Vast Offshore Network Moved Billions With Help From Major Russian Bank

Vardanyan is a wealthy Russian banker who once led TroikaDialog, the country's largest private investment bank. He's spokenat the World Economic Forum in Davos and spent tens of millions ofdollars on philanthropic projects in his native Armenia. Ustyan isa seasonal construction worker who shares a chilly apartment withhis wife and parents in northern Armenia when he isn't renovatingflats in Moscow.

But Ustyan's signatures on documents he says he's never seen draw adirect line to Troika - and to a financial Laundromat that shuffledbillions of dollars through offshore companies on behalf of thebank's clients, many of whom were members of Russia's elite. Thesystem enabled people to channel money out of Russia, sidesteprestrictions in place at the time, hide their assets abroad, andlaunder money. It also supplied cash to powerful oligarchs, andenabled criminals to mask the illicit origins of their cash.

Ustyan's name and a copy of his passport appear in the bankdocuments for an offshore shell company that played a role inTroika's system. The company was one of at least 75 that formed thecomplex financial web, which functioned from 2006 to early 2013 that period, Troika enabled the flow of US$ 4.6 billion intothe system and directed the flow of $4.8 billion out. Among thecounterparties on these transactions were major Western banks suchas Citigroup Inc., Raiffeisen, and Deutsche Bank. The dozens ofcompanies in the system also generated $8.8 billion of internaltransactions to obscure the origin of the cash.

(Citigroup didn't respond to a request for comment on this story;Raiffeisen declined to comment, citing client confidentiality; andDeutsche Bank said it had“limited access” to information aboutTroika client transactions and couldn't comment on specificbusinesses for legal reasons.)

At the time, Vardanyan was Troika's president, chief executiveofficer, and principal partner. He enjoyed a reputation as aWestern-friendly representative of Russian capitalism, known forworking to improve the country's business environment and forco-founding the Moscow School of Management Skolkovo.

Meanwhile, employees at Troika were setting up the opaque financialsystem - dubbed here the Troika Laundromat because of itsresemblance to previous money laundering schemes uncovered byOCCRP.

As with the previous Laundromats, many of the large transactionswere made on the back of fictitious trade deals. The bogus dealswere invoiced variously as“goods,”“food goods,”“metal goods,”“bills,” and“auto parts.” All the invoices

included in the leak were signed by proxies and sent from Troikaemail addresses.

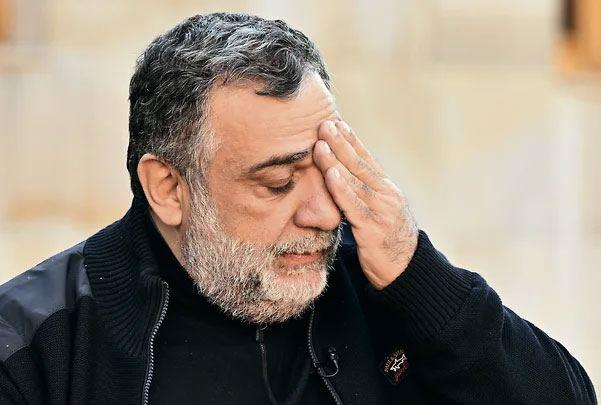

Ruben Vardanyan.

This portrait of the operation emerges from a trove of leakedbanking transactions and other documents obtained by OCCRP and theLithuanian news site 15min, and shared with 21 mediapartners.

As a whole, the data set includes over 1.3 million bankingtransactions from 238,000 companies and people, as well asthousands of emails, contracts, and company registration forms analysis of Troika's network is based on a subset of thedata.

In an interview, Vardanyan said his bank did nothing wrong and thatit acted as other investment banks did at the time. He stressedthat he couldn't have known about every deal his enormous bankfacilitated for its clients. Reporters found no evidence that hewas ever investigated or accused of any wrongdoing by authorities signature was found on only one document(in the entire scheme, in which he gives a loan to a TroikaLaundromat company.

Vardanyan described the system as a private wealth managementservice.

Referring to the constellation of offshore companies that comprisedthe Laundromat, he said:“Those are technical service companies ofTroika Dialog clients, among them, mine.”

“It could be called a 'multi-family office,'” he said.“A similarpractice still exists at foreign banks. Most of their clients workthrough international companies. I repeat: We always actedaccording to the rules of the world financial market of that time ...Obviously, rules change, but measuring a market in the past bytoday's laws is like applying modern compliance standards to thetime of the Great Depression. You'll agree that this distorts thetrue situation.”

Asked about the fictitious trade deals, Vardanyan said TroikaDialog's revenue topped 2 trillion rubles from 2006–2010 ($63–85billion, depending on currency fluctuations) and that he“couldn'tpossibly know about all the deals in a company of this size.”

Though such practices were considered business as usual in Russiaat the time, specialists note that systems like the TroikaLaundromat can have serious repercussions.

The schemes stunt national economic development, undermine humansecurity, and diminish the quality of life for people left behind,said Louise Shelley, director and founder of George MasonUniversity's Terrorism, Transnational Crime, and Corruption Centerand author of the book“Dark Commerce.”

“Money laundering countries, particularly in the developing world,are losing enormous amounts of capital that are needed forinfrastructure development, education, health, [and] thedevelopment of new businesses, of entrepreneurship,” Shelley said.“With this much money lying overseas, you can do all sorts ofmalicious things. You can interfere in electoral processes. You canhelp pay for fake news.”

Criminal Services

The Laundromat wasn't just a money laundering system. It wasalso a hidden investment vehicle, a slush fund, a tax evasionscheme, and much more.

Troika's clients also used it to buy properties in Great Britain,Spain, and Montenegro; to acquire luxury yachts and artwork; to payfor medical services and World Cup tickets; to cover tuition atprestigious Western schools for their children; and even to makedonations to churches.

In addition, the Troika Laundromat enabled organized criminalgroups and fraudsters to launder the proceeds of their crimes and partners have identified several high-level fraudsperpetrated in Russia that used Laundromat companies to hide theorigins of their money.

One of these schemes, known as the Sheremetyevo Airport fuelfraud

(,took place from 2003 to 2008 and artificially inflated aviationfuel prices while depriving the Russian state of more than $40million in tax revenue. The scheme led to a hike in plane ticketprices. More than $27 million was sent by companies involved in thefraud to Troika Laundromat accounts. Vardanyan has not beenimplicated in the scheme and said he had no knowledge of it. In2010, two years after the fraud ended, Troika Dialog beganconsulting for the airport along with Credit Suisse.

A second significant criminal inquiry tied to the Laundromat, fromwhich $17 million ended up in the system, involves a tax avoidancescheme allegedly perpetrated by several Russian insurancecompanies. A man named Sergei

Tikhomirov was accused of concluding false service contracts withthe insurers as a pretext for having them send him large sums ofmoney, which his accusers say he cycled through several accountsbefore depositing it abroad or cashing in. A portion of the moneyended up in the Laundromat. (Tikhomirov did not respond to phonecalls seeking comment.)

In a third case, at least $69 million went to companies associatedwith Sergei Roldugin, a Russian cellist, who became famous afterhis vast unexplained wealth was revealed by OCCRP

(, theInternational Consortium of Investigative Journalists, and othermedia partners in the Panama Papers project. Some of the money thatRoldugin's companies received from the Laundromat originated in amassive Russian tax fraud exposed by Sergei Magnitsky, a Russianlawyer who died in jail after revealing it.

Roldugin didn't respond to an email requesting comment, andVardanyan said that he knew of the cellist, but was not aware thathe had any business dealings with Troika.

Companies involved in the fraud exposed by Magnitsky moved morethan $130 million through the Troika Laundromat. In fact, hundredsof millions of dollars went into and out of the Laundromat forunknown purposes.

Vardanyan said he was not aware of any of these transactions.

“Understand, I'm no angel,” he said.“In Russia, you have threepaths: Be a revolutionary, leave the country, or be a conformist I'm a conformist. But I have my own internal restraints: I neverparticipated in loans-for-shares schemes, I never worked withcriminals, I'm not a member of any political party. That's why,even in the '90s, I went around with no security guards. ... I'mtrying to preserve myself and my principles.”

Vardanyan and his family were among those who received money fromthe Laundromat. More than $3.2 million was

used to pay for his American Express card, went to accountsbelonging to his wife and family, and paid school fees for histhree children in Great Britain.

Asked about these sums, Vardanyan said the offshore companiesTroika created serviced his own companies in addition to the bank'sclients.

Troika as Capstone

The Troika Laundromat is unique among the Laundromats that havebeen uncovered in recent years in that it was created by aprestigious financial institution.

Established in the early 1990s, Troika Dialog became Russia'slargest private investment bank. It operated under Vardanyan'sleadership until 2012, when it was purchased by Sberbank, thenation's largest state-owned lender.

Like all investment banks, Troika handled stock and bond issuance,initial public offerings, and acted as an underwriting agent. Italso had a strong relationship with the local office of CitibankInc., with up to 20 percent of Troika's new investors coming viathe American behemoth. That made New York-based Citibank Troika'sbiggest“external agent,” according to a 2006 interview with Troikaco-founder Pavel Teplukhin. (Citibank didn't respond to requestsfor comment.)

Other major international banks, including Credit Suisse andStandard Bank Group, did significant business with Troika aswell.

Starting in 2006, Troika employees began putting together thepieces of the Troika Laundromat.

Four essential elements are needed to build a functioningLaundromat: a bank with low anti-money laundering compliancestandards; a maze of secretive offshore companies to hold accountsat the bank; proxy directors and shareholders for both thecompanies and the accounts; and the so-called formation agents thatcan quickly create, maintain, and dissolve the offshore companiesas needed.

The bank orchestrated all of these components of the TroikaLaundromat, in addition to directing the money flows and fake tradedeals that made up its operations.

The pivotal mechanism was based on trade: Shell companies createdbogus invoices for non-existent goods and services to be purchasedby other companies in the system. The practice provides a fig leafof legitimate economic activity that makes the transactions appearless suspicious to regulators.

“You're disguising an illegal payment by pretending that it islinked to a shipment of goods,” said Shelley, the George Masoncorruption expert.“The trade-based system is one of the mostcentral parts of money laundering in the world today.”

Al-Qaida founder Osama bin Laden used a similar system to movemoney around the Middle East, she said.

If Troika was the capstone of the Laundromat, its cornerstones werethree British Virgin Islands-based shell companies: BrightwellCapital Inc., Gotland Industrial Inc., and Quantus Division Ltd's first known transaction was on April 12, 2005. Gotlandwas established on Feb. 17, 2006, and Quantus followed six monthslater on Aug. 23.

An analysis of these companies' banking records reveals how theyput the Laundromat together: Starting in 2006, they made numeroussmall payments to a formation agent called IOS Group Inc. to createthe dozens of companies that comprised the complete Laundromat. IOSdidn't respond to requests for comment.

The three cornerstone companies then continued making payments toIOS ranging from 40 to almost 5,000 euros over almost six years tokeep the entire network operating. Over that span, the totalreached over 143,000 euros.

Quantus, for example, paid formation and maintenance fees for theBritish Virgin Islands-based Kentway SA. This company was laterused, among many others, to send millions of dollars to SandalwoodContinental Ltd., a company connected to Sergei Roldugin, thecellist.

Quantus' involvement with Kentway demonstrates the many ways inwhich the Laundromat companies were interconnected. In this case,after first helping establish Kentway, Quantus then funded it withmoney that Kentway forwarded to Roldugin's company.

The Bank

To direct the flow of funds through the Laundromat, Troikaneeded a commercial bank to host accounts for the companiesinvolved. And it needed that bank to avoid looking too closely atthe contracts and trades Laundromat businesses used to justifymoving money from one offshore company to another.

Troika chose Lithuania's Ukio Bankas for the job. (The Lithuanianlender would later be seized by the country's National Bank in 2013for engaging in risky deals and failing to follow regulators'orders.) Ukio is known to have set up accounts for 35 companiesused in the Troika Laundromat, and likely more.

Because Lithuania wasn't yet using the euro, Ukio neededcorrespondent accounts at European banks, such as the AustrianRaiffeisen or the German Commerzbank AG, to handle euro-denominatedtransactions. Those two lenders and many other large European andU.S. financial institutions accepted Laundromat money, though theydid sporadically inquire about the nature of some transactions.

After prodding by one of the correspondent banks, for example, someUkio compliance officers made inquiries about Laundromat paymentsthat didn't make commercial sense.

“What is the essence of this transaction? We have a contract(attached), but to be honest, I don't really get what's happening,”one officer wrote, adding an unhappy face, in relation to a paymentthat went to a company associated with Roldugin.

By this point, the money had already left Ukio's accounts.

Asked why Ukio was chosen as the banker for the offshore companiesTroika created, Vardanyan said it was just one of about 20 banksTroika used around the world.

The Armenian Proxies

A central figure in many of the transactions involving theLaundromat companies was Armen Ustyan. Far from being an investmentbanker, Ustyan, 34, works seasonally as a construction worker inMoscow.

Ustyan's signature can be found on contracts and banking paperworkin the Troika Laundromat along with those of a few other Armenians an old military jacket and hat, he sat down with reportersthis January in his cold living room to answer questions about highfinance.

Ustyan said he had never heard of Dino Capital SA, the Panama-basedLaundromat company whose Ukio bank account was registered using hissignature. A copy of his passport was attached, but Ustyan insistedhe had no idea how it got there.

At his mother's request, he wrote his signature on a piece of paperand concluded that the one associated with Dino Capital hadprobably been forged.

In addition to having his signature associated with Dino Capital'sbank account, Ustyan is also listed as an attorney authorized tosign contracts on the company's behalf, and his signature appearson at least $70 million worth of financial agreements.

The Armenian said he knew none of this, though he did recall a slimconnection to Troika Dialog: While in Moscow looking for work,Ustyan stayed with a Russian Armenian whose brother he said workedfor the investment bank and helped him find employment.

The Moscow address is indeed that of Nerses Vagradyan, a Russiancitizen of Armenian descent. Nerses' brother,

Samvel Vagradyan, is a director of a Russian company that receivedmillions of dollars from Brightwell, a core Laundromat company. ASamvel Vagradyan is also mentioned on Vardanyan's website as adonor to the banker's charitable causes. It's unknown whetherSamvel really worked for Troika.

Neither of the Vagradyan brothers could be reached for comment said he doesn't believe they used his identity.

Another Armenian front man in the Laundromat appears to be EdikYeritsyan. His identity was used to register an account at Ukio forthe Cyprus-based Popat Holdings Ltd. This company was involved inLaundromat transactions worth millions of dollars.

Yeritsyan told OCCRP that he lost his memory three years ago aftera car accident and doesn't remember some parts of his life, Ustyan said that he and Yeritsyan lived together in a sameflat they were renovating in Moscow.

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images, videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Most popular stories

Market Research

- Manuka Honey Market Report 2024, Industry Growth, Size, Share, Top Compan...

- Modular Kitchen Market 2024, Industry Growth, Share, Size, Key Players An...

- Acrylamide Production Cost Analysis Report: A Comprehensive Assessment Of...

- Fish Sauce Market 2024, Industry Trends, Growth, Demand And Analysis Repo...

- Australia Foreign Exchange Market Size, Growth, Industry Demand And Forec...

- Cold Pressed Oil Market Trends 2024, Leading Companies Share, Size And Fo...

- Pasta Sauce Market 2024, Industry Growth, Share, Size, Key Players Analys...

Comments

No comment