Robert Munsch Has Prepared For The Eventual End Of His Story, But His Letters And Books Keep Speaking

One author who wrote me back was the beloved Canadian children's author Robert Munsch. His stories, including Mortimer, Thomas' Snowsuit and Love You Forever, have sold more than 87 million copies, been translated into dozens of languages and are staples in classrooms, homes and libraries worldwide.

In mid-September, a Munsch profile appeared in the New York Times outlining how dementia has affected the author's life, and his decision to elect medically assisted death (MAiD) when the time comes.

While Munsch's daughter has said he is“NOT DYING!!!” and doing well, the recent coverage has reignited national conversations about dignity, decline and ethical questions raised by MAiD.

Munsch's letter-writing opens journalist Katie Engelhart's New York Times Magazine piece. She notes that when Munsch received many letters from a class, he'd reply with a single letter, often with an unpublished story that included real names of some students. But when children wrote on their own, Munsch always responded.

According to Scholastic, one of his publishers, Munsch receives about 10,000 letters a year.

How stories shape who we becomeI've carried Munsch's letter, and other author letters, with me for almost three decades. They now live in a shoebox on my office window sill - a reminder that the child who wrote them still lingers nearby.

I see now that in writing to the authors I admired, I was beginning to understand how stories can shape a sense of self - how young people make sense of their identities through reading.

In my research, I've examined how reading is a powerful tool for exploring and building identity, belonging and community. I've engaged with youth across urban and rural settings and those living on reserve. I've always found young people to be the most reliable, compelling narrators of their own stories.

Too often, both scholars and popular narratives get caught in unhelpful binaries - adult versus child, innocent versus knowing - that flatten the richness of children's lives, positioning them as somehow incomplete. I'm more interested in what happens when we think of adults and children as akin: different, yes, but connected.

All these years later, I'm returning to Munsch's letter, not just as a material remnant of my childhood, but as evidence of what's possible when an author takes their child-reader seriously.

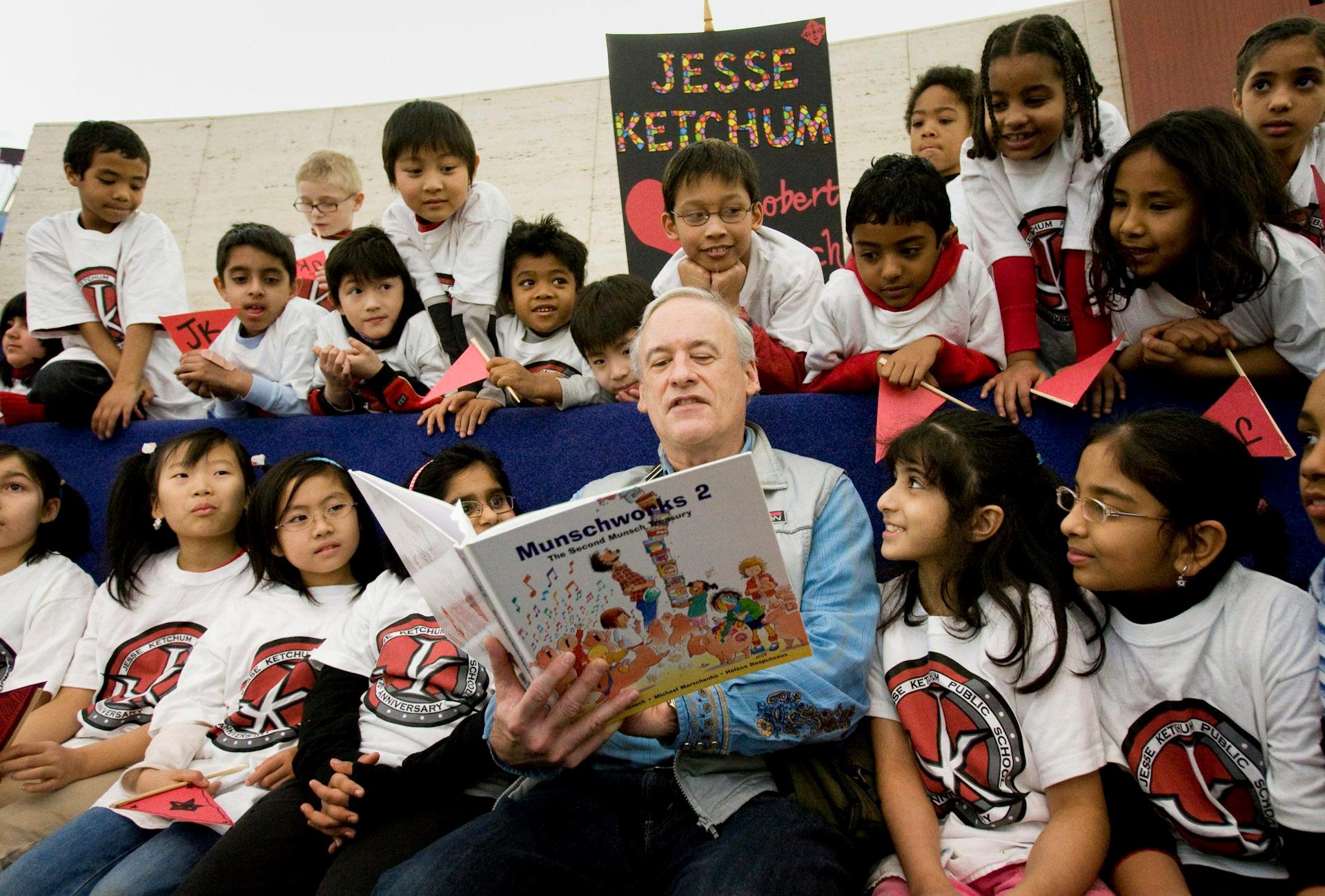

Munsch reads to children from one of his books at City Hall in Toronto in 2009. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Frank Gunn Literacy is a relationship

Literacy is not only a skill but a relationship, nurtured through moments of attention, dialogue and care. And here is where Munsch is masterful. His career has been an extended epistolary experiment in listening and taking children seriously.

“I talk to kids, and I listen to kids,” he explains on his website. Munsch improvised stories in front of children, shifting in response to their laughter or protest. He drew inspiration directly from them.

“My stories have no adult morals. They're not to improve children. They're just for kids to like,” he shared on CBC radio in 2021.

Munsch also writes honestly on his website about his background - how he was“not a resounding academic success.” He writes openly about his mental-health challenges, encouraging parents to have brave conversations with their children.

It's no surprise, then, that Munsch has openly shared his most recent struggle with dementia, prompting readers across the ages to share memories of how his stories have shaped their lives.

Small exchanges matter tremendouslyAt a time when debates about reading for pleasure and children's creativity are making headlines, these small exchanges matter tremendously.

Recent Canadian data suggest both promise and concern. According to Scholastic's Kids and Family Reading Report, 91 per cent of children aged 6 to 17, and 97 per cent of parents, agree that being a reader is essential. Yet the same report shows that children's enjoyment of reading declines sharply with age, and that many struggle to connect with books.

CBC video of Robert Munsch telling the story of 'The Paperbag Princess.'

The National Literacy Alliance has warned that one in five Canadian adults still face serious reading challenges, calling for a national strategy. Data from the United Kingdom's National Literacy Trust reports similar findings.

In response to declining rates in reading for pleasure, the Booker Prize has launched a new award for children's fiction, with young people on its adjudication board.

Hearing children, fullyMunsch understood children as whole people decades ago. Not only is he honest, but he makes it clear that hearing from children matters. He wrote to me:

Briefly, 11-year-old me, a young girl from rural Ontario, was that one person.

“I live in Guelph,” Munsch described to me.“It is surrounded by farms. My house is next to a hill. I have an office in the basement.”

It reads like a letter between friends.

One reader, one writerWhen Engelhart's article appeared, I pulled out my shoebox, noticing that Munsch ends his letter with a question:“Which book is your favourite?”

I had missed it at the time.

His response to my letter project was also a gesture of kinship. Munsch's question placed the power in my hands, inviting child-me back into the conversation. I wish I had taken him up on it.

Long before“reading crises” made headlines, Munsch understood that stories are relational. His 1996 letter to me, written in the same voice that filled classrooms with laughter, embodied that belief.

In responding, he modelled what literacy can look like at its most human scale: one reader, one writer and a story shared between them.

The stories we carryNow, as his voice begins to recede, those exchanges take on new weight.

Munsch's end of life invites reflection for Canadian cultural memory. Munsch, as a Canada Walk of Fame inductee, unveils his star in Toronto in 2009. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Sean Kilpatick

Contemplating Munsch's end of life invites broader reflection for Canadian cultural memory. Children's literature often counts for less in national literary canons, but it carries enormous weight - because generational reading connects us.

What happens when a central figure of that literature fades? How do we preserve not just the texts, but the relational echoes around them?

When Munsch asked me which book was my favourite, he was really asking what story I would carry forward. Three decades later, I'm belatedly responding: it's the letter itself - the conversation, the recognition, the trust.

I carry my shoebox wherever I go. Inside it lives a child's curiosity, the kindness of authors and the reminder that the relations we nurture through stories shape identity in quiet, enduring ways.

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment