403

Sorry!!

Error! We're sorry, but the page you were looking for doesn't exist.

Too Many Languages? Multilingualism Leads to Conflict in Morocco

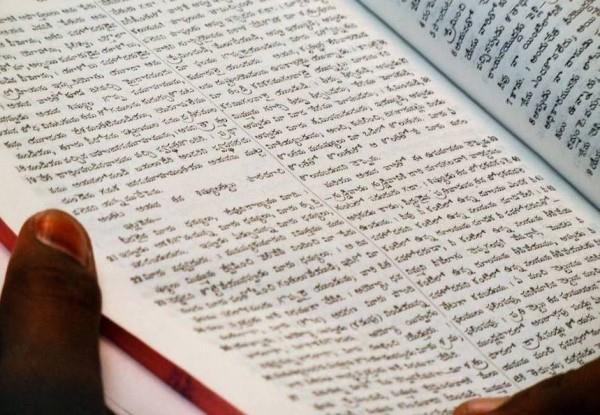

(MENAFN- Morocco World News) By Ossama Bziker Kenitra - Many believe that the language situation in Morocco is more of a conflict than an advantage. Most language conflicts stem from the unbalanced status allocated to each language in a single country. Language conflicts take place, most of the time, in multilingual countries such as Morocco. Its strategic location at the gateway between Africa, Europe, and the Middle East has caused Morocco to be influenced by multiple waves such as the Arabs, Spaniards, Portuguese, and French. Morocco has a variety of languages spoken within the country. The first group includes Moroccan Arabic and Tamazight (Berber), which are held in low esteem by society. The second group includes French and Standard Arabic, which are the languages of administration and are held in high esteem by Moroccans. This interaction between languages creates a realm for competition, which results in a class struggle, as Grandguillaume puts it (Saib, 2001: 5). Language Policy in Morocco In regard to the diversity of Moroccan languages, Zouhir argues that the Moroccan linguistic repertoire includes two groups. The first includes Moroccan Arabic and Tamazight, which occupies a vulnerable social status in Morocco. The second category includes French, Standard Arabic, and English. These languages are used in administration Dawn Marley argues that there are three languages that enrich Moroccan language repertoire: Tamazight, Arabic, and French. She thinks that these three languages are the ones that must be included in any discussion related to language issues (Marley, 2005). Read Also: Tamazight: Combatting 'Linguistic Terrorism' in Morocco Saib analyzes the linguistic situation in Morocco in a more detailed approach. He refers to the two languages that have native speakers and are the mother tongues of Moroccans, both inside and outside of Morocco. He says, 'Moroccan Arabic and Berber are the only varieties that are spoken natively' (Saib, 2001). Other languages, such as Standard Arabic, French, Spanish, and English, are limited to schools. Boukous thinks that there are competition and power struggles among languages as well as between the two groups of language (Zouhir, 2013). Another thing that Saib mentions is that policy-makers have favored the use of French against Standard Arabic as the most appropriate language for instruction in schools (Saib, 2001). To support his argument, Saib claims that the Royal Commission on the Reform of Education does not include the use of mother tongues (Tamazight and Moroccan Arabic), and he added that the policy is still the same today. Furthermore, Saib unravels some of the paradoxes, utilizing the figures from the 1994 Census. Saib notices that the Amazigh (Berber) population is estimated to be 38.64% of the total Moroccan population. If that is added to the number of Tamazight speakers dwelling in urban cities and outside of Morocco, it will push the percentage to reach 60%, as estimated by some Amazigh scholars (Saib, 2001). According to these figures, if correct, one can only notice that Tamazight is minimized even though the Tamazight language is a majority language (Ibid). One of the reasons behind minimizing the Tamazight language, Saib argues, is obviously political: The ethnocentric pan-Arabist political establishment, which has been repeating ad nauseum that Morocco is an Arab country and that Moroccans are Arabs, does not obviously want the Amazigh to know how many they are, hence their demographic weight, for fear that they may demand a political power corresponding to it (Saib, 2001:1) Read Also: Moha Ennaji Presents Anthropological Study of Morocco in 'The Olive Tree of Wisdom' The demographic weight obviously poses a threat to the elite's ideological plan. Moreover, Marley thinks that reinstating Arabic was a means of preserving Morocco's Arab-Islamic identity, and its epistemological break with Western ties. (Marley, 2005:1488). She also added that during the Arabization plan, people thought that it was a good move since they had never been exposed to foreign languages or Classical Arabic (Ibid). Saib states that the sociolinguistic situation of both Tamazight and Moroccan Arabic is inherently motivated by ideological and political intentions (Saib, 2001:4). Marley, following in the footsteps of Saib, argues that 'A powerful motivation behind the policy is the pursuit and maintenance of power: the 'élite' promote Arabization from virtuous ideological motives, but in the knowledge that French continues to be necessary for social and professional success' (Marley, 2005: 1489). Saib asserts that specialists in the field, who take into consideration sociolinguists' findings and literature, are the ones who should carry on language policy and planning (Saib, 2001). Language Conflict in Morocco The language situation in Morocco can be seen as 'simplex'; it is simple but complex at the same time. On one level, foreigners see multilingualism in Morocco as richness. On the other level, theorists like Saib see it as complex and unfair. When Arabization was first established by the Istiqlal-led first national government (1955-1956), it was based on purely political and ideological intentions (Saib, 2001). The sociolinguistic status assigned to Tamazight and Moroccan Arabic during independence was the work of the pro-Arabization 'nationalist' elite, who chose the language that suited their agenda (Ibid). 'They have been subjected to a consciously planned process of minorization and excluded from the school domain' (Saib, 2001:4). Read Also: Why the English Language Is Vital for the Future of Morocco Saib says that Tamazight and Moroccan Arabic were regarded as vernaculars that are considered stigmatized forms of speaking used in casual settings (Ibid). Marley argues that Tamazight language and culture are held in low esteem, and are regarded as 'synonymous with inferiority and ignorance' (Marley, 2005). Boukous says that an analysis of the sociolinguistic situation in North Africa reveals the hierarchy and classification of languages according to various ecological factors, such as the economy, politics, the marketplace, and technology (Boukous, 2008:35). When Morocco gained independence in 1956, several reforms took place in its linguistic policies. For Morocco to break with Western influence, it declared Classical Arabic as the official language of the country alongside the Arabization policy (Zouhir, 2013: 274). The purpose of Arabization was to bring the country together, but it did not respect the multilingual voices that inhabit Morocco (Zouhir, 2013: 274). Morocco implemented the same strategy that the French adopted during their colonization in Morocco. 'During the French occupation for 44 years from 1912 to 1956, French was imposed and instituted as the main language of instruction at all levels of education, and Arabic as a foreign language' (Redouane, 2016: 19). In fact, back in 1930, the French used Tamazight dialects and the Arabic vernaculars, through the 'Dahir berbère' (Berber Decree), to help divide the country in order to rule more widely (Redouane, 2016: 19). After the failure of Arabization, Grandguillaume saw 'Arabization as a class struggle' (Saib, 2001). Tamazight speakers started voicing their rights; it was time for a reform that could actually deliver solid results. Read Also: Six Things Students of Arabic Should Know before Starting Their Language Journey Years have passed searching for the absolute solution for the linguistic catastrophe Morocco has suffered. The Charter for Educational Reform, created in 2000, calls for a drastic linguistic change. Article 110 in the Charter states, 'Morocco will now be adopting a 'clear, coherent and constant language policy within education'. This policy has three major thrusts: 'the reinforcement and improvement of Arabic teaching', 'diversification of languages for teaching science and technology' and an 'openness to Tamazight' (Marley, 2005: 1489). Openness towards Tamazight is a huge jump towards inclusion. Although many might not see this step as being enough, at least it represents movement toward change and an admission that not all Moroccans are Arabs. As Berdouzi suggests (2000: 26), if the Charter delivers what it promised, young Moroccans will excel in Standard Arabic, as well as use it appropriately in different domains, and they will also excel in at least two foreign languages, which they will use in several contexts (Marley, 2005: 1490). Morocco has adopted many reforms in the past. Although these decisions by previous policy-makers were somewhat poor, they tried to adapt and form a linguistically-united Morocco. Regardless of their agendas and intentions, the changes and reforms that have occurred in Morocco are solid steps toward changing what went wrong and preventing it from happening in the future. Challenges will always present themselves. For example, Tamazight is limited to the elementary level and Standard Arabic is supposed to be used in higher education. Moreover, the Charter suggested that Morocco has opened up to foreign languages without specifying what languages. This leaves the foreign languages in a state of rivalry. However, this does not mean change stops here or that it will take place overnight. This process of recreating policies and correcting the mistakes of the past is a healthy one. Morocco has to learn from its mistakes and evolve toward a better future. The views expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect Morocco World News' editorial views. © Morocco World News. All Rights Reserved. This material may not be published, rewritten or redistributed without"

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment