William Barak's Missing Art: Wurundjeri Elders Lead The Search To Reclaim Lost Cultural Treasures

William Barak, photographed by Carl Walter.

Walking between two worlds was a necessity for many Aboriginal men of Barak's generation. Alongside his cousin Simon Wonga, he was influential in the early land rights struggles in the southeast of the continent.

Currently, three of Barak's drawings are on display at the University of Melbourne's Ian Potter Museum of Art, as part of the exhibition 65,000 Years: A Short History of Australian Art . They are presented alongside the work of his contemporaries, as well as various contemporary First Nations artists.

Barak is among a small group of Aboriginal artists from the 19th century whose names and artworks are traceable. But while 52 of his works are accounted for, potentially many more remain unaccounted for.

To address this, Wurundjeri Woi-wurrung Elders are working with researchers to locate artworks by Barak that have disappeared from public view and the historical record.

Artworks coming homeBarak lived from 1824 to 1903. He belonged to the Wurundjeri-willum family group, and became a leader later in life.

The Barak apartment building in Carlton, Melbourne, has a facade which, when viewed from a distance, portrays Aboriginal artist and activist William Barak. , CC BY-SA

He made drawings and carved weapons and tools at Coranderrk Aboriginal Station, near Healesville, which became a popular tourist destination during his lifetime. Some visitors became custodians of Barak's work, and would donate these works to galleries, museums and historical societies years later.

In 2022 two artworks , a drawing and a shield, were bought at an auction by the Wurundjeri Woi-wurrung Cultural Heritage Aboriginal Corporation, with support from the public and the state Labor government. Both works had been made by Barak at Coranderrk in 1897, and gifted to his neighbour Jules de Pury.

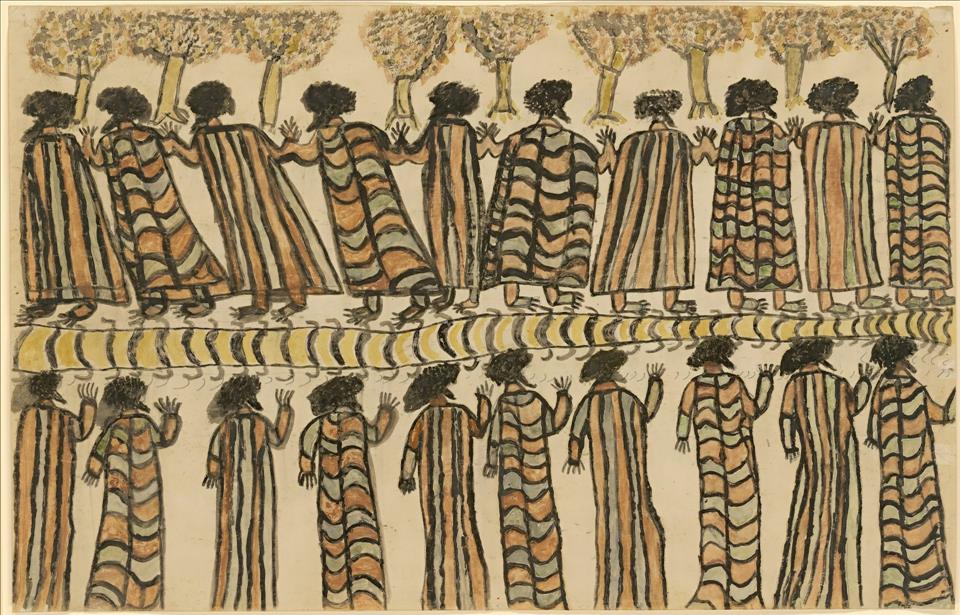

Jules de Pury's descendants, who live in Switzerland, chose to sell the works rather than return them to Barak's descendants. The drawing, Corroboree (Women in Possum skin cloaks), sold for more than A$500,000, and the parrying shield, featuring rarely seen designs, sold for more than $74,000 (far exceeding its estimated sale price of around to $20,000).

This wasn't the first time a drawing by Barak was auctioned, and crowd-funding was used to try and bring the works back to Country. In 2016, a drawing depicting a ceremony was acquired for more than half a million dollars by a private collector, only to disappear from view.

In hopes of avoiding a repeat of this scenario, and after the successful return of two works in 2022, the Wurundjeri Woi-wurrung community have launched a project to locate Barak's missing works.

Windows to the pastBarak's drawings depict Kulin life before invasion and contain important cultural knowledge that community need access to.

For example, Corroboree (Women in Possum skin cloaks), tells us about daily life. As Wurundjeri language specialist Mandy Nicholson said at the time of the auction :

William Barak, Corroboree (Women in possum skin cloaks), 1897. Sotheby's

Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung Elder Uncle Colin Hunter described Barak's artworks as“windows into our culture”, noting that Barak intended them to survive:

It is vital community have access to this heritage, which we view as patrimonial (inherited from our ancestors), to continue the revival of culture which has grown from strength to strength in recent decades.

Becoming artBarak's artworks haven't always been understood as art.

Research by one of us (Nikita Vanderbyl) traces settler understandings of Barak's works. How were they understood prior to the 1980s, when there were major re-evaluations that labelled Aboriginal art as“art”? What did settlers see when they looked at Aboriginal cultural productions?

Fleeting moments of understanding, exchange and recognition provide a so far overlooked genealogy of the changing reception of Barak's paintings and drawings within his lifetime, and up to the 1940s.

The earliest example of Barak's drawings being labelled“Aboriginal art” was possibly in 1897. A newspaper documented the colony's governor, Lord Thomas Brassey, visiting Coranderrk and receiving a bark painting which depicted a ceremony in red and yellow. Although the governor promised to add the gift to his art collection, its location today is unknown.

Links in the colonial art worldA number of impressionists were painting and drawing Wurundjeri Country at the same time that Barak was drawing and painting ceremonies. He developed relationships with four artists including John Mather, a Scottish-Australian watercolourist and etcher.

Mather painted Barak's portrait in 1894 and acquired two of his drawings (now in the State Library of Victoria's collection). Both of these were included in a 1943 exhibition called Primitive Art.

It marked the first time Barak's work was included in an exhibition. It was also the first time cultural productions from Australia's southeast were presented alongside international examples of Indigenous art from Oceania, North America, western Iran and Africa.

The first inclusion of Barak's work in an exhibit was in the 1943 'Primitive Art' exhibition. Untitled (Aboriginal ceremony, with wallaby and emu) was one of the works displayed. State Library Victoria Reconnecting with lost works

Wurundjeri Woi-wurrung community members are now looking to hear from private collectors who are willing to share high-resolution images of Barak's work. The goal is to locate unknown drawings, shields, boomerangs and other objects Barak created at Coranderrk.

If you have a drawing or cultural object made by Barak in your collection, or know about the location of one, please reach out to the authors.

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment