404 Not Found: How Internet Shutdowns Impact South Asians

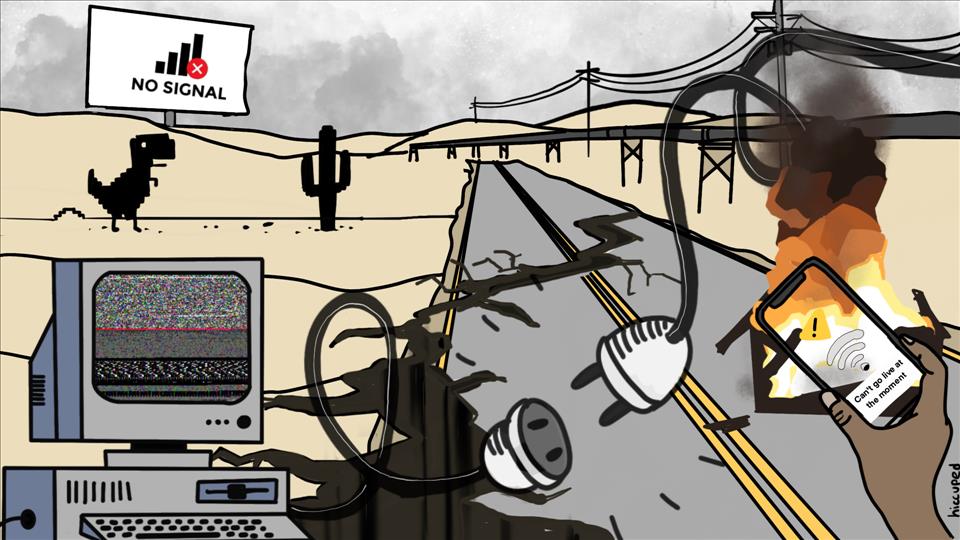

Across the world, social media has emerged as a means to collectively voice opinion and advocate for causes since the early 2000s. In South Asia, where internet penetration rates and mobile phone usage are some of the highest in the world, the platforms have been instrumental in democratising freedoms of speech and expression too.

The data speaks for itself. In India, over 70 percent of the population was using the internet as of 2024 data by International Telecommunication Union. In Bangladesh, that rate came up to 44.5 percent in 2024. The mobile broadband subscriptions stand at 899 million users for India and 98 million users in 2024. Looking at data from 2023 for Sri Lanka and Pakistan, we see the connectivity rate at 51.2 percent and 27.4 percent, respectively. The active mobile broadband subscriptions are at 73.5 per 100 people for Sri Lanka and 55.1 per 100 for Pakistan, as of 2024.

At the same time, the digisphere has created a new landscape for non-elite civic participation in everyday politics and political activism, wrote Dr Ratan Kumar Roy, a media studies professor from Bangladesh based in India, in his white paper on digitisation and civic participation.“Politics in the digital age is often subtle and takes on forms different from traditional political activism. This can include liking, sharing or commenting on political content, which can collectively have a large impact,” Roy notes in the report.

According to digital rights group Access Now, South Asia has seen some of the world's leading internet shutdowns for over six consecutive years until 2024. In their 2024 report, they note that India witnessed 116 internet shutdowns in 2024 and over 500 in the last five years.

Mishi Chaudhary, the founder Software Freedom Law Center (SLFC) in India recalls two types of internet shutdowns: Preventive – that are imposed in anticipation of an event that may require the internet to be suspended by the state – and reactive, which are imposed to contain ongoing law and order situations. Internet shutdowns can take various forms, from blocking of certain websites to partial or full telecommunication and internet shutdowns.

“Internet shutdowns are the easiest tool in the toolbox for governments to control the flow and dissemination of information,” Chaudhary tells Asian Dispatch.“Although no evidence has ever been presented about the effectiveness of shutdowns, state authorities, fearful of the ease of organisation via the internet, are quick to use this blunt instrument of state power.”

In this piece, Asian Dispatch mapped 397 shutdowns between July 2019 and 2024 in India, Sri Lanka, Pakistan and Bangladesh out of which shutdowns in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka stand out. This data doesn't include Afghanistan, Bhutan, the Maldives and Nepal, where internet shutdowns of this measure have not been documented.

Internet shutdowns have tangible real-world costs. In 2024, Pakistan's economy was estimated to have lost between $892 million and $1.6 billion, according to the Information Technology and Innovation Foundations, a Washington-based think tank working on science and technology policy. In 2018, Sri Lanka faced an estimated $30 million loss due to similar measures, as reported by NetBlocks. The figures for India in 2024 stand at $322.9 million, as per the report by Top10VPN.

Robbie Mitchell, Senior Communication and Technology Advisor for the Internet Society, a global charitable organisation, says that information blackouts resulting from internet shutdowns can, in fact, result in increased violence. He elaborates further by adding that violent tactics of protest are less reliant on effective communication mechanisms and thus they could substitute non-violent protests that rely on the internet for planning and organization in the cases of internet shutdowns.

“In addition, internet shutdowns tend to attract international attention and create pressure on countries that undertake them. This relates to the so-called 'Streisand effect,' where the attempt to silence voices or hide information leads to the unintended consequence of bringing more attention to them,” Michelle says.

Left in the Dark

Mandeep Punia, a 30-year-old journalist from India, says that any internet shutdown causes a“fear of the unknown” in the society. Punia has experienced shutdowns first during the 2016 Jat community reservation protests, as well as the 2019 shutdown in Kashmir during the abrogation of article 370, among others. The most recent internet shutdown in India was in the state of Haryana in August 2025, as recorded by the internet tracker maintained by SLFC.

About 3,000 kms away, in Sri Lanka, Oshadi Senanayake, a civil society member and social worker, recalls the communication shutdown during the anti-Muslim violence in Sri Lanka in 2018. The series of violence saw the imposition of a nationwide state of emergency as Sinhalese-Buddhist crowds attacked Muslims and their establishments in the city of Kandy.“When the means of communication were restricted, it was very difficult,” she tells Asian Dispatch.“We were all in the dark, no one knew what was going on and there was no way to find out either.”

The similarity in these narratives connects the dots across South Asia on how internet shutdowns impact people.

In 2024, Pakistan invoked the region's most recent shutdowns, which was done to curtail mass uprising in support of jailed former prime minister Imran Khan. This was one of the 17 shutdowns Pakistani people faced in the last five years, as per data collected by Asian Dispatch.

The same year, in July, Bangladesh saw mass protests by university students over government jobs, which eventually upended Sheikh Hasina's 21-year rule. Her government resorted to internet shutdown in order to curb the organised movement. Over 1,000 people were killed during the protests, as per a report released by the interim government led by Nobel Laureate Mohammad Yunus.

At the same time, Asian Dispatch learned of students finding ways to circumvent the internet blackout, specifically by urging the residents to open their Wi-Fi networks, either by removing passwords or using“123456,” to support the movement. Shahriyaz Mohammed, a student at the University of Chittagong, and Raihana Sayeeda Kamal, another student based in Dhaka, confirmed that such appeals were made. According to Roy, who is also a former media studies professor at BRAC University in Bangladesh, this appeal drew widespread response, with many complying.

At the same time, the communication blockade disrupted the academic and professional prospects for many. Kamal said that she graduated last July and was supposed to apply for her postgraduate work permit in Canada.“I couldn't do it. I was out of touch from Canada. It hampered my job search and communications with my professors, and delayed my application,” she tells Asian Dispatch.

Mohammed, who lives in Chattogram, the second largest city of Bangladesh, says that internet cuts take place anytime, and that the Internet Service Providers (ISP) do not give any prior notice.

“The internet is the most necessary thing for my occupation and also for my study,” he says. However, due to these shutdowns, he wasn't able to communicate with his office or get any updates from other parts of the country during the protests which hampered work for him as a budding reporter.

Controlling the NarrativeIn 2019, India abrogated Article 370 of the Indian Constitution, which accorded special privileges to the region of Jammu and Kashmir. Along with the announcement came a sweeping communication blockade in order to curb disruptions due to anticipated unrest . The blockade in the region lasted 18 months prior to the services being fully restored. In all, the region experienced 213 days of no Internet and 550 days of partial or no connectivity, as noted by the Internet Society .

“Due to COVID-19, everyone knows what a lockdown looks or feels like. But it was only worse in Kashmir as there was not a restriction to physical spaces but also to virtual spaces,” Sayma Sayyed*, a student at a leading university in India, tells Asian Dispatch on condition of anonymity.

The situation, she added, resembled a pre-digital era, with no internet or mobile reception, forcing people to travel several kilometers just to check in with their loved ones.

The lack of internet creates a void of information in the society, says Sayyed*, a resident of Baramulla in Kashmir.“When I had to fill my form for competitive exams, students had to rush to government offices to do so,” Sayyed added.“So I went to the District Commissioners office to fill my form which is when I realised something has happened. Something I could do on a leisurely day became such a big task.”

Within India, the Union territory of Jammu & Kashmir holds the record of the highest number of shutdowns in the country.

Another student from the valley, who also spoke to Asian Dispatch on condition of anonymity, highlighted the psychological impact of such situations.“You don't feel normal in places outside Kashmir,” the student said.“When I shifted to Delhi for further studies, I was confused as I was able to carry out my studies without any restrictions. I expressed this to my friends and they, too, agreed with the lack of restrictions. It felt jarring to someone who has seen so many curfews and internet blackouts.”

In Bangladesh, Shamim Hossen, a 28-year-old humanitarian worker and the reporting officer at Muslim Hands International, a charitable organisation, highlights how those solely reliant on mobile data were completely cut off.“I use mobile internet and data, and when I am in my office, I use Wi-Fi. But during the internet shutdown, our office was closed so I have no experience using Wi-Fi during that time,” she tells Asian Dispatch.

Sri Lanka has seen the use of full internet shut downs as well as partial restrictions such as curbing access to social media websites for a certain duration. Incidents such as the Easter bombings in 2019 which saw serial blasts on multiple public and religious sites in Colombo, to the economic crisis of 2022 to the Presidential elections in 2023 saw the use of such measures. The country has seen 5 shut downs from 2019 to 2022, as per data collected by Asian Dispatch.

Amarnath Amarasingam, Assistant Professor at the School of Religion, Department of Political Studies, at Queen's University in Canada, told Asian Dispatch about the relation between misinformation and shutdowns.“In Sri Lanka, when social media was blocked, citizens turned to alternative, less reliable sources,” he says.“These shutdowns made it difficult for credible journalists and activists to fact-check information, leading to a situation where rumours and conspiracy theories filled the void. In countries with ongoing communal tensions, the spread of false rumours can lead to real-world violence against civilians as well.”

Highlighting the broader implication of using internet shutdowns to control dissent, Amarasingam adds:“Internet shutdowns have significant human rights implications, especially around issues like freedom of speech and access to information. Shutting down internet services curtails individuals' ability to express dissent, participate in protests, or even access vital services such as health and education. All of this, of course, will impact marginalised communities more than others.”

“In Sri Lanka, these shutdowns particularly affect communities with fewer alternative sources of information and who rely on mobile internet for basic services. In the former war zones in particular, these alternative sources of information are key for receiving information that is not curated by the government.”

Disrupting Normalcy

“My clients outside of Peshawar think that people from the region do not work properly due to internet restrictions coming up now and then. We had in fact replied to messages but they would reach one to two hours later, which affected our credibility.”

This is the ordeal of Sufi Ali, a 35-year-old IT officer from Mardan, located in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) province of Pakistan. Pakistan has recorded 35 shut downs between July 2024 to July 2019, according to the Asian Dispatch analysis. These include blocking the internet in response to protests such as the ones in support of former Prime Minister Imran Khan in 2022 to allegations of throttling with the internet speed by the government during the testing of speculated possible internal firewall.

“Along with the professional, personal life also gets affected,” adds Aftab Mohmand, a 44-year old senior journalist from Peshawar, the capital city of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Mohmand adds that usually, one can circumvent restrictions through VPN or Wi-Fi. But in Peshawar, there is no such facility. Four of the 35 shutdowns Asian Dispatch has documented from 2019 to 2024 for Pakistan were in KP.“VPN data is monitored and it can be dangerous too,” says Mohmand. Since 2014, he has been using the phone to make reels, create reports and record everything using the internet. .

Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) are often used to bypass shutdowns or access regionally blocked websites. But Mohmand notes that they significantly slow down internet speeds.

Journalists from India, Sri Lanka and Pakistan told Asian Dispatch that these restrictions make it nearly impossible to verify information for accurate reporting.

“I am a journalist so whenever we go out for conflict reporting, we face [internet shutdown],” says Punia, the rural journalist from India.“But the worst aspect of that is that our [media portals] are also shut down.

His concerns are mirrored by Sandun, a freelance journalist based in Sri Lanka. Talking about covering the 2018 anti-Muslim violence, she says the internet shutdown made their job even more difficult.“We treated every piece of news with suspicion and nothing could be verified. The officials were too silent or evasive and we didn't have anyone on the ground. We felt like we would risk peddling misinformation,” she says

On July 19 alone – the day Sheikh Hasina's ousted regime enforced an internet blackout – at least 148 people were killed by law enforcement agencies, according to a report by the International Truth and Justice Project (ITJP) and Tech Global Institute.

CIR also identified two "peaks" in violence. The first was on July 18, where killings amounted to a massacre. It all started with the killing of a protester called Abu Sayeed, in Rangpur district, on July 16, which was captured in a now iconic image of him spreading his hands in front of the police force. The second peak in violence was on August 5, the day Hasina resigned and fled to India.

Both these peaks in violence also correspond to internet shutdowns, as Asian Dispatch has investigated.

The Policy Pitfalls

South Asian governments often cite national security and misinformation as reasons for internet shutdowns. However, these terms are frequently undefined or vaguely worded in legislation and policy, prompting global experts to raise concerns about their potential misuse.

In the absence of any explanations by government arms on the reasons behind these moves, speculation is rife. For instance in India, internet shutdowns are governed under the Temporary Suspension of Telecommunication Services Rules, 2024, which, under clause 3, explicitly states that the reason for such measures needs to be released in writing. However, these orders are seldom found in the public domain..

In Pakistan, the legal backing of shutdowns is murky as the Pakistan Telecommunications Authority (PTA) also recently highlighted this legal uncertainty. Numerous laws are speculated at play here, with most shutdowns being informed by PTA, the body responsible for establishing, maintaining and operating telecommunications infrastructure in Pakistan, via orders for enforcement by the Interior Ministry. Other than these orders it is believed that Section 54(3) of Pakistan Telecommunication (Re-organization) Act, 1996 is used for such shut downs, which has been ruled against by the Islamabad High Court in 2018. The opacity of such measures is widely recognised by activists and advocacy organisations in the country as well as globally.

Recently, Pakistani journalist Hamid Mir filed a petition in Islamabad High Court, requesting for clarity on why the internet speed in the country were significantly lagging in the past few months, leading to even voice notes or multimedia on WhatsApp not reaching receivers. The petition comes at a time when speculations are rife about the government installing a“fire wall” that would prevent free and open use of the internet in Pakistan.

Other laws in Pakistan, such as the Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act, 2016 (PECA) under its 2025 amendment-equipped section 26(A) criminalise intentional dissemination of false information in the country. 'Fake news' is also the basis of many internet shutdowns, thereby hinting at the indirect use of the act for enforcing such measures.

Sri Lanka, too, sees a similar trend in a mix of non-specific regulations being used to curb internet and social media access in the country. Orders to the Sri Lankan Telecommunications Regulations Commission by the Ministry of Defense have been seen as ways of enforcing such curbs. Reasons for shutdowns range from curbing the spread of misinformation, to stopping demonstrations such as during a state of emergency.

Amarasingam says that the absence of official communication during internet shutdowns often leads to an information vacuum, which can fuel misinformation.

“The problem is that in authoritarian contexts, misinformation merely means critiques of the ruling party. And 'terrorism' often just means agitation against the government. And so, these terms are weaponised to curtail fundamental rights. In these contexts, shutdowns may hinder the spread of accurate information, create distrust, and deepen existing societal divisions,” she says.

In India, the law is clearly laid out but often not applied consistently. For this, Chaudhary of SLFC says that the civil society has to constantly approach the courts to enforce their rights.“Time period of shutdowns are extended continuously despite limitations imposed by law. Law requires proportionality,” Chaudhary says, adding that the proportionality of these actions is far more than required for the general good.

“Can shutting down the entire system of social communications and completely crashing the payments economy for months be 'proportional' to the necessary problem of preventing the incitement of intercommunal riots? If this government intervention is the 'least restrictive means,' what are the other more restrictive means the government would not be allowed to use?” Chaudhary asks.“The mind boggles.”

Mitchell from the Internet Society adds further context to the consequences of these actions:“Internet shutdowns tend to attract international attention and create pressure on countries that undertake them. This relates to the so-called Streisand Effect, where the attempt to silence voices or hide information leads to the unintended consequence of bringing more attention to them.”

Digital Rights are Human Rights

When asked whether they were informed prior to internet shutdowns, there's an astounding“no” from those interviewed for this piece.

Numerous international statutes reaffirm that the internet is an indispensable part of human rights. The United Nations Human Rights Council enshrines this in Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which“protects everyone's right to freedom of expression, which includes the freedom to seek, receive and impart information of all kinds, regardless of frontiers.” Restrictions to right to freedom of expression are only permissible under article 19(3) of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, although it notes:“When States impose internet shutdowns or disrupt access to communications platforms, the legal foundation for their actions is often unstated.”

In India, on two separate instances – by the High Court of the state of Kerala and then the Supreme Court – access to the internet has been declared a fundamental right under the Indian constitution.

“In India, the law is clearly laid out but often not applied consistently. adds Choudhary of SFLC.

In Bangladesh, a similar trend exists. Asian Dispatch spoke to students and young professionals who didn't receive any prior intimation of internet shutdown orders in the last one year. The trend is to slow down the internet, and then slowly revoke access fully, says Kamal, from Bangladesh.

Noting the impact of shutting down the internet, Michelle says:“Internet shutdowns have far-reaching technical, economic, and human rights impacts. They undermine users' trust in the internet, setting in motion a whole range of consequences for the local economy, the reliability of critical online government services, and even the reputation of the country itself. Policymakers need to consider these costs alongside security imperatives.”

While law governs social media and not internet shutdowns directly, it is worth noting that the negative effects of problematic regulations become yardsticks for regimes that govern a similar cultural and social landscape.

“It also stops people from both demanding and empowering government action to protect its people,” Chaudhary adds. “Shutdowns don't create the social and political will to safeguard our people, but rather a cloak for the government to hide its shame.”

Punia, the journalist from India, agrees and adds that freedom of speech and expression are never absolute.“They are only useful until one has to show them as democratic for indexes and rankings and gain marks there,” he says.

These are just a few examples of the broader impact experts point to. Given the concerns raised by individuals like Sayyed in India and Hossen in Bangladesh, a critical review of both the shutdowns and the frameworks enabling them is long overdue. Access restrictions need to be brought to the fore and the internet needs to be given a fair chance to make a case for its freedom.

Note : Kaif Afridi from Tribal News Network (an Asian Dispatch Member) and Rukshana Rizwie from Asian Dispatch, Sri Lanka, contributed to the report. The data has been collected by Abdullah Al Soad from Asian Dispatch, Bangladesh.

*The person's name has been changed to protect their identity, upon their request.

**Here, we account for all such instances as internet shutdowns, as blocking even a part of the internet is hampering communication for its users. Our methodology for data collection was to find reports by the media or advocacy organisations between Jan 2019 to Dec 2024 on internet shutdowns in India, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, and Bangladesh.

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment