How Does A Flaming Piece Of Space Junk End Up On Earth? A Space Archaeologist Explains

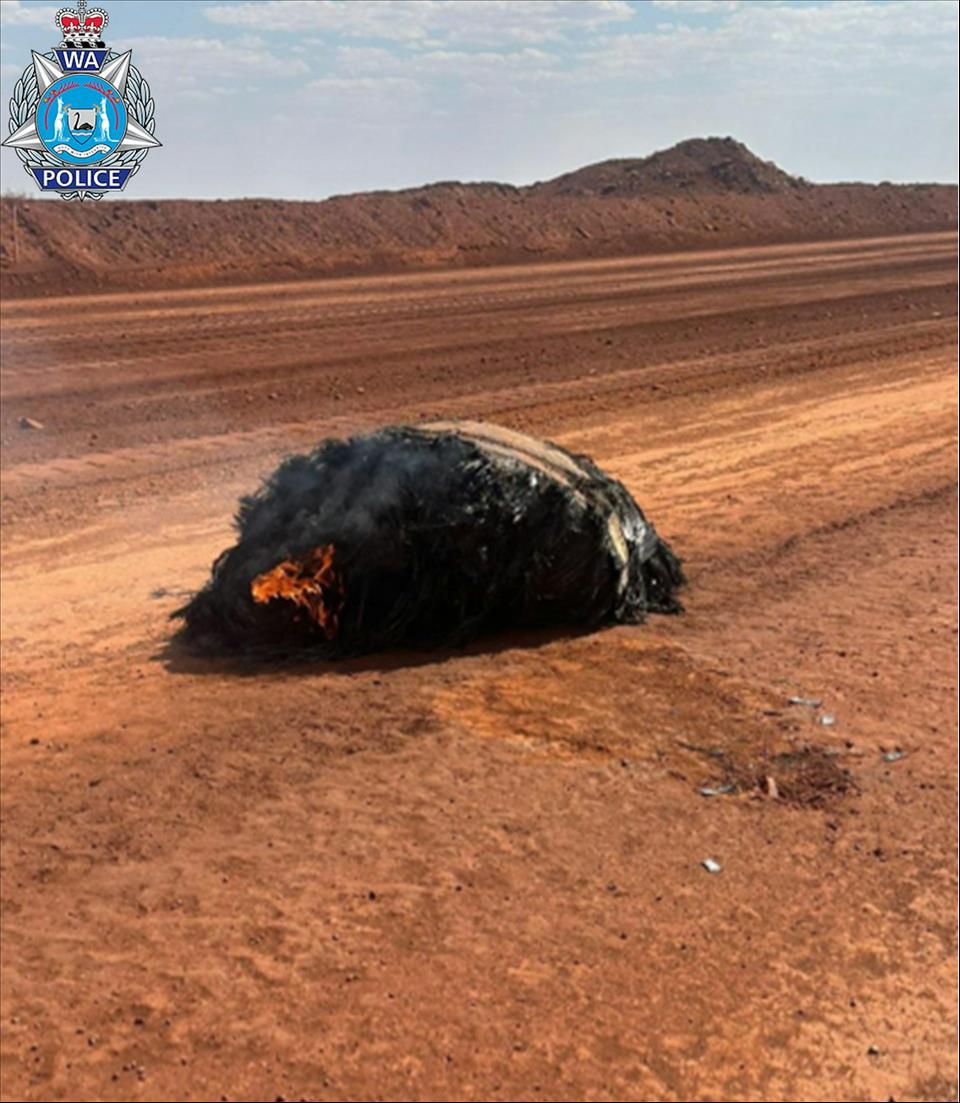

Shortly after the enigmatic item was found on October 18, Western Australia police announced that initial assessments indicated it was made of carbon fibre and“consistent with previously identified space debris”.

The object appears to have come from a Chinese Jielong-3 rocket – possibly the one launched in September which deployed 12 satellites in low Earth orbit.

The object's suspected identity was corroborated by expert debris watchers, who noted the orbital path of the rocket's fourth stage passed over Western Australia at a time consistent with the debris' discovery.

The Australian Space Agency told The Conversation the debris is“likely a propellant tank or pressure vessel from a space launch vehicle” and that it will conduct further technical analysis to confirm its origin.

Regardless, the object's fall to Earth highlights the growing problem of space junk – and how humanity is dealing with it.

Crash landing from spaceThe area surrounding Earth is becoming increasingly crowded. It's home to more than 10,000 active satellites, and possibly up to 40,000 pieces of space junk bigger than 10 centimetres. By the end of this decade, roughly 70,000 satellites could be in low Earth orbit, at altitudes below 2,000 kilometres.

Space junk refers to any piece of human-made material in space that doesn't have a purpose. This includes dead satellites and rocket stages discarded after they've delivered satellites to orbit.

Space junk disposal generally relies on the debris being pulled back into the atmosphere and burning up through friction and heat.

The most problematic class of space debris is spent rocket stages. A paper presented at the International Astronautical Congress in Sydney earlier this month listed the 50 most concerning pieces of space junk in low Earth orbit – 88% of which are rocket bodies.

However, space junk is being created at a higher rate than it is re-entering Earth's atmosphere. And now we know burning metals create harmful particulates of alumina and soot, which impact the ozone layer we rely on to filter out ultraviolet radiation.

Sometimes fuel tanks and pressure vessels reach the ground mostly intact instead of being completely incinerated. The metal alloys used to make them have a higher melting point than other spacecraft material, and they are often insulated with carbon fibre strips.

Space agencies, defence organisations and amateur debris watchers are constantly tracking the orbit – and re-entry – of space junk. This is a complex task – in part because these objects are hurtling around Earth at speeds of up to 28,000 kilometres per hour.

Controlled versus uncontrolled re-entriesThe atmospheric re-entry of most space junk is uncontrolled.

Once the spacecraft runs out of fuel or batteries to power its thrusters, its orbit starts to drift. If the debris is large enough, like an old satellite or rocket body, where and when it re-enters can usually be predicted. Most of the time this is over the sea or in areas with low populations – just because this is most of the planet.

But not always. For example, in April 2022, parts of a Chinese third stage rocket crashed to Earth near a house in the Indian village of Ladori in the Maharashtra region, startling the residents who were preparing a meal at the time.

One strategy to reduce space junk is known as passivation. Passivation involves depleting all fuel and batteries so the spacecraft doesn't spontaneously explode, creating more debris. This leaves no fuel or communications for a controlled re-entry.

A controlled re-entry involves guiding the spacecraft to a location with a low risk of harm to people, property or the environment.

One such region is the so-called“space cemetery” – a point in the Pacific Ocean roughly 2,700 kilometres from any landmass. There are about 300 spacecraft on the sea bed there, and this is where the International Space Station will be brought down at the end of the decade.

Finding the ownerThe first stage of the investigation into the suspected space debris found in Western Australia will be determining who owns it.

The 1967 Outer Space Treaty says the state that authorised a rocket or satellite launch is liable for any damage it causes on Earth – even if a private company actually conducted the launch.

If the object does turn out to be from a Chinese rocket, the next step will be contacting China about its return or disposal. They may choose to leave it with Australia, as India did with a rocket fuel tank which washed up on a beach in Western Australia in 2023.

It appears the rocket body didn't cause any harm so the negotiations won't involve liability or insurance claims. The debris landed in a landscape already heavily impacted by mining activities so it is unlikely a claim for environmental harm can be made.

Better end-of-life planning is neededEnd-of-life planning is critical for future space debris management in low Earth orbit, as there is currently no capacity to actively remove debris from that region.

The standard used to be that no spacecraft should remain in orbit after 25 years beyond the end of its mission life. Now, the expected standard for low Earth orbit is five years.

Technologies are being developed to service and refuel satellites on orbit to extend the time they can remain active in space. New materials, such as wood, are being trialled to reduce pollution of the upper atmosphere.

The European Space Agency is promoting the Zero Debris Charter which invites signatories to commit to becoming debris-neutral – that is, creating no new debris with each mission – by 2030.

In the short term, we can expect to see an increase in the amount of debris crashing down to Earth. But there is hope international collaboration and new technologies will lead to more sustainable use of space, ensuring future generations have equal access to it.

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Most popular stories

Market Research

- Thinkmarkets Adds Synthetic Indices To Its Product Offering

- Ethereum Startup Agoralend Opens Fresh Fundraise After Oversubscribed $300,000 Round.

- KOR Closes Series B Funding To Accelerate Global Growth

- Wise Wolves Corporation Launches Unified Brand To Power The Next Era Of Cross-Border Finance

- Lombard And Story Partner To Revolutionize Creator Economy Via Bitcoin-Backed Infrastructure

- FBS AI Assistant Helps Traders Skip Market Noise And Focus On Strategy

Comments

No comment