Has France Truly Lost Africa-Or Can It Still Find A Way Back

(MENAFN- The Rio Times)

With French bases shuttered across the Sahel and rivals from Beijing to Moscow stepping in, Paris is scrambling to reinvent itself on a continent it once dominated. Is there a path back-on Africa's terms?

When Senegal's President Bassirou Diomaye Faye stepped onto the red carpet at the Élysée on August 27, the symbolism was hard to miss.

For the first time in more than six decades, France had no permanent military base left in West Africa.

Yet here was Faye, speaking not of rupture but of a reset. France's armies have been told to leave; ties, however, are not entirely severed.

The question is whether that reset is plausible-or whether France has already lost the continent to hungrier rivals.

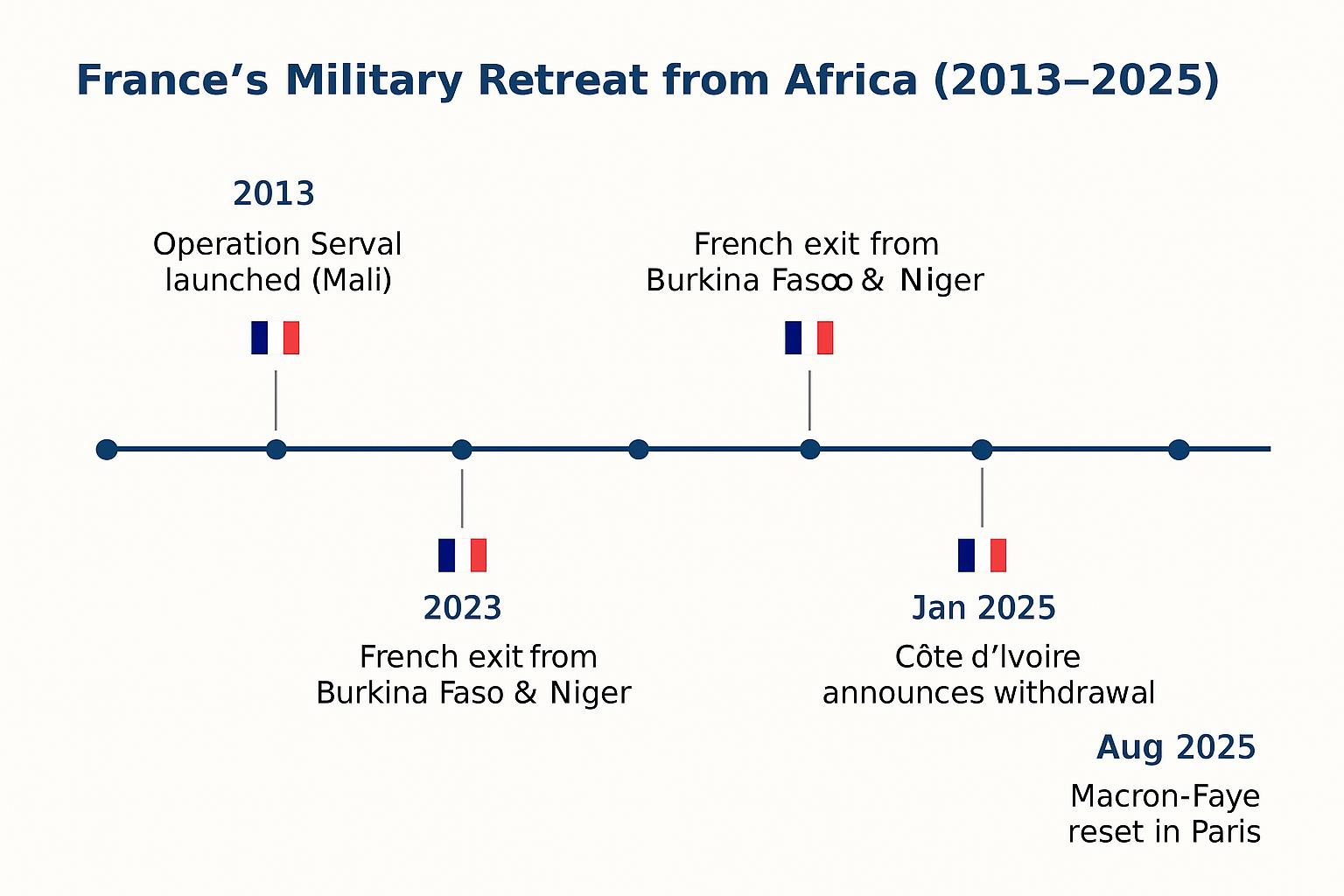

The Fall of the Old Order The retreat has been swift. One by one, countries once considered France's closest partners expelled French troops. Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger led the charge, accusing Paris of failing to defeat jihadists while meddling in politics. Crowds in Ouagadougo and Niamey burned French flags and waved Russian ones. By early 2025, Chad and Côte d'Ivoire-longtime pillars of French influence-joined in, ordering troop withdrawals. Finally, in January, Senegal followed suit, fulfilling Faye's campaign promise that“sovereignty does not allow foreign bases.” This was more than a military redeployment. It marked the collapse of a post-colonial system often dubbed Françafrique: France as Africa's default policeman, banker, and political sponsor. The end came not because France chose to leave, but because African publics and leaders forced its hand. Decades of grievances-colonial massacres, the CFA franc currency, the perception that Paris propped up compliant strongmen while reaping Africa's resources-erupted into open rejection. Even Macron's attempts to break with the past backfired. His calls to end Françafrique and listen to African youth were overshadowed by his blunt complaints that Africans were ungrateful for France's anti-terror campaigns. “The paternalistic 'big brother' role,” one African diplomat remarked dryly,“was alive and well in his tone.”

What Went Wrong

Beyond Francophone Africa What is happening in Francophone Africa echoes wider trends. In Anglophone Uganda, courts this year ordered colonial-era British statues torn down. In Ghana, voices call for a review of military cooperation with the United States. Lusophone states like Angola and Mozambique long ago shifted from Portugal to China and Brazil as partners. Across Africa, colonial ties are being questioned, and sovereignty is the watchword. France's loss, in other words, is part of a continental wave of decolonization. The difference is that France had held on longest-and so had the most to lose.

Conclusion Has France lost Africa? It has certainly lost its empire-its privileged status as gatekeeper and gendarme. That era is over. But Africa is not France's to lose or win; it belongs to Africans. France can still be relevant if it accepts that reality. If it offers fair trade, real investment, and respect for sovereignty, it may yet remain a valued partner-though never again the dominant one. The alternative is irrelevance, ceding the field to China, Russia, Turkey, and others. At the Élysée this August, as Macron and Faye discussed archives, trains, and trade, one thing was clear: the age of Françafrique is gone. What comes next will depend less on France's nostalgia than on Africa's choices. “Sovereignty does not allow foreign bases.” - Bassirou Diomaye Faye

The Fall of the Old Order The retreat has been swift. One by one, countries once considered France's closest partners expelled French troops. Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger led the charge, accusing Paris of failing to defeat jihadists while meddling in politics. Crowds in Ouagadougo and Niamey burned French flags and waved Russian ones. By early 2025, Chad and Côte d'Ivoire-longtime pillars of French influence-joined in, ordering troop withdrawals. Finally, in January, Senegal followed suit, fulfilling Faye's campaign promise that“sovereignty does not allow foreign bases.” This was more than a military redeployment. It marked the collapse of a post-colonial system often dubbed Françafrique: France as Africa's default policeman, banker, and political sponsor. The end came not because France chose to leave, but because African publics and leaders forced its hand. Decades of grievances-colonial massacres, the CFA franc currency, the perception that Paris propped up compliant strongmen while reaping Africa's resources-erupted into open rejection. Even Macron's attempts to break with the past backfired. His calls to end Françafrique and listen to African youth were overshadowed by his blunt complaints that Africans were ungrateful for France's anti-terror campaigns. “The paternalistic 'big brother' role,” one African diplomat remarked dryly,“was alive and well in his tone.”

“France failed us; Russia respects us.” - Malian officer

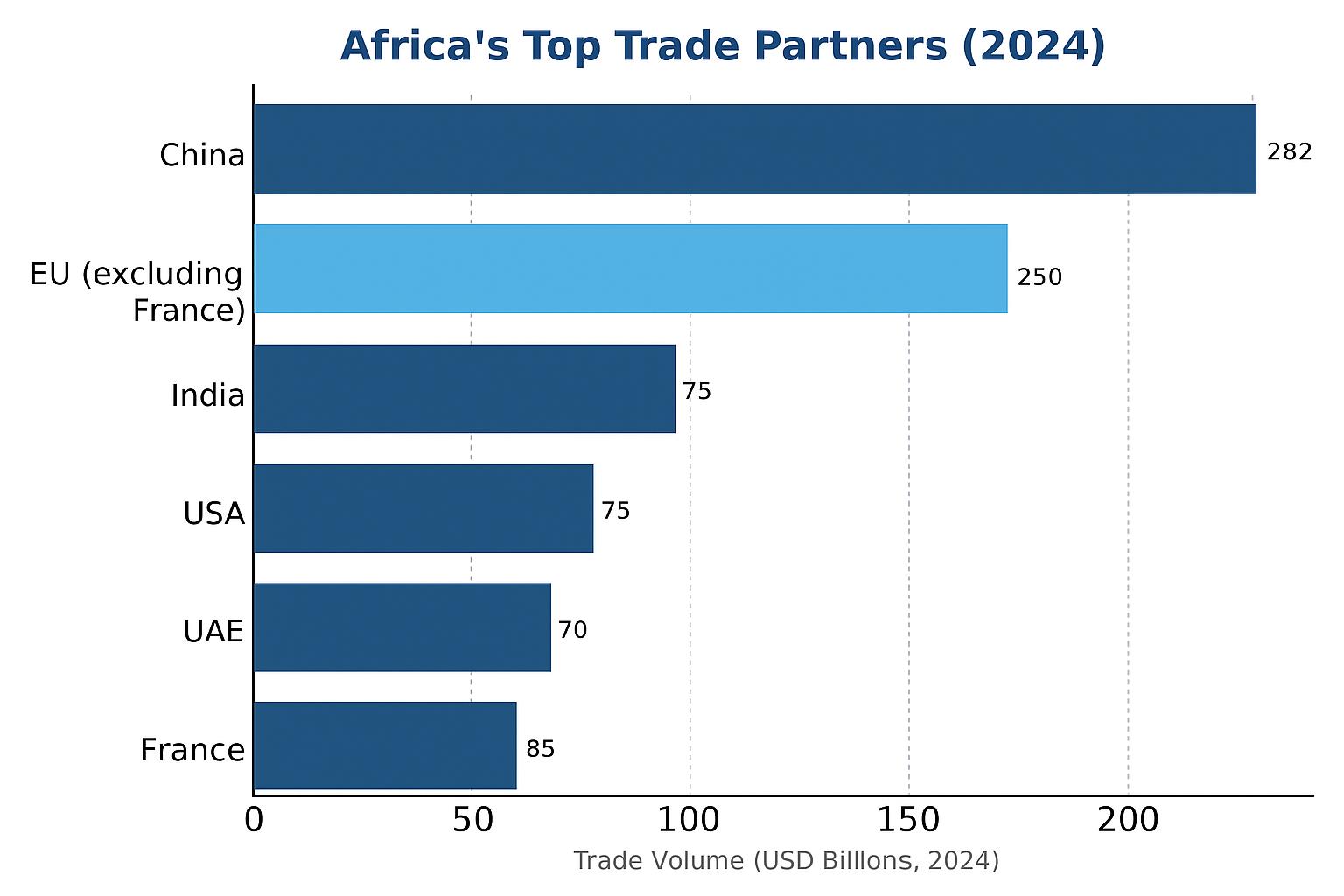

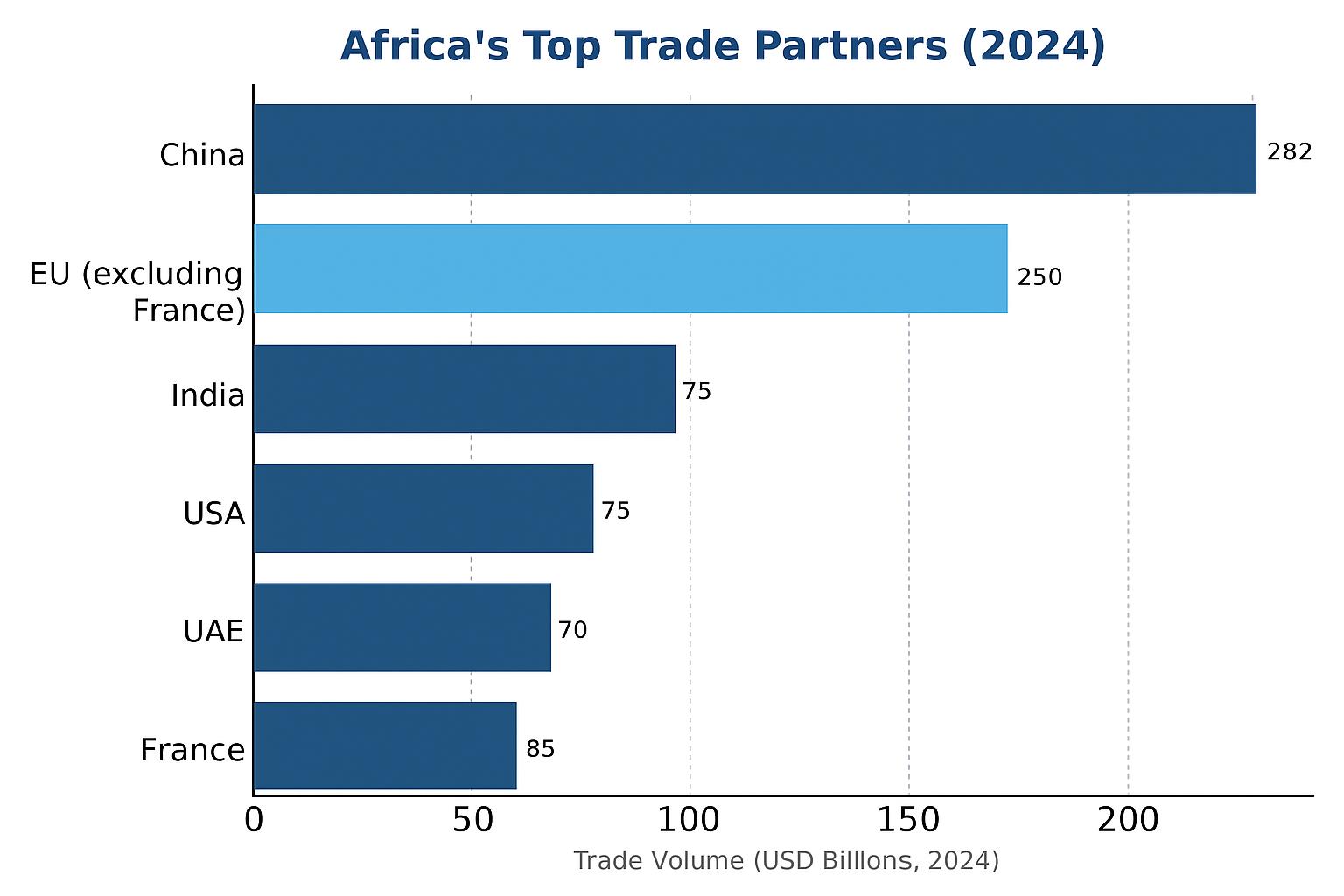

Rivals Filling the Vacuum As France withdrew, others rushed in. China has quietly become Africa's largest trading partner, with commerce surpassing $280 billion. In Abidjan, Chinese firms are building highways and ports once financed by French banks. In Dakar, a new sports stadium gleams with Beijing's backing. Unlike Paris, Beijing offers loans with few political conditions. The result: France's economic dominance has been eclipsed. Russia , though economically modest, has seized the security space France abandoned. In Mali and the Central African Republic, Wagner mercenaries-now rebranded as the“Africa Corps”-patrol cities and guard leaders. Moscow sells arms, spreads disinformation, and positions itself as Africa's ally against“neo-colonial” powers.“France failed us; Russia respects us,” a Malian officer declared this year. Turkey has expanded its footprint with a mix of religion, trade, and military hardware. Turkish drones are now used by several African armies. Mosques and cultural centers built with Ankara's support dot the Sahel. President Erdoğan casts Turkey as a Muslim partner that understands African sovereignty better than Europe. The Gulf states are also present: Dubai's DP World operates West African ports, Qatari funds build hotels and universities, Saudi money supports schools and agriculture. Where French companies once held sway, Emirati and Chinese investors now bid higher and faster. In this crowded marketplace, France is just another player.

What Went Wrong

-

Security: Operation Barkhane failed to stem violence; millions were displaced as insurgencies spread.

Economics: The euro-pegged CFA franc and market dominance of French firms symbolized tutelage rather than partnership.

Politics: A history of backing friendly incumbents, and refusals to recognize new juntas popular at home, fed charges of hypocrisy.

Diplomacy: Messages about gratitude landed as lectures in an era of assertive sovereignty.

Beyond Francophone Africa What is happening in Francophone Africa echoes wider trends. In Anglophone Uganda, courts this year ordered colonial-era British statues torn down. In Ghana, voices call for a review of military cooperation with the United States. Lusophone states like Angola and Mozambique long ago shifted from Portugal to China and Brazil as partners. Across Africa, colonial ties are being questioned, and sovereignty is the watchword. France's loss, in other words, is part of a continental wave of decolonization. The difference is that France had held on longest-and so had the most to lose.

“France must be just another partner, not Africa's guardian.” - Analyst, IFRI

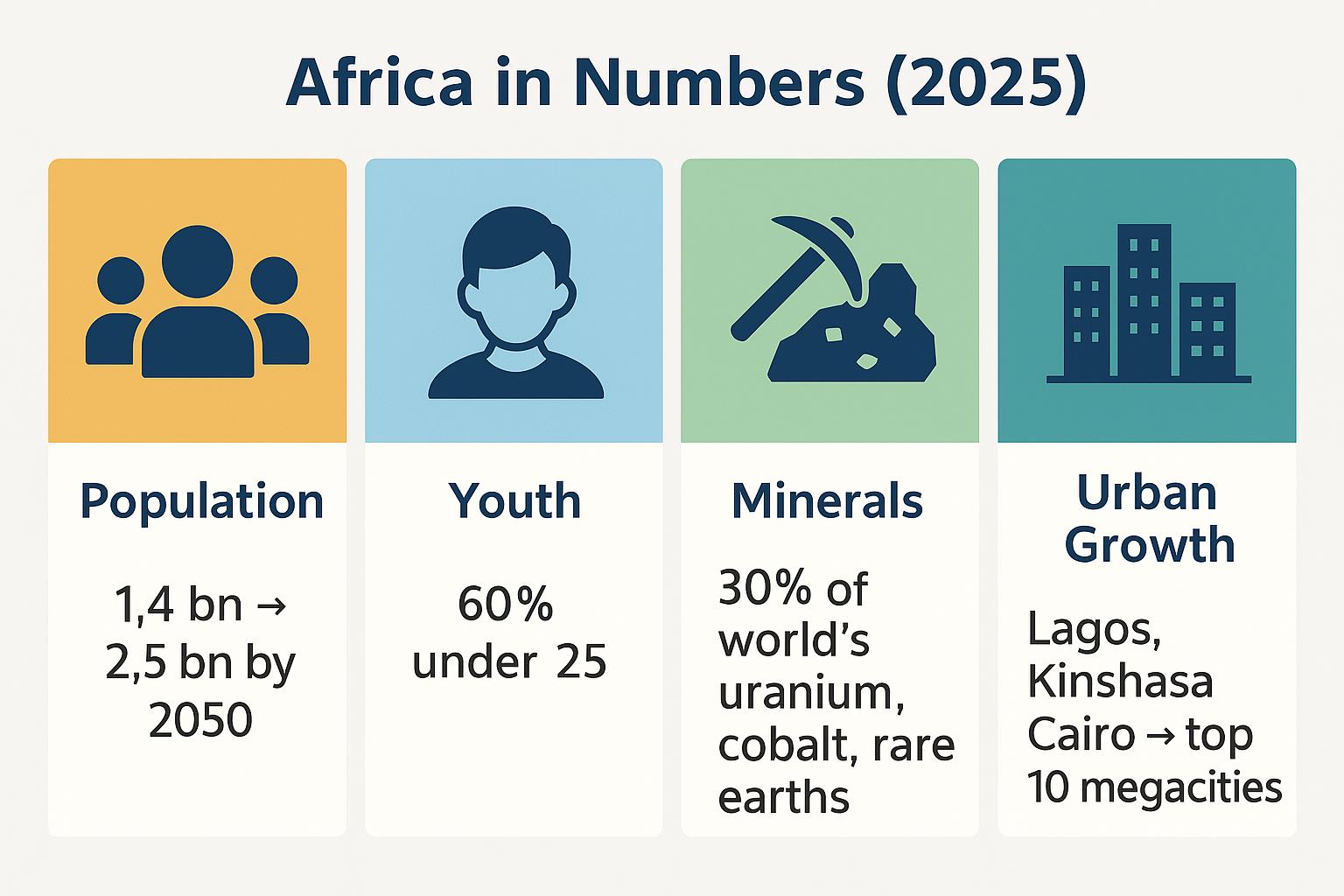

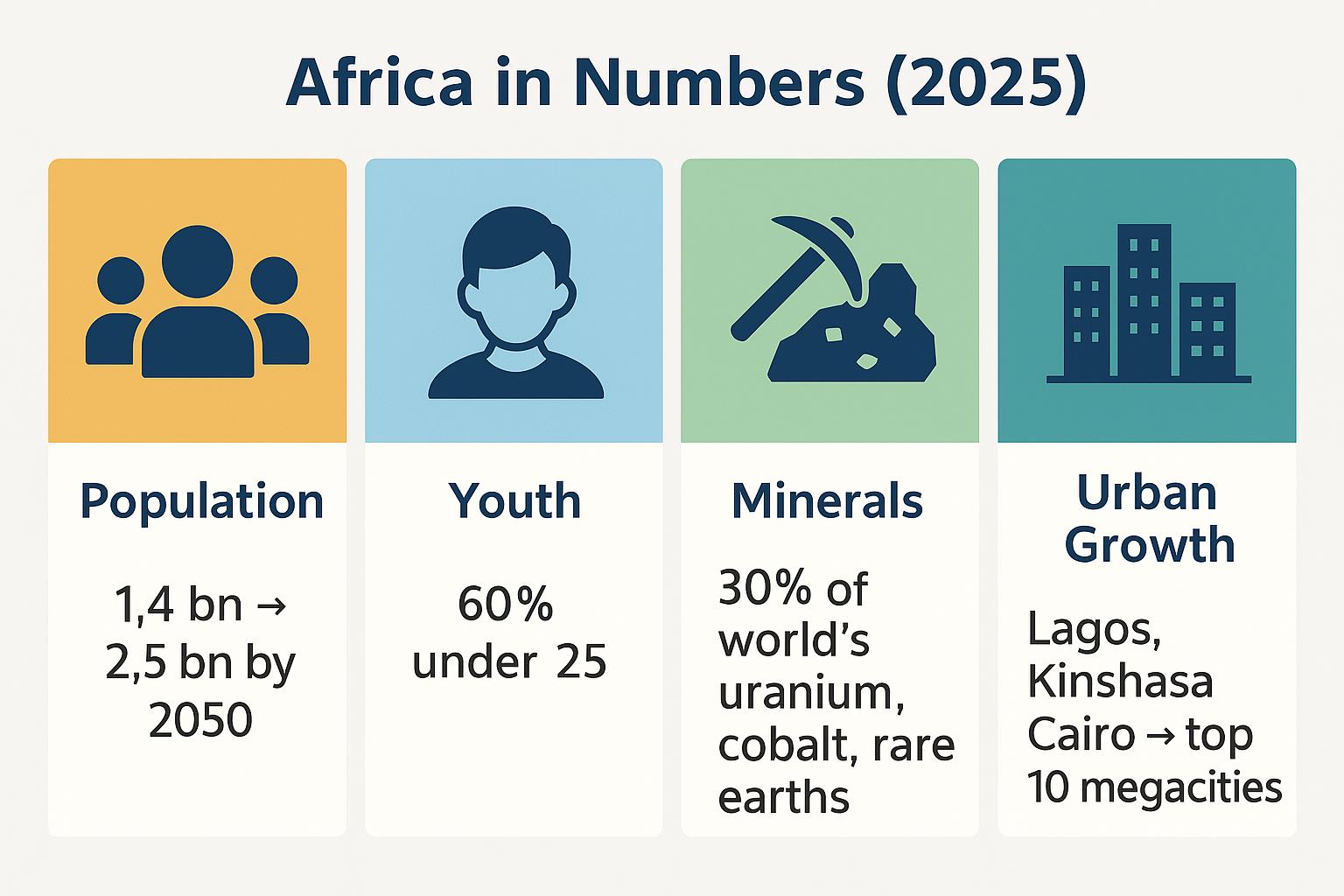

Why It Matters Africa is not a sideshow. It is the world's fastest-growing region, home to vast reserves of uranium, cobalt, and rare earths. Its population will double by 2050, with cities larger than many European states. For Europe, Africa's stability touches directly on migration, terrorism, and energy supply. For China, it is a source of markets and resources; for Russia, a geopolitical battleground; for Turkey and the Gulf, a stage for influence. France's retreat is therefore not just a French story-it is a Western one. It shows how quickly influence can vanish when it rests on paternalism rather than partnership.

Conclusion Has France lost Africa? It has certainly lost its empire-its privileged status as gatekeeper and gendarme. That era is over. But Africa is not France's to lose or win; it belongs to Africans. France can still be relevant if it accepts that reality. If it offers fair trade, real investment, and respect for sovereignty, it may yet remain a valued partner-though never again the dominant one. The alternative is irrelevance, ceding the field to China, Russia, Turkey, and others. At the Élysée this August, as Macron and Faye discussed archives, trains, and trade, one thing was clear: the age of Françafrique is gone. What comes next will depend less on France's nostalgia than on Africa's choices. “Sovereignty does not allow foreign bases.” - Bassirou Diomaye Faye

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Most popular stories

Market Research

- Invromining Expands Multi-Asset Mining Platform, Launches New AI-Driven Infrastructure

- Superconducting Materials Market Size, Trends, Global Industry Overview, Growth And Forecast 2025-2033

- United States Lubricants Market Growth Opportunities & Share Dynamics 20252033

- Building Automation System Market Size, Industry Overview, Latest Insights And Forecast 2025-2033

- Brazil Edtech Market Size, Share, Trends, And Forecast 2025-2033

- Australia Automotive Market Size, Share, Trends, Growth And Opportunity Analysis 2025-2033

Comments

No comment