Kim Jong Un's New Line More Bark Than Bite

recent chapter

in

Comparative Connections: A Triannual E-journal of Bilateral Relations in the Indo-Pacific.

Barely a fortnight after the December Workers' Party of Korea Plenum ended, many of the same people were recalled to Pyongyang for the 10th Session of the 14th Supreme People's Assembly (SPA) on January 15. This year's meeting of North Korea's rubber-stamp parliament was grandly titled:“On the Immediate Tasks for the Prosperity and Development of Our Republic and the Promotion of the Wellbeing of Our People.”

As that suggests, like at the plenum the focus was once again on economic policy. Yet, addressing the SPA, Kim began with a warning about the worsening security environment. This included a sideswipe at Seoul:

Kim now acknowledges this other state as a fact – but seems not to accept its right to exist.

Military threats loomed large in Kim's SPA speech. He reiterated the DPRK's longstanding non-recognition of the Northern Limit Line (NLL), the de facto maritime border in the West/Yellow Sea:

“As the southern border of our country has been clearly drawn, the illegal 'northern limit line' and any other boundary can never be tolerated, and if the ROK violates even 0.001mm of our territorial land, air and waters, it will be considered a war provocation.”

Kim then moved on to revising the constitution. He pronounced himself vexed that the ROK constitution lays claim to the whole peninsula, whereas the DPRK's has no such provision. Therefore“it is necessary to take legal steps to legitimately and correctly define the territorial sphere where the sovereignty of the DPRK as an independent socialist nation is exercised.”

If that seems fair, what follows is startling:

Moreover,

Instead, the constitution must specify that

Kim cannot have it both ways. If the ROK is a wholly separate entity, such that“northern half” is a wrong term, then on what conceivable basis can the DPRK lay any kind of claim to it, let alone the right to occupy, subjugate, reclaim, and annex it? He talks as if this were a matter of territory alone – but what of 52 million South Koreans, who (whatever he says) remain compatriots by kinship, language, culture, and history?

Austin to Cambodia opens the way for big defense reset

NATO flirting with war and extinction in Ukraine

No breakthrough, no breakdown at Shangri-La

It will be interesting, to say the least, to see how the amended constitution tries to square all these circles. The existing Supreme People's Assembly will probably be reconvened later this year, to amend the Constitution according to Kim's whims, before a new SPA is elected to approve whatever he comes up with next.

The new line also dictates practical tasks. Kim called for cross-border railways to be cut off, physically, completely, and“irretrievably.” Furthermore,“we should also completely remove the eye-sore 'Monument to the Three Charters for National Reunification' [in] Pyongyang.” The monument

seems

to have come down promptly, with the railway and other work following some months later.

Kim's speech ended in a welter of militancy and contradictions. The DPRK's military buildup does not, he insisted, presage any“preemptive attack for realizing unilateral 'reunification by force of arms.'”

Ah, so this is purely for self-defense?

This second mission reserves the right to make a pre-emptive nuclear strike. In other words, Kim maintains the right to strike first if he feels threatened or provoked.

He concluded:

The pro forma protestation of not wanting to fight seems belied by the glee with which the prospect is savored.

Less than meets the eyeWhat to make of all this? First, this whole turn should be seen primarily as an event in DPRK domestic politics, rather than inter-Korean relations.

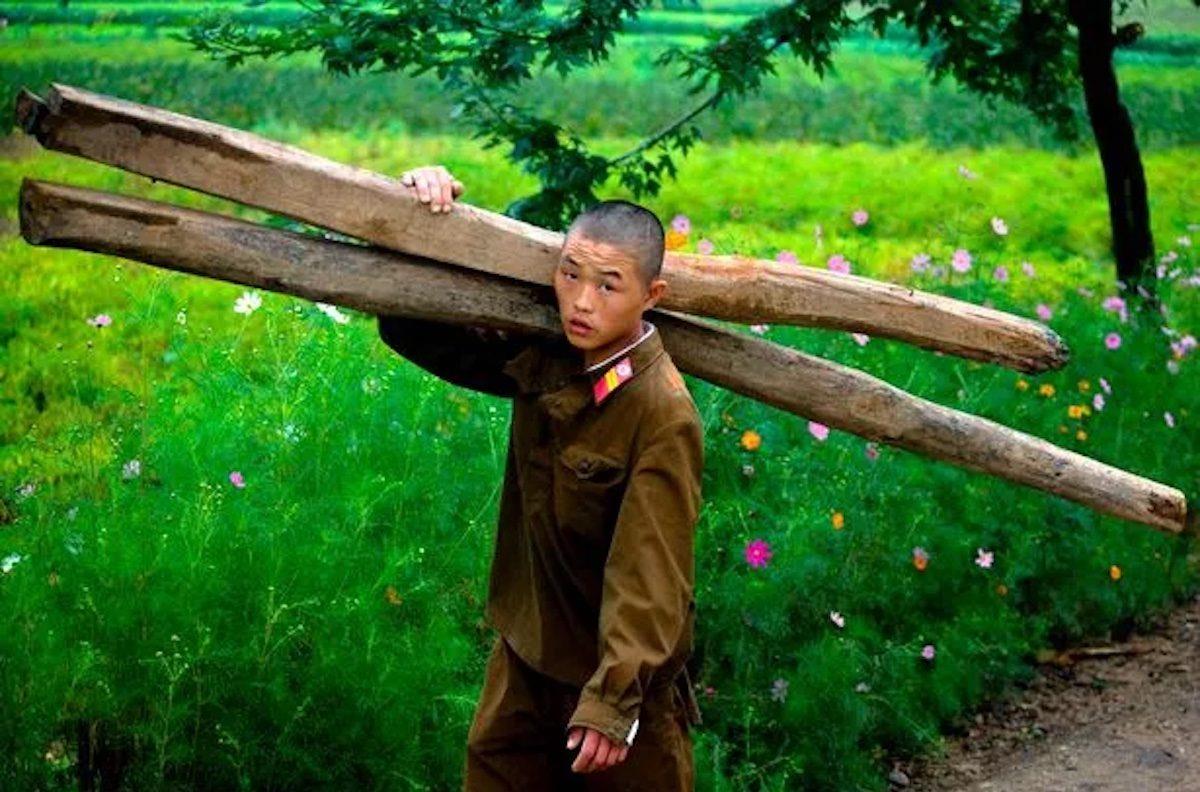

It reflects Kim's frustration, shared by his predecessors, at the fact that South Korea exists: right there, on his doorstep and in his face, ever more successful and infinitely more prosperous. That is a profound challenge on many levels. Any North Korean government must find a way to account for and handle the South, in theory and practice alike.

Second, I suspect this is Kim's own idea. His visceral dislike for the ROK underlay an earlier episode: the razing of Southern-built facilities at the former Mount Kumgang tourist resort.

Kim's remarks at the time betrayed a seething anger at the very idea of South Korean property on Northern territory. He seemed to be against cooperation as such, not just annoyed at how this project had turned out.

Third, another reason to attribute this idea to Kim is the sheer incoherence noted above. What does he mean by“ROK”: Regime? Territory? People? He slips between all three, especially the first two. And if ROK is a separate state, on what basis is the DPRK entitled to subjugate it?

Put another way, this bears the hallmark of Kim Ki Nam's retirement. If the master molder of DPRK ideology and propaganda over many decades had still been on the case – he died aged 94 on May 7, having retired some years earlier – such a crass idea would surely never have been approved. For it solves no problems but creates a number of new ones.

Whatever Kim says, ordinary North Koreans know that South Koreans are in fact their kin, both in general and in particular. Highly publicized family reunions, whatever their inadequacies, are not a distant memory.

People will be puzzled, to say the least, at now being told otherwise. Moreover, this runs directly counter to the line decreed by previous Kims. Kim Jong Un's legitimacy rests largely on fidelity to his father and grandfather, so for him to openly defy this legacy must be risky.

Bark or bite?We know what Kim now says but what will he do? At risk of sounding complacent, my bet is: Nothing much.

First, Kim's keenness to snuggle up to both Russia and China by no means creates a strong, united troika. Behind the formal bonhomie, both Xi and Putin are wary that this Kim might emulate his grandfather and drag them into costly and distracting conflict. China, in particular, which holds the purse strings, will not tolerate peninsular adventurism.

A second point: If Kim seriously intended to cause trouble at the Northern Limit Line, for instance, would he really give advance warning? Hamas did not go around shouting like this before October 7, nor warn that they planned to cut Israel's border fence.

A third reason is Kim's record. Readers may recall the politically tempestuous summer of 2020. Pyongyang frothed with talk of marching south, though this was not billed as a change of line. It all ended explosively, but no one was hurt when the North blew up the (by then unoccupied) former inter-Korean liaison office near Kaesong.

Sign up for one of our free newsletters

- The Daily ReportStart your day right with Asia Times' top stories AT Weekly ReportA weekly roundup of Asia Times' most-read stories

None of this suggests a peninsula on the brink of war. Both sides are pushing the envelope, and the North's new doctrine is alarming if taken at face value – but that is the nub. Kim Jong Un faces a mountain of problems at home. Threatening to subjugate the South solves none of them but may – or may not – briefly distract his people from their hardships.

While vigilance remains essential, Kim's lurid new stance looks very like a new variation on a very old theme of fire-breathing performativity.

Aidan Foster-Carter (... )

is an honorary senior

research fellow in sociology and modern Korea at Leeds.

This article was first published by Pacific Forum and is republished with permission.

Thank you for registering!

An account was already registered with this email. Please check your inbox for an authentication link.

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment