After Treaty Suspension, Kashmir Questions Its Share Of Water

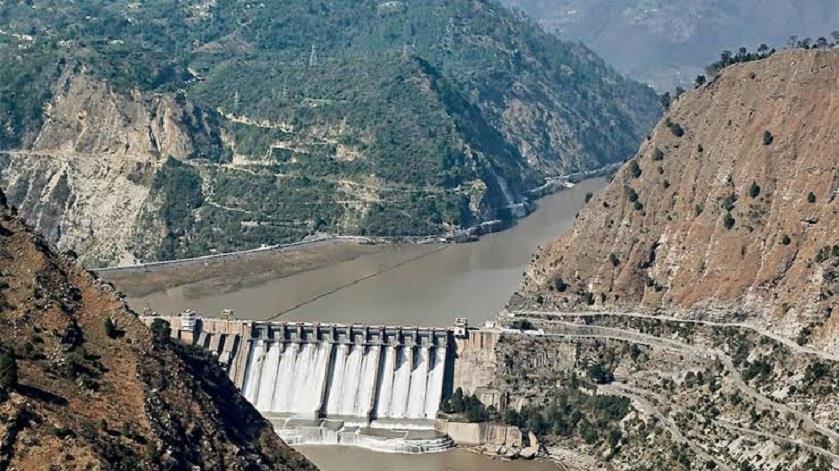

File photo

By Mumtaz Khan

It took a horrific tragedy - the attack in Pahalgam that killed 26 people - for Delhi to suspend the Indus Waters Treaty, one of the world's most celebrated but deeply unequal water-sharing agreements. In the rush of diplomatic expulsions and border shutdowns, one voice stood out.

Jammu and Kashmir Chief Minister Omar Abdullah, speaking bluntly, said,“Let's be honest, we have never been in favour of the Indus Water Treaty. It has been the most unfair document to our people.”

The treaty, signed in 1960 between Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and Pakistan's Ayub Khan, with the World Bank as broker, divided rivers like lines on a map. Kashmir wasn't even consulted.

The Indus, Jhelum, and Chenab - rivers that nourish Kashmir's valleys and mountains - were assigned largely to Pakistan. India got the three eastern rivers - Beas, Ravi, Sutlej - and a limited right to use the western ones for“non-consumptive” purposes like small hydropower and navigation.

Read Also Centre Plans Study To Look Into Max Use Of Pak's Share Of Water Under Now-Suspended Indus Treaty 'Not a Single Drop to Pakistan'In effect, Kashmiris watched as their rivers were turned into bargaining chips in a deal between two distant capitals. India could not build large dams. Storage was severely restricted. Every project faced endless scrutiny, often from international bodies.

The numbers tell their own story. About 80% of the Indus system's flow comes from the three western rivers. Yet Pakistan was granted 70% of the water under the treaty, while India - including Kashmir - was left with just 30%.

This wasn't just about water. It was about power, economy, and future. Kashmir, rich in hydropower potential, remained energy-poor. The state became a land where rivers roared through gorges but villages lived with blackouts. Where floods drowned crops, and farmers were helpless because flood control infrastructure was restricted by treaty rules.

Even small projects like the Kishanganga Hydroelectric Plant became battlegrounds. Years of legal wrangling, arbitration at The Hague, Pakistani objections, while Kashmir waited.

Omar Abdullah's remarks tap into a grievance older than most living Kashmiris. For them, the Indus Water Treaty was a pact signed over Kashmiris' heads, written in a language that ignored their dreams. Their rivers were treated as resources to be allocated between the two nations, while they themselves were treated as afterthoughts.

This week, when Delhi suspended the treaty, it framed the move as punishment for Pakistan. In Kashmir, the feeling was different: maybe a chance had opened, but maybe old wounds were simply being ignored once again.

The question now is simple: will Kashmir finally get a say in how its rivers are used? Or will decisions still be made in Delhi and Islamabad, with Kashmir left holding the short end of the stick?

The stakes are higher than ever. Climate change has altered river flows. Snow melts earlier. Glaciers shrink. Communities that depend on steady water face growing uncertainty. Kashmir needs dams for drinking water, irrigation, and flood control. It needs smart, sustainable hydropower projects to bring energy to remote areas.

None of this can happen without acknowledging what the old treaty never did, that Kashmiri people are the primary stakeholders of these rivers.

The Indus, Jhelum, and Chenab are not just waterways. They are part of Kashmir's memory. The Jhelum winds through the heart of Srinagar, carrying houseboats and prayers alike. The Chenab powers through Kishtwar's mountains, a raw force of nature. The Indus sustains Ladakh's high-altitude communities, where rivers mean life itself.

Delhi's decision to scrap the treaty is being hailed in some quarters as strategic boldness. It could be that. But if it simply replaces one form of centralization with another, it will solve nothing.

A new framework must be built with Kashmiris at the center, not on the sidelines. The people who live beside these rivers, farm their banks, and pray at their waters should shape their future. Anything less would be a repetition of history, with all its injustice.

Until then, the rivers will keep flowing, indifferent to maps and treaties, waiting for a fairer world to catch up.

-

Writer is a Srinagar-based scholar. Views expressed in this article are author's own and don't necessarily reflect KO's editorial policy.

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment