Unusual Tonga Volcanic Eruption That Had The Potential To Warm The Planet

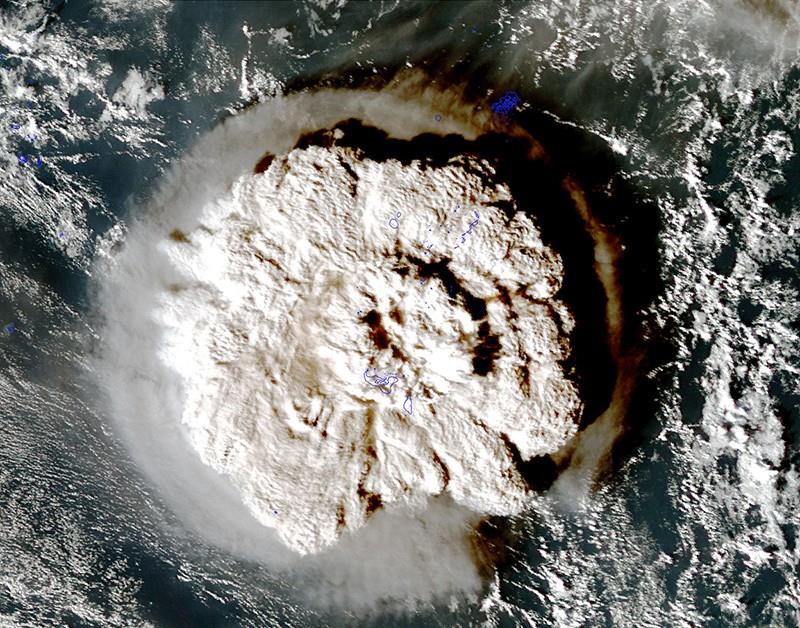

In January, an undersea volcano in Tonga erupted, producing a large and unexpected watery blast that scientists are still attempting to comprehend fully.

Tonga VolcanoHunga Tonga-Hunga Haapai is a submarine volcano in the South Pacific that is situated about 65 kilometers (40 miles) north of Tongatapu, the main island of Tonga, and about 30 kilometers (19 miles) south of the undersea volcano Fonuafoou. The sinking of the Pacific Plate beneath the Indo-Australian Plate created the extremely active Kermadec-Tonga subduction zone and its associated volcanic arc, which stretches from New Zealand to Fiji in the north-northeast. It is located approximately 100 kilometers above a seismically active area.

The volcano rises around 2,000 meters above the ocean's surface, and it contains a caldera that, on the eve of the eruption in 2022, was about 150 meters below sea level and 4 kilometers wide at its widest point.

The twin uninhabited islands of and Hunga Haapai, respectively a part of the northern and western rims of the caldera, are the only significant above-water portion of the volcano. Due to the volcano's history of eruptions, the islands were one landmass from 2015 to 2022. In 2014–2015, a VEI 2 volcanic eruption caused a volcanic cone to join the islands, and in 2022, a more powerful eruption again divided the islands while also shrinking their size.

Its most recent eruption in January 2022 resulted in a volcanic plume that traveled 58 km (36 mi) into the mesosphere and a tsunami that stretched as far as the shores of Japan and the Americas. The eruption is the most significant volcanic eruption date in the twenty-first century as of May 2022. There was probably a last-sized explosive eruption on Hunga Tonga-Hunga Haapai in the late 11th or early 12th century (possibly in 1108). There have been several known eruptions in 1912, 1937, 1988, 2009, 2014–15, and 2021–22.

According to a study published on Thursday in Science, the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai volcano ejected millions of tons of water vapor into the atmosphere.

The second layer of the atmosphere, above the range where people live and breathe, is called the stratosphere. According to the researchers, the eruption increased the amount of water in the stratosphere by about 5%.

Currently, researchers are attempting to determine how all that water might impact the atmosphere and whether it might cause Earth's surface to warm in the coming years.

Lead author Holger Voemel, a scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Colorado, said,“This was a once-in-a-lifetime event.”

The planet frequently cools after significant eruptions. According to Matthew Toohey, a climate researcher at the University of Saskatchewan who was not involved in the study, most volcanoes emit significant amounts of Sulphur, which disperses clouds and blocks the sun's rays.

The Tongan explosion had far more water than typical because it originated under the ocean. Furthermore, the eruption will likely increase temperatures rather than decrease them because water vapor functions as a heat-trapping greenhouse gas, according to Toohey.

It's unknown how much warmth we might experience.

The effects should be slight and transient, according to Karen Rosenlof, a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration climate scientist who was not involved in the study.

Rosenlof wrote in an email that“this amount of increase might warm the surface a little bit for a short amount of time.”

According to Toohey, the water vapor will remain in the upper atmosphere for several years before entering the lower atmosphere. Rosenlof stated that the additional water might also hasten the ozone hole in the atmosphere.

But since they have never witnessed an explosion like this, scientists cannot declare with certainty.

According to Voemel, the stratosphere is often quite dry and ranges from 7.5 miles to 31 miles (12 km to 50 km) above Earth.

With a network of devices strung from weather balloons, Voemel's team calculated the volcano's plume. According to Voemel, the amounts of water in the stratosphere are typically so little that these instruments can't even measure them.

ResearchAnother research team used a NASA satellite's equipment to track the explosion. They predicted the eruption would be even more powerful and produce three times as much water vapor in the stratosphere as Voemel's study revealed earlier this summer published study.

Voemel agreed that because the balloon instruments may have missed some of the plumes, the satellite imaging may have seen more of it, raising its estimate.

He claimed the Tongan explosion was unlike anything witnessed recently, and research into its aftereffects could provide novel information about our environment.

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment