US Media Mention Asian-Named Scientists Less Often

But when the immigration officers rejected his petition, they noted that his name did not appear anywhere in the news articles. News coverage of a paper he co-authored did not directly demonstrate his major contribution to the work.

As this biologist's close friend, I felt bad for him because I knew how much he had dedicated to the project. He even started the idea, as one of his PhD dissertation chapters. But as a scientist who studies topics related to scientific innovation , I understand the immigration officers' perspective: Research is increasingly done through teamwork , so it's hard to know individual contributions if a news article reports only the study findings.

This anecdote made me and my colleagues Misha Teplitskiy and David Jurgens curious about what affects journalists' decisions regarding which researchers to feature in their news stories.

There's a lot at stake for a scientist whose name is or isn't mentioned in journalistic coverage of their work. News media play a key role in disseminating new scientific findings to the public . The coverage of a particular study brings prestige to its research team and the members' institutions. The depth and quality of coverage then shapes public perception of who is doing good science . In some cases, as my friend's story suggests, individual careers can be affected.

Do scientists' social identities, such as ethnicity or race, play a role in this process?

This question is not straightforward to answer. On the one hand, racial bias may exist, given the profound underrepresentation of minorities in US mainstream media . On the other, science journalism is known for its high standard of objective reporting . We decided to investigate this question in a systematic fashion using large-scale observational data.

US pushes ASML to deny maintenance in China TSMC is chasing a trillion-transistor AI bonanza Chinese, African names received least coverage

My colleagues and I analyzed 223,587 news stories from 2011-2019 from 288 U.S. media outlets reporting on 100,486 scientific papers sourced from Altmetric, a website that monitors online posts about research papers . For each paper, we focused on authors with the highest chance of being mentioned: the first author, last author and other designated corresponding authors. We calculated how often the authors were mentioned in the news articles reporting their research.

We used an algorithm with 78% reported accuracy to infer perceived ethnicity from authors' names . We figured that journalists may rely on such cues in the absence of scientists' self-reported information. We considered authors with Anglo names – like John Brown or Emily Taylor – as the majority group and then compared the average mention rates across nine broad ethnic groups.

Our methodology does not distinguish black from white names because many African Americans have Anglo names, such as Michael Jackson. This design is still meaningful because we intended to focus on perceived identity.

We found that the overall chance of a scientist being credited by name in a news story was 40%. Authors with minority ethnicity names, however, were significantly less likely to be mentioned than authors bearing Anglo names. The disparity was most pronounced for authors with East Asian and African names; they were on average mentioned or quoted about 15% less in US science media than those with Anglo names.

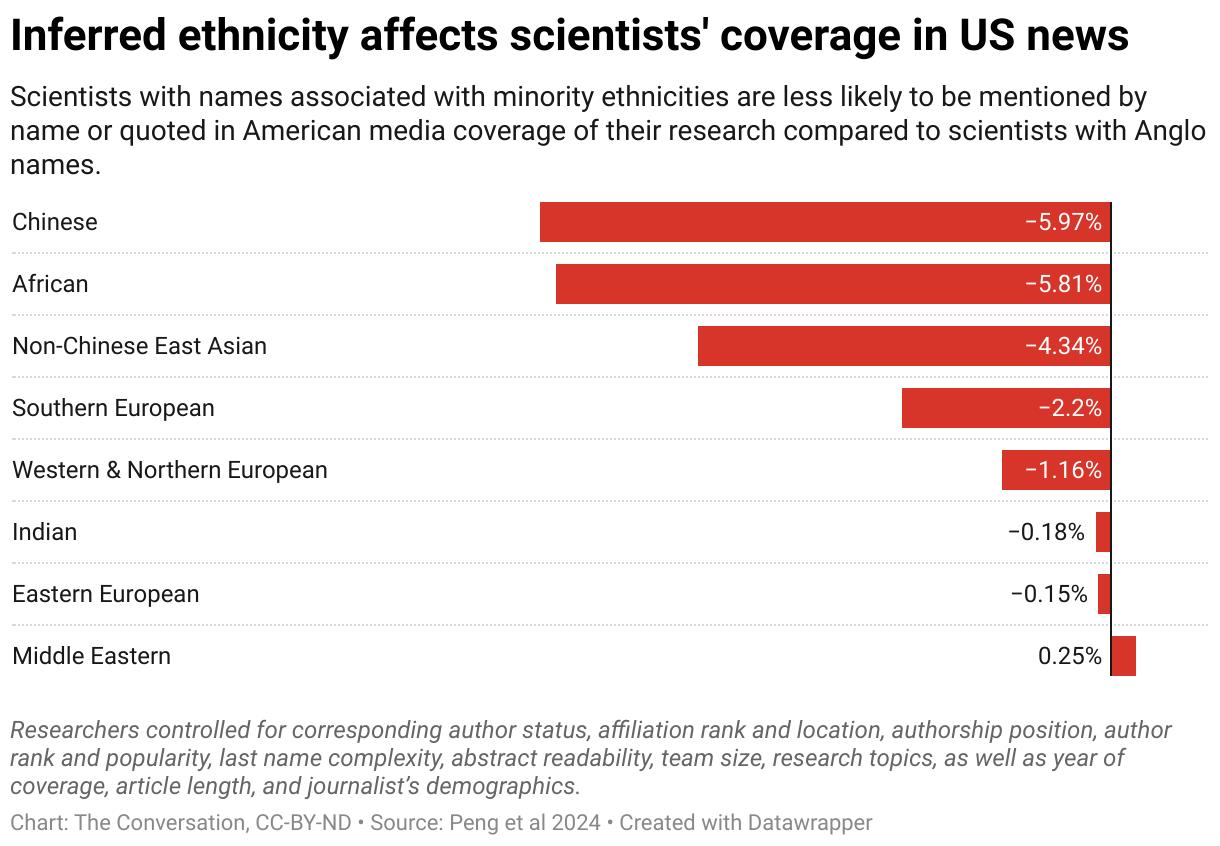

Inferred ethnicity affects scientists' coverage in US newsScientists with names associated with minority ethnicities are less likely to be mentioned by name or quoted in American media coverage of their research compared to scientists with Anglo names.

Chinese

−5.97%

African

−5.81%

Non-Chinese East Asian

−4.34%

Southern European

−2.2%

Western & Northern European

−1.16%

Indian

−0.18%

Eastern European

−0.15%

Middle Eastern

0.25%

Researchers controlled for corresponding author status, affiliation rank and location, authorship position, author rank and popularity, last name complexity, abstract readability, team size, research topics, as well as year of coverage, article length, and journalist's demographics.

This association is consistent even after accounting for factors such as geographical location, corresponding author status, authorship position, affiliation rank, author prestige, research topics, journal impact and story length.

And it held across different types of outlets, including publishers of press releases, general interest news outlets and those with content focused on science and technology.

Pragmatic factors and rhetorical choicesOur results don't directly imply media bias. So what's going on?

First and foremost, the underrepresentation of scientists with East Asian and African names may be due to pragmatic challenges faced by US-based journalists in interviewing them. Factors like time zone differences for researchers based overseas and actual or perceived English fluency could be at play as a journalist works under deadline to produce the story.

We isolated these factors by focusing on researchers affiliated with American institutions. Among US-based researchers, pragmatic difficulties should be minimized because they're in the same geographic region as the journalists and they're likely to be proficient in English, at least in writing. In addition, these scientists would presumably be equally likely to respond to journalists' interview requests, given that media attention is increasingly valued by US institutions .

Even when we looked just at US institutions, we found significant disparities in mentions of and quotations from non-Anglo-named authors, albeit slightly reduced. In particular, East Asian- and African-named authors again experience a 4 to 5 percentage-point drop in mention rates compared with their Anglo-named counterparts. This result suggests that while pragmatic considerations can explain some disparities, they don't account for all of them.

Sign up for one of our free newsletters

- The Daily ReportStart your day right with Asia Times' top stories AT Weekly ReportA weekly roundup of Asia Times' most-read stories

We found that journalists were also more likely to substitute institutional affiliations for scientists with African and East Asian names – for instance, writing about“researchers from the University of Michigan.” This institution substitution effect underscores a potential bias in media representation, where scholars with minority ethnicity names may be perceived as less authoritative or less deserving of formal recognition.

Reflecting a globalized enterprisePart of the depth of science news coverage depends on how thoroughly and accurately researchers are portrayed in stories, including whether scientists are mentioned by name and the extent to which their contributions are highlighted via quotes. As science becomes increasingly globalized, with English as its primary language, our study highlights the importance of equitable representation in shaping public discourse and fostering diversity in the scientific community.

While our focus was on the depth of coverage with respect to name credits, we suspect that disparities are even larger at an earlier point in science dissemination, when journalists are selecting which research papers to report. Understanding these disparities is complicated because of decades or even centuries of bias ingrained in the whole science production pipeline including whose research gets funded , who gets to publish in top journals and who is represented in the scientific workforce itself .

Journalists are picking from a later stage of a process that has a number of inequities built in. Thus, addressing disparities in scientists' media representation is only one way to foster inclusivity and equality in science. But it's a step toward sharing innovative scientific knowledge with the public in a more equitable way.

Hao Peng is a postdoctoral fellow in computational social science at Northwestern University .

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article .

Thank you for registering!

An account was already registered with this email. Please check your inbox for an authentication link.

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Most popular stories

Market Research

- Invromining Expands AI Quant Infrastructure To Broaden Access To Digital Asset Strategies

- BTCC Summer Festival 2025 Unites Japan's Web3 Community

- Argentina Real Estate Market Size, Growth, Trends & Outlook 2033

- United States Animal Health Market Size, Industry Trends, Share, Growth And Report 2025-2033

- Fitness App Market Is Expected To Reach USD 18.16 Billion By 2033 At CAGR 22.51%

- Latin America Mobile Payment Market To Hit USD 1,688.0 Billion By 2033

Comments

No comment