From Concrete Walls To Living Edges, Here's How Riverside Habitats Are Being Restored Along The Thames

Much of this change happened in the Victorian era. The Thames embankment straightened and hardened the river's edge, severing the natural connection between land and water. Today, barely 1% of those original intertidal habitats - the shallow zones between the low and high tide mark - remain. But while the physical landscape has continued to shrink, the condition of the water has taken a very different path.

Since the 1960s, water quality has improved dramatically, and more than 125 fish species have been recorded in the Thames river system. Some even spawn in the Thames. With stable oxygen levels and declining pollution, the river has made an impressive biological recovery - but not a physical one. Fish have returned, but the habitats they depend on have not. With so few natural areas left today, young fish have far fewer places to feed and grow than they once did.

Restoring life at the edgeTo counter this loss, new aquatic habitats have been created across London over the past 25 years. The Estuary Edges project - led by the Thames Estuary Partnership with the Environment Agency and the Port of London Authority - shows how to soften hard riverbanks and make space for wildlife.

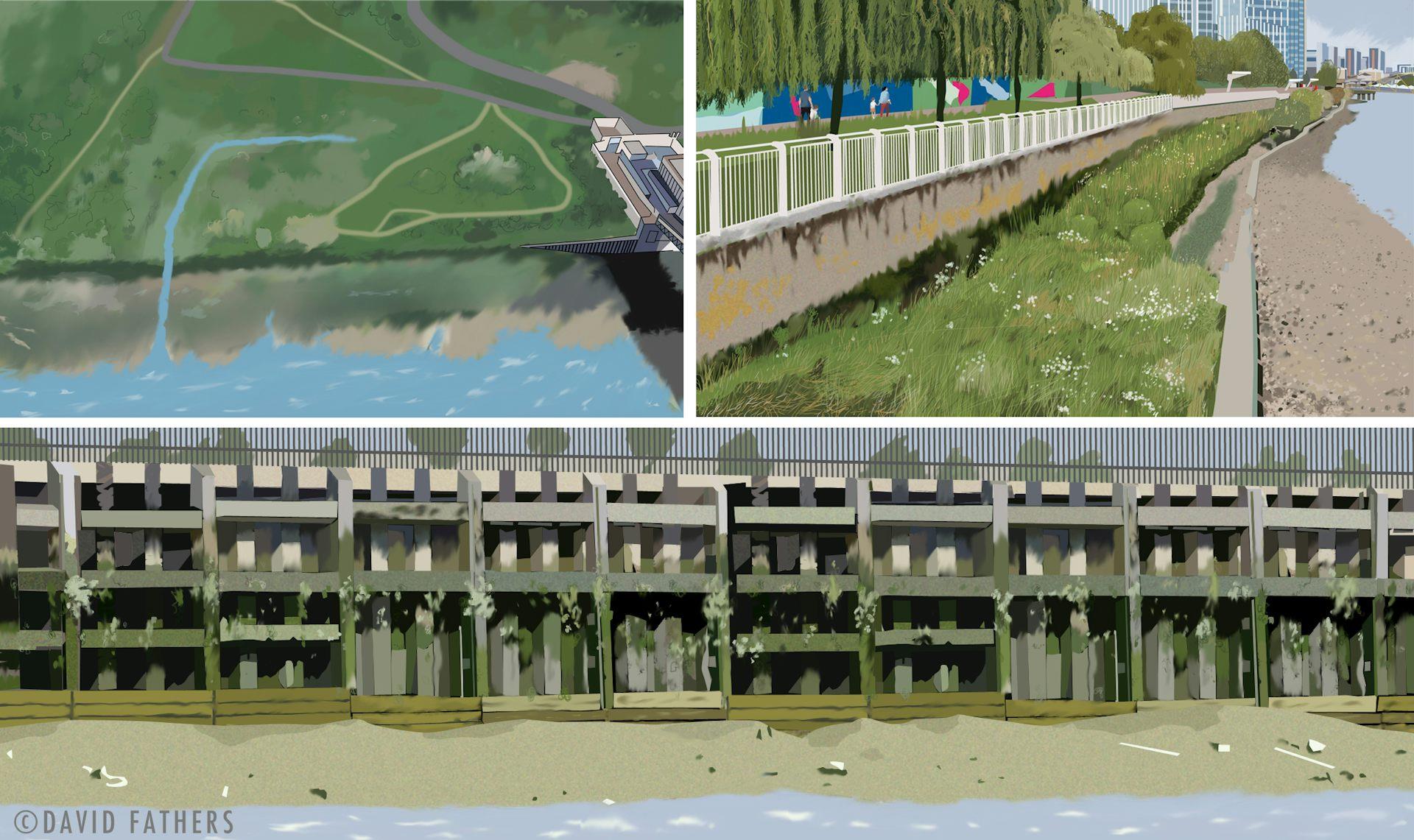

Engineered intertidal habitats - Top left: setback; Top right: vegetated terrace; Bottom: vertical wall. Author provided (no reuse)

These created or“engineered” habitats come in many shapes and forms. Some are“setbacks”, where parts of the river wall are opened or moved back to allow tides to flood naturally. Others are gently sloping vegetated terraces. These are sections of hard wall or steep bank that have been reshaped and planted with aquatic and saltmarsh plants to recreate a more natural edge.

Even vertical walls can be improved by adding ledges and textured surfaces. These features give aquatic wildlife places to cling, feed and shelter.

Between 2017 and 2023, nine“estuary edges” sites were surveyed, from Barking Creek to Wandsworth in London. Using specialised nets, more than 1,000 fish were recorded - including gobies, seabass and the critically endangered European eel. Almost all were juveniles, showing that even small, vegetated areas can shelter young fish in the heart of London. The surveys also showed that design and time matter. Habitats with gentle slopes, channels and good water flow supported more fish. Sites with barriers or poor drainage often trapped water - and fish - on the falling tide.

At Greenwich Millennium Terraces, an area of the peninsula that was redeveloped in 1997, a natural drainage channel formed over the years. By 2023, the site supported mullet, flounder and many eels. At Barking Creek, a tidal channel that reformed after reed overgrowth restored fish access and increased diversity. The neighbouring setback site, built in 2011, kept water flowing throughout the tide and consistently supported gobies, seabass, flounder and eels.

Juvenile European eel. Author provided (no reuse)

These examples show that habitat creation works - but they also highlight significant knowledge gaps. Compared with decades of research on water quality, studies on habitat function remain limited, especially across different habitat types and levels of human impact.

Further downstream, the Transforming the Thames project is now scaling up restoration. Led by the Zoological Society of London, it focuses on the outer estuary, where there is more space to restore and reconnect habitats.

Together, Estuary Edges and Transforming the Thames offer complementary approaches to habitat recovery: creating new habitats along the urban river edge while restoring those lost across the broader estuary.

Effra Quay, a newly created public space at Vauxhall, London. Author provided (no reuse)

This connection underpins my PhD research. I study how fish use natural, degraded, created and restored habitats across the Thames. By combining environmental DNA with net surveys, diet analysis, and stable isotope techniques, I explore how fish feed, move and interact with different habitat types. This helps reveal how these habitats support fish - and how fish respond as restoration progresses.

Creating and restoring habitats is not only about helping fish and other wildlife. Shallow, plant-rich edges stabilise sediments, absorb waves, improve water quality and strengthen climate resilience. They also create peaceful“blue havens”: places where people can reconnect with the river.

Once declared“biologically dead”, the Thames has made a remarkable comeback. Its revival story, however, is still being written.

Don't have time to read about climate change as much as you'd like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation's environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 47,000+ readers who've subscribed so far.

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment