The Pettis Paradigm And The Second China Shock

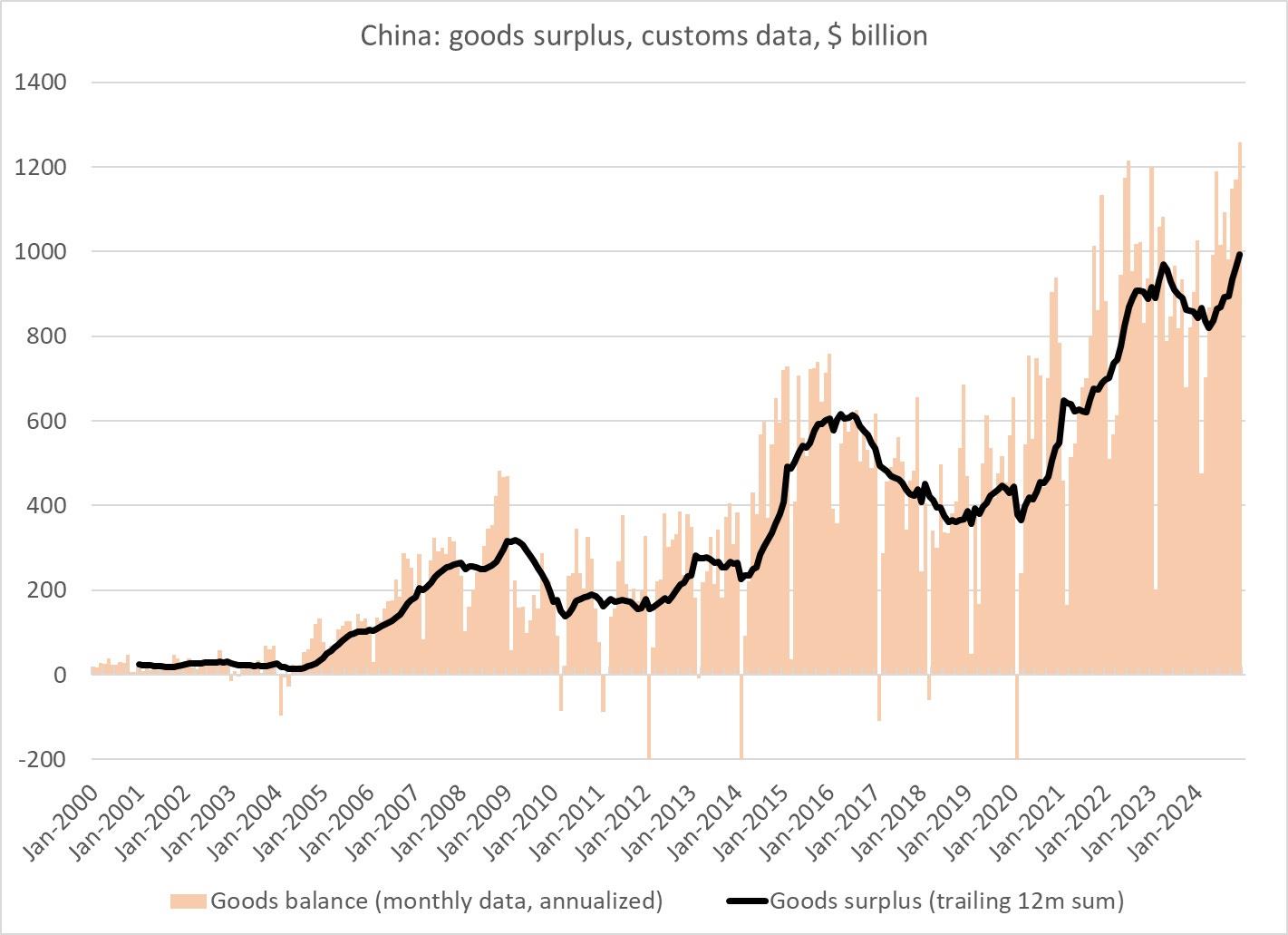

Here's a thread from Setser with a lot more detail on China's surplus. Interestingly, China's exports to the developing world are a lot bigger of a factor here than its exports to the US and the EU, though the latter are up by a little bit.

This is the Second China Shock . Trade surpluses like this can't be explained by the good old theory of comparative advantage - a Chinese trade surplus is just countries writing China IOUs in exchange for physical goods. Countries don't really have a comparative advantage in writing IOUs.(1)

Source:

Brad Setser

Why trade surpluses and deficits do happen is an important and interesting and complex question, and my general impression from reading a bunch of economics papers on the topic is“No one really knows.”

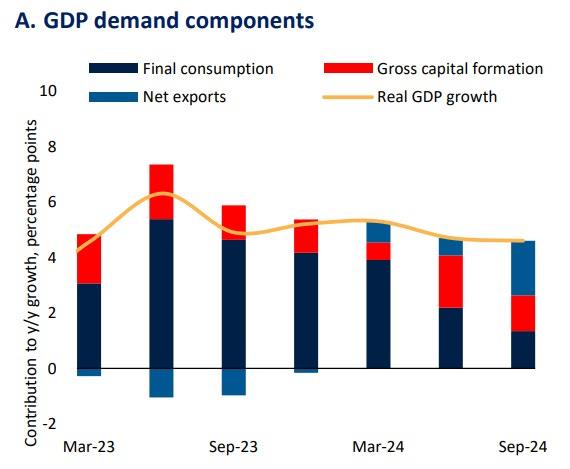

It probably has something to do with the fact that China's government is directing its banks to loan vast amounts of money to manufacturers , and paying manufacturers tons of subsidies on top of that.

But there also has to be some sort of financial factor involved that prevents China's currency from appreciating and allowing Chinese people to buy more imports. This could be something the Chinese government is doing intentionally, or it could be a natural outgrowth of China's economic difficulties . More on this later.

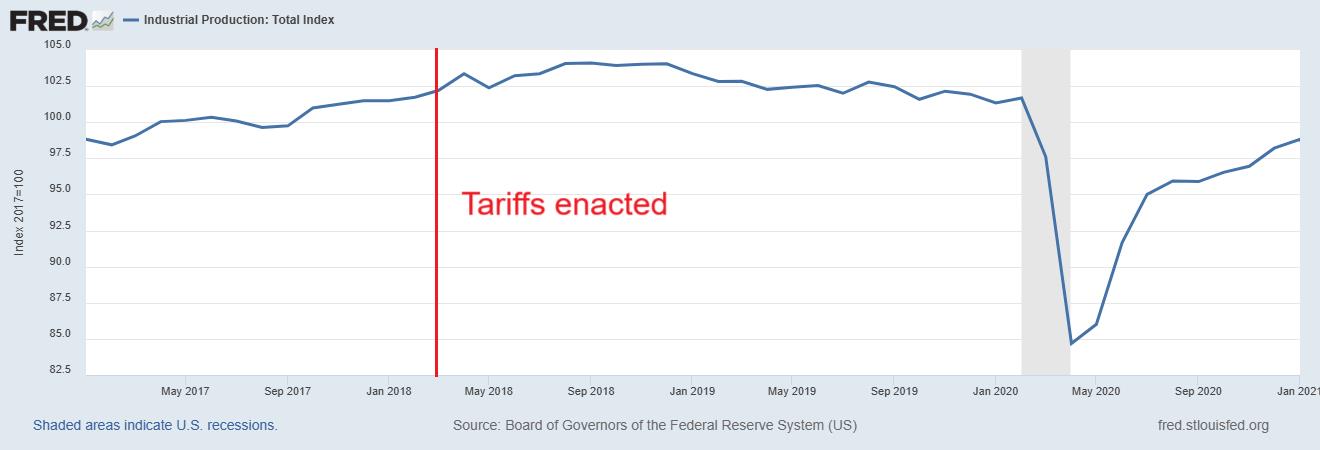

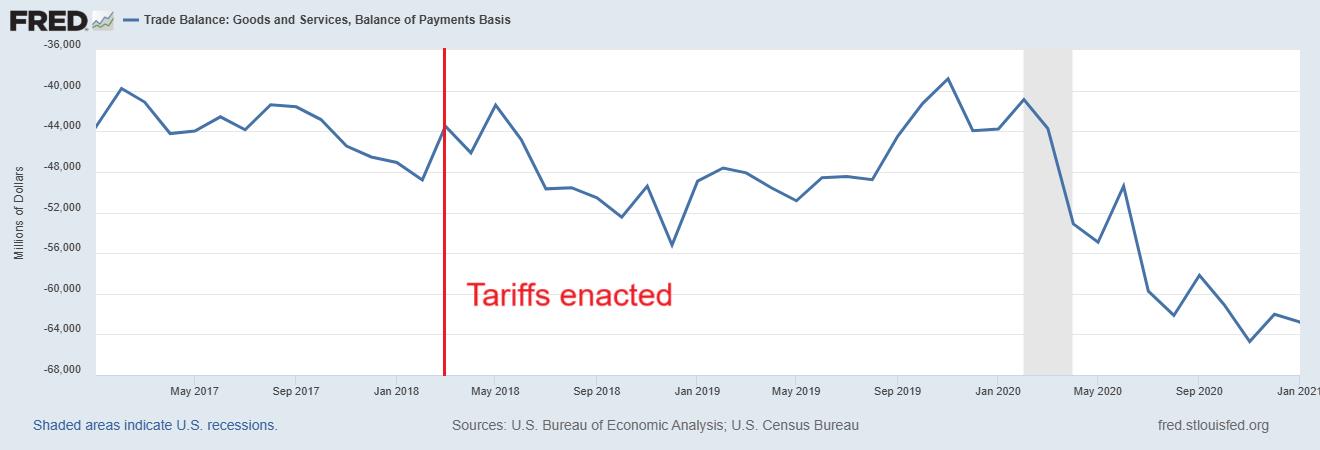

The question is what to do about the vast flood of Chinese exports. Overwhelmingly, from all sides of the commentariat, there has been one main policy proposal (2) for the world outside of China: tariffs on Chinese goods. The MAGA people, obviously, endorse this - tariffs are one of their big policy ideas.

In addition, some commentators suggest that China should shift its economic model toward promoting domestic consumption instead of yet more manufacturing. Many of the people suggesting this are private-sector macroeconomists who work for banks, writers or other private-sector analysts.

But notably, Paul Krugman has said similar things . Many commentators who don't explicitly endorse tariffs will nevertheless say that if China doesn't shift toward consuming more of what it produces, the world inevitably will put tariffs on Chinese goods.

The“other countries should put tariffs on China” idea and the“China should shift its economy toward domestic consumption” idea are unified in the worldview of Michael Pettis , who has advocated both things.

He has been saying that China needs to increase the share of consumption in its domestic economy for well over a decade , and it seems to me that more than anyone, he is responsible for injecting this idea into the discourse. And in an article in Foreign Affairs in December, Pettis laid out a case for tariffs:

Pettis' views on trade policy, and his whole way of thinking about international economics, has drawn pushback from some economists.

For example, in September 2023, Tyler Cowen questioned the focus on Chinese domestic consumption as a target for Chinese growth policy. As an alternative, he suggested that China should focus on improving certain dysfunctional service sectors like health care, which will increase both consumption and production.

In November, Pettis

vented his frustration

with the academic economics establishment in an X thread:

Tyler responded acerbically :

As you know, any time there's an economist food fight, especially over macroeconomics, I am here for it! I wish Tyler had elaborated on his criticisms of Pettis' paradigm, and I also think Pettis is being unfair in his blanket accusations of ideological bias.

But in any case, I think I have four points to make on this topic.

International economics is really, really hardThe first point is that as far as I can tell, nobody really understands international economics. It's basically macroeconomics on steroids. There are a huge number of factors that make issues of tariffs, trade surpluses, and the effect of trade on consumption vs investment very complex. Some of these factors are:

- There are many countries in the world, not just two. Although we tend to think about bilateral trade deficits, in fact third parties matter a lot, and there are a lot of them. For example, if China's trade surplus with America goes down, it might be because China is exporting more components to Vietnam for cheap final assembly, to be shipped onward to American consumers.

- Business cycles matter a lot. If countries are in a depression-style situation where interest rates are at the zero lower bound (a“liquidity trap”), a number of standard results about the effects of trade policies - and results about how monetary and fiscal policy affect trade - go out the window. Right now, there are signs that China is in that situation , but the rest of the world is not.

- Tariffs interact with monetary and fiscal policy . For example, if the U.S. puts tariffs on China, China might try to cancel those tariffs out by printing a bunch of money, which would make the yuan cheaper. These sorts of interaction depend on understanding how monetary and fiscal policy work (which we don't really), and also on understanding how policymakers in countries around the world make decisions about monetary and fiscal policy (which we definitely don't understand).

- Exactly why international trade happens in the first place isn't well understood. There's the classic theory of comparative advantage. There are theories based on capital-intensive countries investing in labor-intensive countries. There's Krugman's“New Trade Theory”, which focuses more on differentiation and variety as the motivation for trade. And so on. The most empirically successful models of trade are just very simple equations called gravity models , which are agnostic on why trade happens, and could arise from a variety of different processes. This means we don't really know the baseline of what trade between the U.S., China, and other countries would look like without Chinese industrial policies or currency market intervention.

- There are all kinds of wrinkles and complications that affect trade, called“ frictions .” These include things like home bias in both consumption and financial investing, sovereign default, currency market frictions, and so on. Economists argue back and forth about which of these frictions cause the various “puzzles” in international trade - disconnects between theory and evidence - or whether that's just how trade works in the first place.

- Competition (also called“market structure”) can throw a wrench into all of this. Trade is carried out by companies, and whether Chinese companies and American companies end up making profits on their exports and their domestic sales will affect how they behave. Domestic competitive environments and international competitive environments both matter, and neither one is particularly well-understood.

In graduate school, I took a class in international finance. The professor who taught that class was known for using advanced mathematical methods borrowed from engineering to make models in which two different frictions interacted to affect international trade. That was a big improvement over the standard theories that could only handle one friction. But what if you have seven? It's hopeless.

I think that one reason no one has come up with an alternative to Michael Pettis' ultra-simple way of analyzing international economics is that anything more complex than that quickly balloons into an absolute nightmare.

Making big sweeping assumptions about how tariffs will affect production and consumption isn't exactly the most rigorous or empirically testable way to think about trade and industrial policy, but if the alternative is a blizzard of unworkable math that probably still makes way too many simplifying assumptions, maybe you just go with the simple thing.

Also, Pettis' paradigm isn't that different from some of the heuristic ideas that orthodox economists have used to analyze trade policy. For example, Ben Bernanke's

early-2000s warnings about a global“savings glut”

bear more than a little similarity to Pettis' ideas, and the IMF's

calls for China to“rebalance” its economy

toward domestic consumption in the mid-2000s are very similar to Pettis' prescription.

Which brings me to my second point: Whatever you think of Pettis' theories, I think he's probably the single most important and influential international economics theorist in the world today.

His framework for understanding China's economy and China's trade policy might not please academics, but from what I can tell, it has been implicitly accepted by most private-sector economists and commentators, and many policymakers as well. It's a poppier version of the old“savings glut” and“rebalancing” ideas, simplified for general consumption.

When I see China's top economic policymakers

use language like this , I'm almost certain they're reading Pettis:

Pettis isn't the only person to talk about China's low level of consumption as a share of GDP as an important problem, or to advocate“rebalancing.” Nor was he necessarily the first. But he has been the most consistent and relentless, and these days I see him cited very frequently . Put simply, Pettis is winning this debate.

A pretty simple way that Pettis could be (sort of) rightMy third point is that I can see a pretty simple way in which an approximation of Pettis' view might be useful, if not to understand international economics in general, then at least to understand the Second China Shock specifically. Basically, it's all about the profits of Chinese companies.

So far, China's main methods of fighting its real-estate-induced recession is to pump up manufacturing production, especially in capital-intensive high-tech industries - machinery, ships, planes, cars, batteries, drones, semiconductors, and so on. The Wire China had

a great interview with Barry Naughton

(probably the top American expert on China's industrial policies) in which he explains what Xi Jinping is trying to do:

In other words, Xi is making the Chinese economy look a little bit more like the old Soviet one, where production was determined by plans instead of by the market. He's using banks and industrial policy to tell Chinese companies to build a bunch of specific high-tech manufactured products, and they're doing what he's telling them to.

Why did this approach fail in the USSR? Ultimately, it was because

Soviet manufacturers were inefficient

- they made a bunch of stuff, but they produced it at a loss. That was unsustainable.

Chinese factories are a lot better than Soviet ones were. But if you tell enough different manufacturers to all produce the same stuff at the same time, they're going to compete with each other, and their profits will mostly fall, and they'll start taking big losses.

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images, videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment