taliban remained impossible, with Pakistan's influence over the movement creating an insurmountable barrier to meaningful engagement.

See also India's Opposition To Trump Bid To Take Over Bagram Airbase Has Special SignificanceSince the Taliban's return to Kabul in August 2021, India has pursued what officials describe as cautious engagement. Just hours after the last American troops departed, Indian ambassador to Qatar Deepak Mittal met with Sher Mohammad Abbas Stanekzai, head of the Taliban's political office in Doha. Stanekzai, interestingly, had trained at the Indian Military Academy in Dehradun during the 1980s as part of a bilateral defence programme. This meeting, held at the Taliban's request, came after Stanekzai publicly emphasized India's regional importance and expressed desire to maintain Afghanistan's cultural, economic, political, and trade ties with India.

Despite these diplomatic overtures, India has not hesitated to voice concerns about the Taliban's governance. When the Taliban announced a cabinet devoid of women and minority representation, India called for an inclusive government. In September 2021, India officially recognized the Taliban as those holding power across Afghanistan, a carefully worded acknowledgment that fell short of formal recognition. India's strategy has centered on distinguishing between the Taliban regime and the Afghan people, focusing humanitarian efforts on ordinary Afghans while maintaining limited official contact with their rulers. This approach manifested in December 2021 when India sent essential medicines to Afghanistan, followed by the deployment of a technical team to Kabul in June 2022 to oversee humanitarian projects and maintain embassy operations.

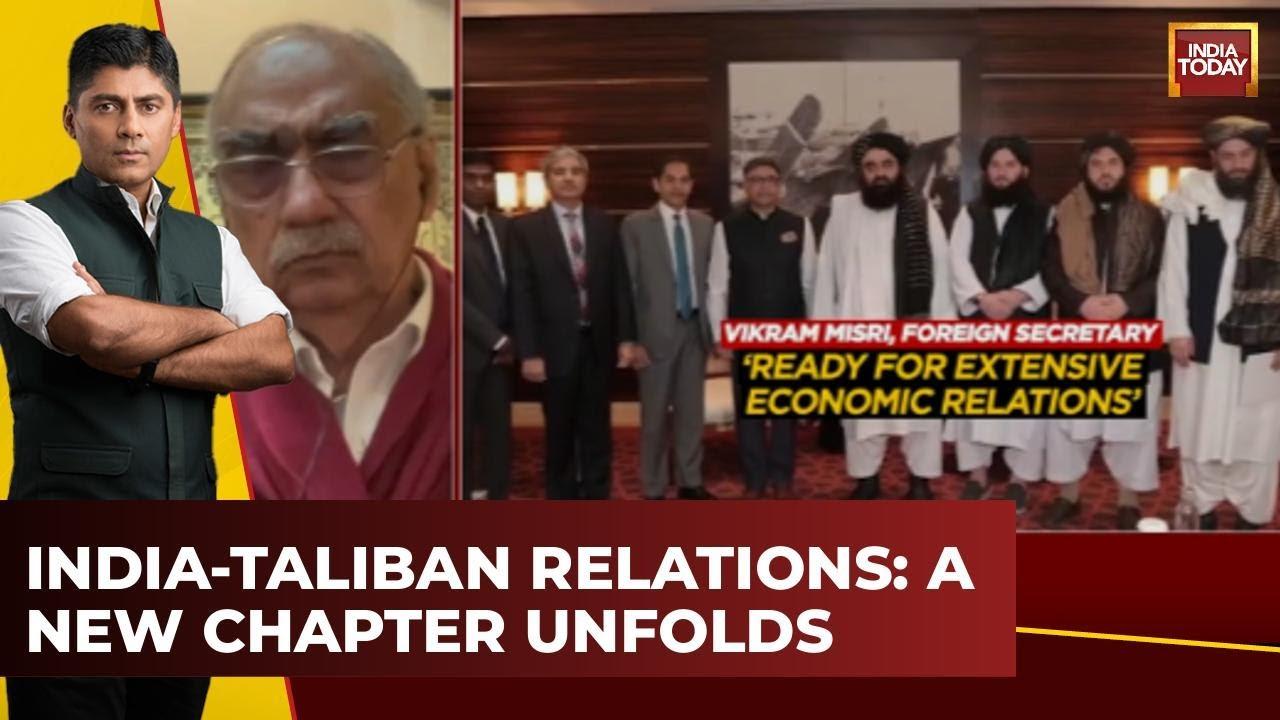

The relationship has progressed through fits and starts. India expressed concern when the Taliban banned women from universities in December 2022. The Afghan embassy in India announced its closure in late 2023, citing lack of support from the Indian government. Yet engagement continued with Foreign Secretary Vikram Misri meeting Muttaqi in Dubai in January 2025, and External Affairs Minister Jaishankar speaking with him by phone in May 2025 after India and Pakistan agreed to halt military strikes following the Pahalgam terror attack.

The question naturally arises: why engage now, and why so publicly? The answer lies in a dramatically altered regional landscape. Pakistan, once the Taliban's primary backer, has become an adversary. Iran faces its own challenges and diminished influence. Russia remains preoccupied with its war in Ukraine. The United States under Donald Trump's second term has adopted a different approach to Afghanistan. Most significantly, China has moved to establish formal diplomatic relations with the Taliban, exchanging ambassadors and positioning itself as a major player in Afghanistan's future. India recognizes that stepping back now risks surrendering years of investment and influence in a country critical to its security interests.

See also Youth-led outrage turns deadly across NepalIndia's support has been substantial and visible. The country has sent fifty thousand metric tonnes of wheat, hundreds of tonnes of medicines and earthquake relief supplies, pesticides, over one hundred million polio vaccine doses, Covid vaccines, and hygiene kits for drug rehabilitation programmes. Both countries have discussed sports cooperation, particularly in cricket, which enjoys immense popularity among Afghan youth. They have also agreed to utilize Iran's Chabahar port to facilitate trade and deliver humanitarian aid, while India has committed to continuing development projects across all thirty-four Afghan provinces.

The Taliban, for its part, has requested that India issue visas to Afghan traders, patients, and students. This presents challenges given India's lack of formal recognition, security concerns about travellers from Afghanistan, and the absence of functioning visa operations at its Kabul embassy. Yet the very fact that such practical matters are being discussed reveals how far this relationship has evolved from the hostility of earlier decades.

India now walks a tightrope between pragmatic engagement and principled opposition to the Taliban's treatment of women and minorities. The global context has forced Delhi's hand, but the path ahead remains treacherous. Each meeting, each humanitarian shipment, each cricket match discussed must be weighed against the regime's continued oppression. Whether India can maintain this delicate balance, pursuing its strategic interests while not abandoning its values, will define not just its relationship with Afghanistan but its broader role in a rapidly changing region. (IPA Service )

The article The Price Of Pragmatism: What India Gains (And Loses) By Courting The Taliban appeared first on Latest India news, analysis and reports on Newspack by India Press Agency) .

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Most popular stories

Market Research

- Pepeto Highlights $6.8M Presale Amid Ethereum's Price Moves And Opportunities

- Codego Launches Whitelabel Devices Bringing Tokens Into Daily Life

- Zeni.Ai Launches First AI-Powered Rewards Business Debit Card

- LYS Labs Moves Beyond Data And Aims To Become The Operating System For Automated Global Finance

- Whale.Io Launches Battlepass Season 3, Featuring $77,000 In Crypto Casino Rewards

- Ceffu Secures Full VASP Operating License From Dubai's VARA

Comments

No comment