Weighing Why China Is Juicing Exports

very large tariffs

on a number of Chinese-made goods. Those tariffs appear to have acted as a catalyst for a bunch of other countries - India, Brazil, Vietnam, Thailand, Mexico, the EU, etc. - to

consider their own tariffs

on China.

In other words, much of the world now sees the Second China Shock as a danger to their own manufacturing industries and is acting accordingly.

This is a huge, momentous shift. A year and a half ago, when

I declared

that the global economic system that had defined the previous 2-3 decades was now breaking down, some people naturally thought I had overstated my case. Now even critics of the shift are forced to admit that

a new era is upon us .

What the era of decoupling, competition, and fragmentation means for the world, and how to manage it effectively, will be the subject of a huge amount of discussion and analysis in the years to come. But for right now, an interesting question that I think deserves more thought is: Why is China exporting so much stuff?

Most of the new trade barriers and industrial policies that we see popping up all over the world are either directly or indirectly China-related. The new tariffs are explicitly in response to China's vast and rising trade surplus in manufactured goods:

Source: CFR

There are a number of theories floating around out there about why Chinese cars, chips, steel, solar panels, machinery, and other goods are flooding world markets. The theories aren't generally mutually exclusive - it could be some combination of any or all of these. But I thought it would be useful to gather all the hypotheses in one list.

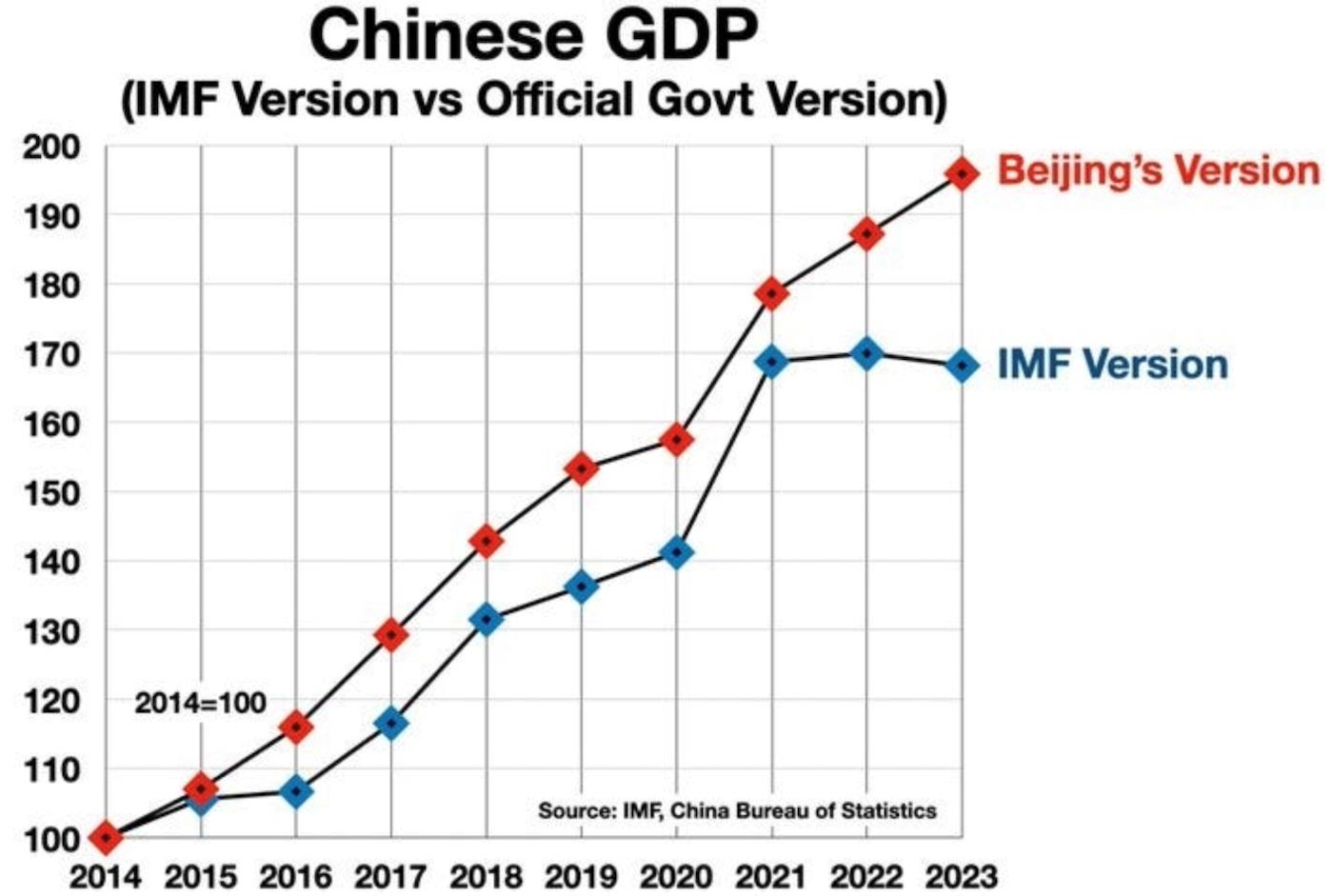

Theory 1: Economic stimulusIn the 2000s, Chinese exports soared even as the Chinese economy was also powering ahead with rapid growth. The two went hand in hand. The 2020s are different; China's exports are booming even as the economy is slowing down. Official statistics say that the country is still growing at a fairly healthy rate of around 5%; independent estimates put the number

closer to 1.5% , or

even 0% :

Screenshot

The reason for this slowdown is

a gigantic real estate bust . Real estate and related industries like construction and finance had come to dominate China's economy, serving as a combination of local government finance, jobs program, and personal savings vehicle. In 2021 the industry started to experience a sharp downturn that is

by no means over .

The slowdown has destroyed a vast amount of paper household wealth and created a massive buildup of largely hidden bad debts within the banking system. This threatens to cause a rise in joblessness. In the past, China's government responded to economic shocks by pumping up real estate, but that isn't working now.

So instead, it makes sense to stimulate some other part of the economy. And since Xi Jinping doesn't seem to believe that consumption and service industries make a country strong, the natural alternative for keeping young Chinese people employed is just to manufacture a whole bunch of stuff.

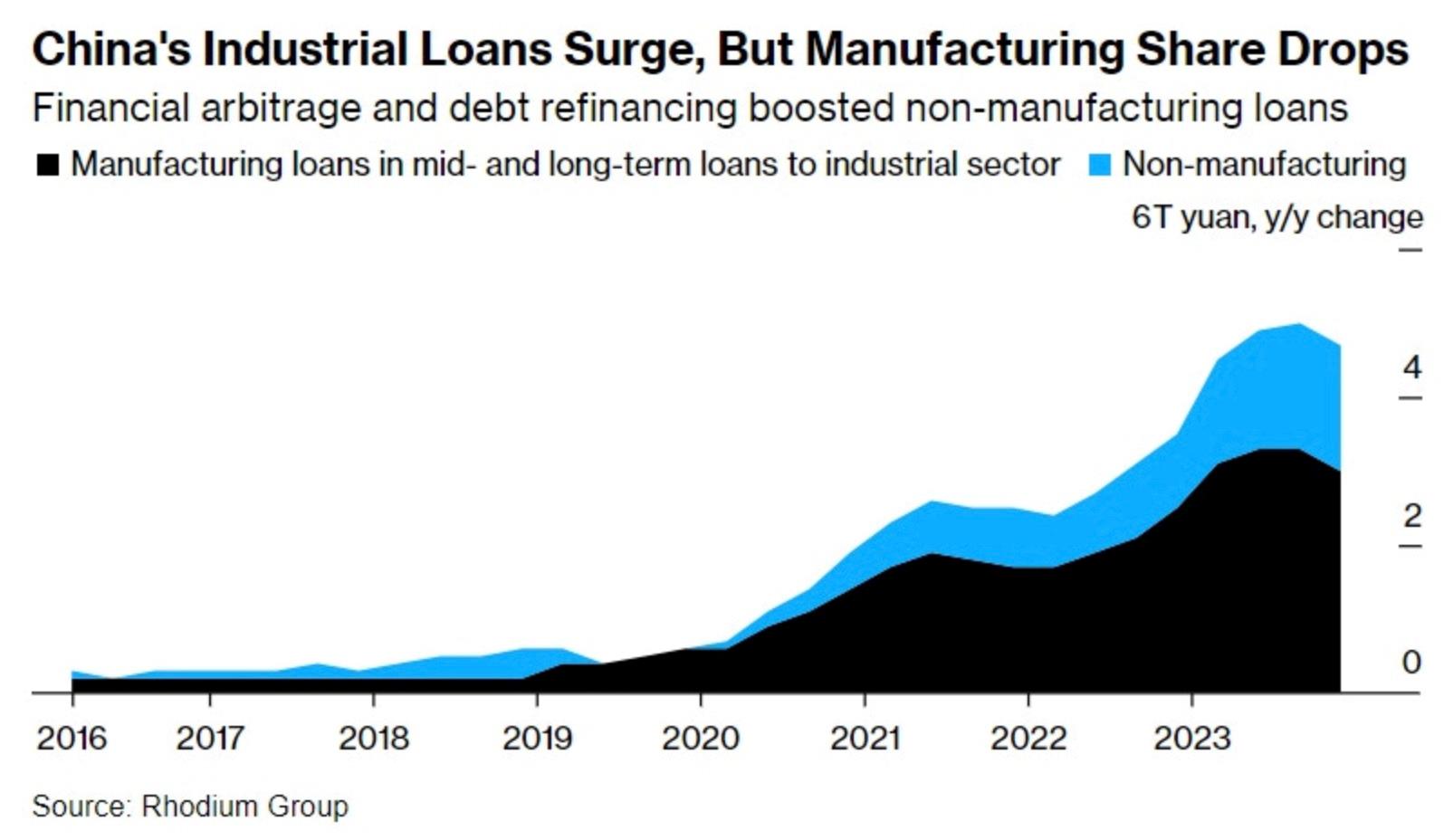

Since real estate began to crash, there has been a huge surge in industrial lending in China. Some portion of this has been used as a stealth bailout for distressed sectors, but a lot of it has gone to manufacturing:

Even if this expansion isn't purely efficient from a supply-side or productivity perspective, it might be worth it from a demand-side perspective - i.e., keeping Chinese people working so they don't get mad at the government.

So this is the first theory: Industrial expansion as a replacement for the real estate boom.

Theory 2: Overcapacity/underconsumptionThere's a second, closely related theory that generally goes by the name of“overcapacity.” In a nutshell, the idea is that China's consumption has slowed down as a result of the real estate bust, but due to government subsidies and other factors, production hasn't slowed.

Thus, Chinese producers who are being paid to make stuff but who can no longer sell it locally are just going to dump1 their product on the world market and hope somebody buys it. Overcapacity is what National Economic Council Director Lael Brainard cited as the main reason for the new tariffs in a recent speech :

It's very difficult to tell whether this is actually happening. The Rhodium Group has a report called“Overcapacity at the Gate”, in which they show that capacity utilization at Chinese factories in subsidized industries has fallen by a lot. That suggests that Chinese companies have built a bunch of factories they're not using - pretty typical for a country in a recession.

But if they're not using the factories, they can't be using them to fill export orders either - at least, not yet. So there's still the question of why they would start using the spare factory capacity instead of just shutting it down.

One possible answer is“subsidies.” Yoko Kubota and Clarence Leong had a great article in the WSJ about a Chinese auto company that should have gone bust, but was saved by government support:

This isn't unusual for China.

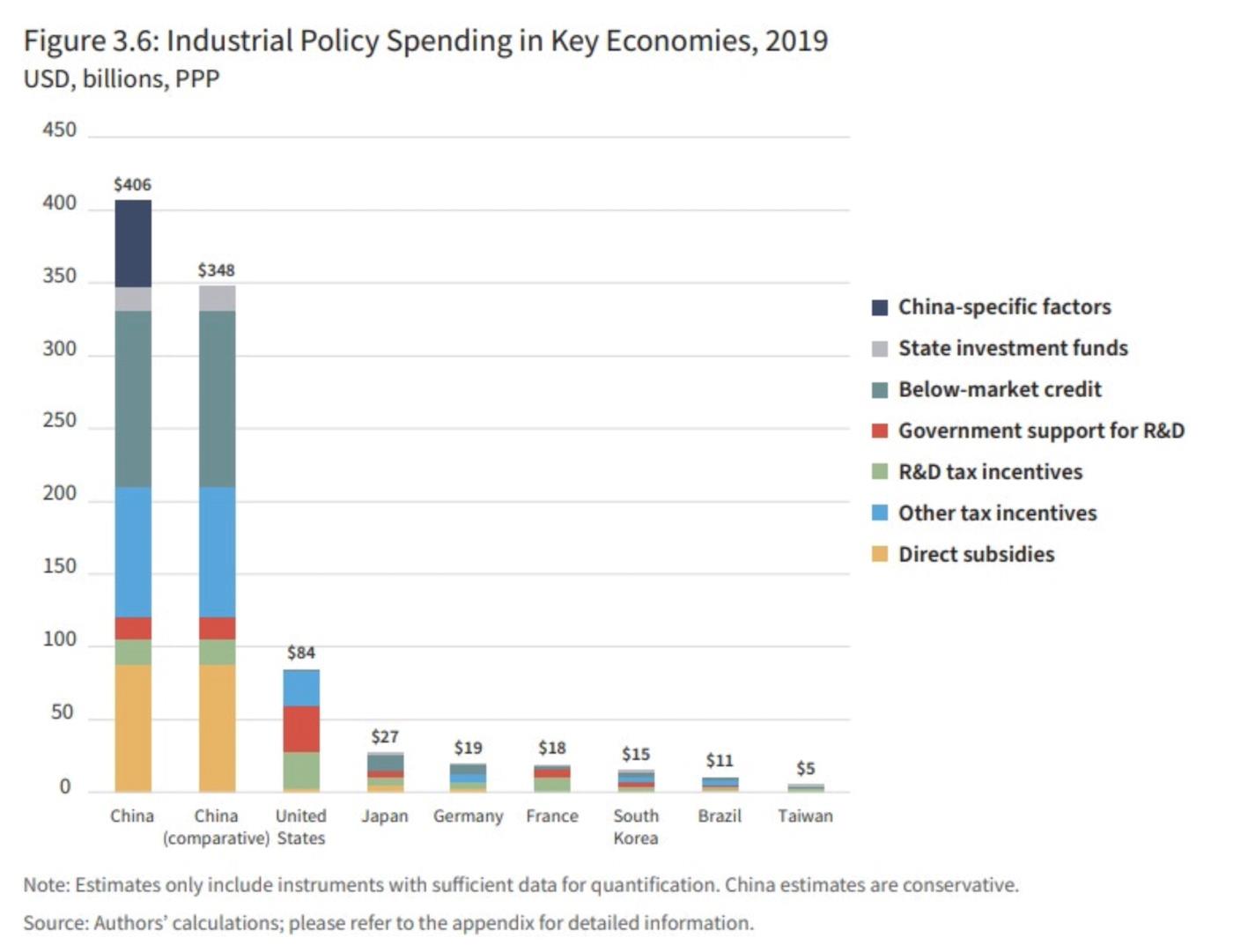

A CSIS report in 2022

tried to measure China's total support to manufacturing companies, and the numbers they arrived at were eye-poppingly huge:

Source: CSIS

So a lot of overcapacity may be driven by these subsidies.

But there's actually a second possible reason for overcapacity, which is much more benign from a policy perspective. A country with a very large domestic market may experience swings in consumption that are so rapid that producers have trouble adjusting their production plans to meet the changes in demand.

This can result in swings in imports and exports that look huge from an international perspective but are actually small compared to the domestic market.

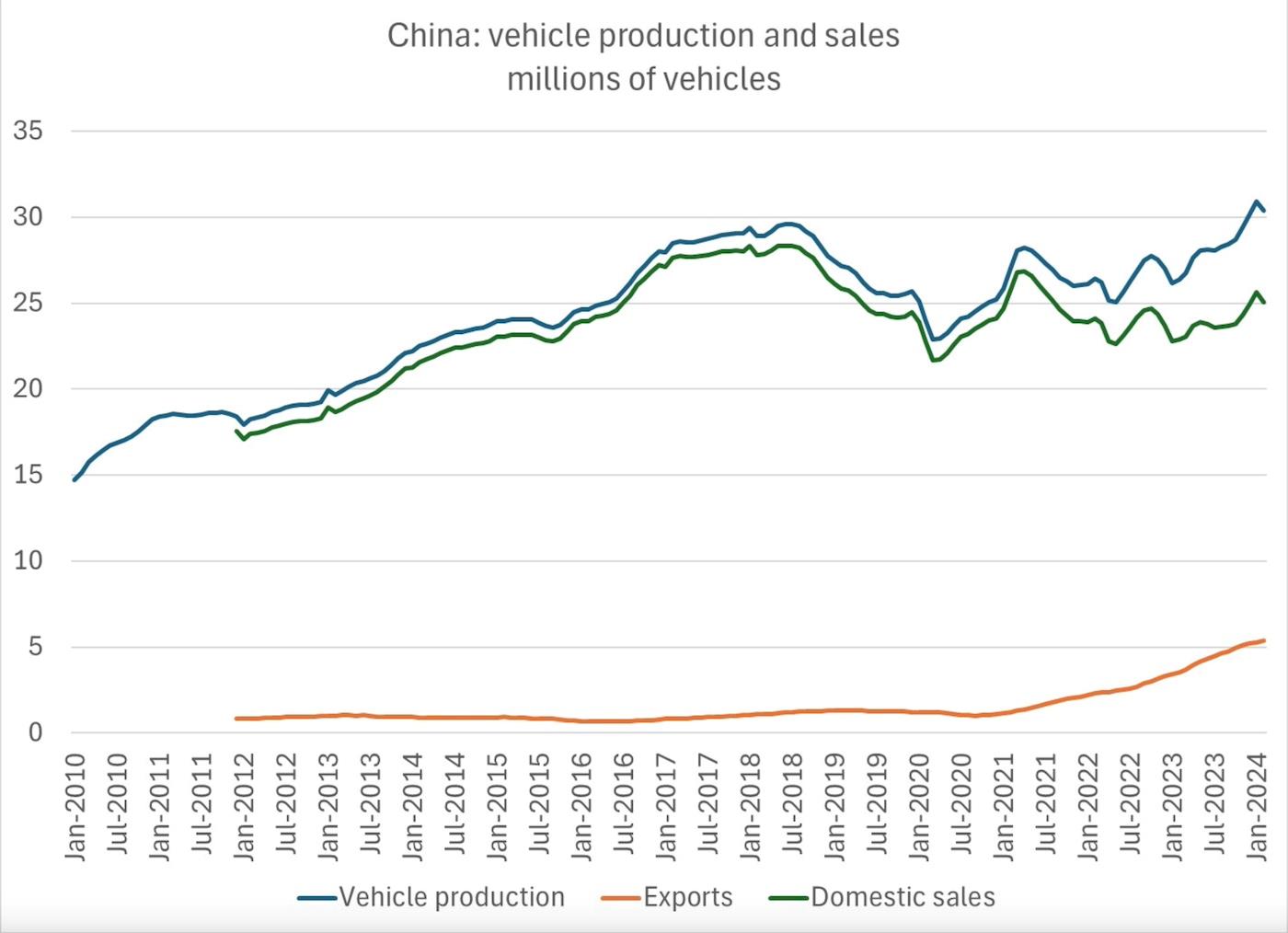

For example, Chinese domestic vehicle sales have decreased recently, probably as a result of the slowing economy. That slowdown, coupled with roughly flat production, has resulted in a gigantic percentage increase in auto exports, even though those exports are still only one-sixth of domestic consumption:

Source: Brad Setser

Similar patterns manifest in

steel

and some other industries.

Why India wants another aircraft carrier

China 'foremost perp' of foreign influence in Canada

Russia and China BFFFF – for the foreseeable future

In fact, China

exports far

fewer

cars

as a percent of total production than countries like Japan or Germany. But because China is just so huge, what look like small swings to China are huge, disruptive swings for other countries around the world.

In the short term, it's very hard to tell whether overcapacity is being driven by subsidies or by companies simply not being able to adjust quickly to drops in domestic demand. The Rhodium Group calls these “structural” versus“temporary” overcapacity.

But both versions manifest as a seemingly huge flood of cheap Chinese goods glutting world markets and threatening other countries' manufacturing industries.

Theory 3: Comparative advantageChina's leaders, of course, strongly contest the idea that their country is suffering from overcapacity. In a speech on April 30 , Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Lin Jian argued that China's exports simply represent the country taking its natural place as the world's manufacturer:

Lin is slightly misapplying the theory of comparative advantage here. Comparative advantage explains balanced trade - I give you soybeans because I'm good at growing soybeans, you give me cars in exchange for soybeans because you're good at making cars, and so on. It can't explain unbalanced trade - you give me cars in exchange for IOUs. Trade surpluses and deficits require ideas that go beyond comparative advantage.

But Lin's core belief here is that manufacturing is simply what China does best and that fundamental economic factors dictate that China should do more of it, and other countries should do correspondingly less. Perhaps in the end, trade will balance out, and other countries will deindustrialize and become farms, financial service providers, and so on, while China makes all their goods.

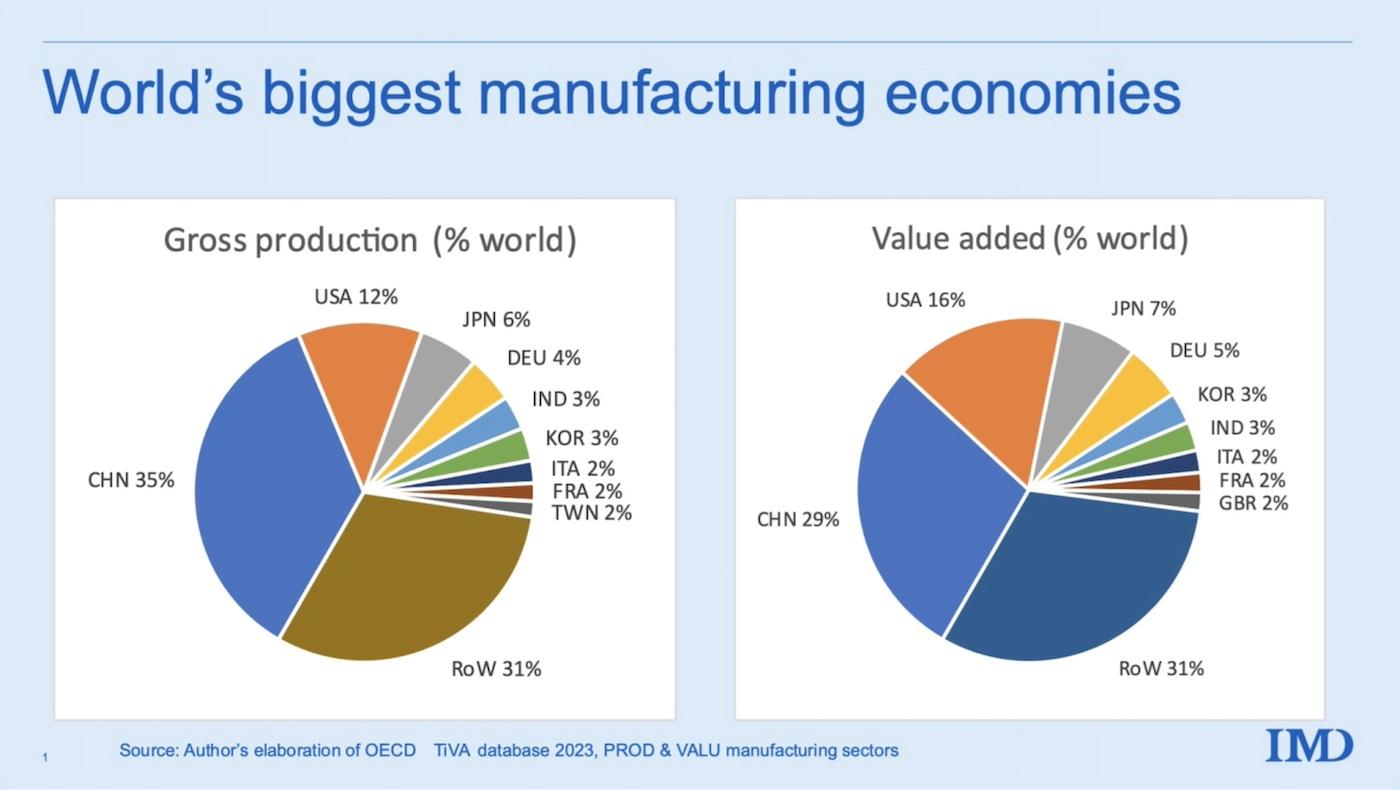

This isn't

such

a far-fetched notion. In the 20th century, Europe, the US, and a few countries in East Asia made most of the world's manufactured goods, so it's possible for manufacturing to be very geographically concentrated. And China has an enormous fundamental strength that no other country has (except perhaps a future India) - its vast internal market.

China has a vast number of consumers, who will tend to prefer Chinese products (out of cultural proximity, even without taking nationalism into account). That huge domestic market allows Chinese manufacturers to reach enormous scale, driving their costs down relative to companies in other countries, even before they export anything.

It also allows China to have a vast network of suppliers for every type of manufacturing, without having to order many parts and materials abroad. And it tends to create clustering effects, where all the EV makers or chipmakers want to go to China because that's where the greatest numbers of their competitors are located; companies like to poach employees and appropriate ideas from their competitors.

So it's possible that China's massive flood of exports is

simply a transitory stage

in a long-term shift of global manufacturing to its natural location. Chinese economic planners

may believe

that accelerating this inevitable shift is the best way to boost their country's growth:

“China wants to be the Amazon of countries - Amazon is the everything store, China wants to be the 'make everything' country,” said Damien Ma of US think tank Macropolo, who met senior policymakers in Beijing last year.“The vision is to bring a complete supply chain to China.”

There are some issues with this theory, of course. Why would an inevitable transition need such massive subsidies? Why would comparative advantage manifest as many decades of unbalanced trade? But basically, I think something like this theory is what many Chinese policymakers either believe - or will profess to believe, in order to defend China from accusations of“overcapacity.”

Theory 4: Forced deindustrializationThere is another, darker version of the“comparative advantage” theory. This is the notion that China is intentionally trying to wreck the manufacturing industries of its geopolitical rivals, in order to gain a military advantage over them.

In any major protracted war, industrial capacity becomes extremely important. Civilian manufacturing gets repurposed for military use. The most famous example is when the US

out-manufactured its opponents

in World War 2. The US still has a law called the Defense Production Act that's supposed to allow a repeat of the civilian-to-military factory conversion.

The larger the percentage of global manufacturing China has, and the lower the percentage its rivals have, the better its chances would be of overwhelming those rivals in a war.

Gaining a commanding share of global manufacturing might even allow China to displace the US and its allies as the world's dominant power - something the country's leaders have

repeatedly said they want to do

- without a fight. Currently, the blocs are about evenly matched:

Source: CEPR

The Second China Shock might tip that balance decisively in China's favor.

Comparative advantage, on its own, probably won't be enough to make that happen. Usually, when new countries added themselves to the roster of high-output, high-tech manufacturers, they didn't cause wholesale deindustrialization in other countries. The First China Shock coincided with a big decrease in US

manufacturing employment , but actual manufacturing output remained

about the same .

That's where subsidies could come in. If Chinese government subsidies make it essentially impossible for any non-Chinese company to compete, it could artificially tip the balance of comparative advantage, to the point where the US, Europe, Japan, and Korea could be inefficiently bereft of manufacturing industries - at least as long as China keeps up the subsidies.

That window of time might be enough for China to accomplish its military objectives (e.g. conquering Taiwan), and establishing itself as the global hegemon.

An outcome like this is something the US and others would naturally want to prevent, and my bet is that the threat of forced deindustrialization was very much on the minds of the people who crafted the new tariffs.

Theory 5: Xi Jinping's techno-historical theoriesOne possibility that we can never dismiss is that China does things simply because it has an absolute ruler who decides to do those things. Tanner Greer, director of the Center for Strategic Translation, believes that Xi Jinping and his hand-picked subordinates are obsessed with propelling China to greatness by monopolizing a few high-tech industries of the future:

This might sound like a bunch of Marxist mumbo-jumbo, but it's actually not very different from how other countries think about technology, industry, and the national interest.

For example, if you read

the White House's report

on“critical and emerging technologies”, the language is a little less millenarian, but the basic idea is recognizably the same - if you want your country to be powerful, it's good to monopolize strategic cutting-edge high-tech industries as much as you can.

As to what those key technologies are, neither the Chinese government nor the US government appears to be quite sure - instead they're placing diversified bets across a number of industries, in case any of those turn out to be the key to the future. Greer writes:

That's an incredibly general list. But maybe Xi and the Politburo think China needs to massively subsidize all of these things in order to maximize its chances of being a superpower in the world of tomorrow. The export boom could be downstream of that decision.

Theory 6: War preparationThere is one last theory that is the darkest of all, which I only hear muttered in hawkish national security circles. This is the idea that China's subsidy-driven manufacturing boom represents the beginning of war production.

There are basically two parts to this theory. First, as I mentioned, countries at war convert civilian production lines to military production. So building up civilian industries like steel and computer chips that are easily converted to military use could be a way of preparing for this conversion. Nathaniel Sher, writing in The National Interest, hypothesizes something along these lines :

Second, any country at war is vulnerable to having its supply lines cut, so building up domestic manufacturing of critical components like chips is a way to insulate a country against sanctions and blockades. Under Xi Jinping, a big focus of Chinese industrial policy has been to onshore entire supply chains, and the current big manufacturing push is continuing that trend :

This strategic shift is not just related to trade wars, perceived supply chain vulnerabilities, or de-risking dynamics. Xi seems to have studied the sanctions playbook the West used against Russia over Ukraine and subsequently initiated long-lead protective measures to batten down the hatches of China's economy to resist similar pressure.

This is the most ominous theory of all. It suggests that the export boom might be incidental - an accidental side effect of China's creation of the greatest military production machine the world has ever known.

So which theory is right?It's important to reiterate that none of these theories are mutually exclusive. It's possible that the objectives of war production, industrial policy, forced deindustrialization of rivals, and recession-fighting simply align in the minds of China's leaders.

And it's possible that natural forces like China's recession and a long-term shift of manufacturing to China are lending a helping hand to the government's effort.

All of these theories could be true at once.

Or perhaps only some subset of them.

But I think breaking the possibilities down in this way is a helpful prelude to thinking carefully about what tariffs and other protectionist measures might realistically hope to accomplish.

This article was first published on Noah Smith's Noahpinion Substack and is republished with kind permission. Read the original and become a Noahopinion subscriber here.

Thank you for registering!

An account was already registered with this email. Please check your inbox for an authentication link.

Sign up for one of our free newsletters

- The Daily ReportStart your day right with Asia Times' top stories AT Weekly ReportA weekly roundup of Asia Times' most-read stories

Legal Disclaimer:

MENAFN provides the

information “as is” without warranty of any kind. We do not accept

any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images,

videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information

contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright

issues related to this article, kindly contact the provider above.

Comments

No comment