(MENAFN- Asia Times) China has decided to fight widespread anti-Covid lockdown protests by combining the heavy dose of official repression of the past week with a sudden willingness to relieve tight restrictions on movement.

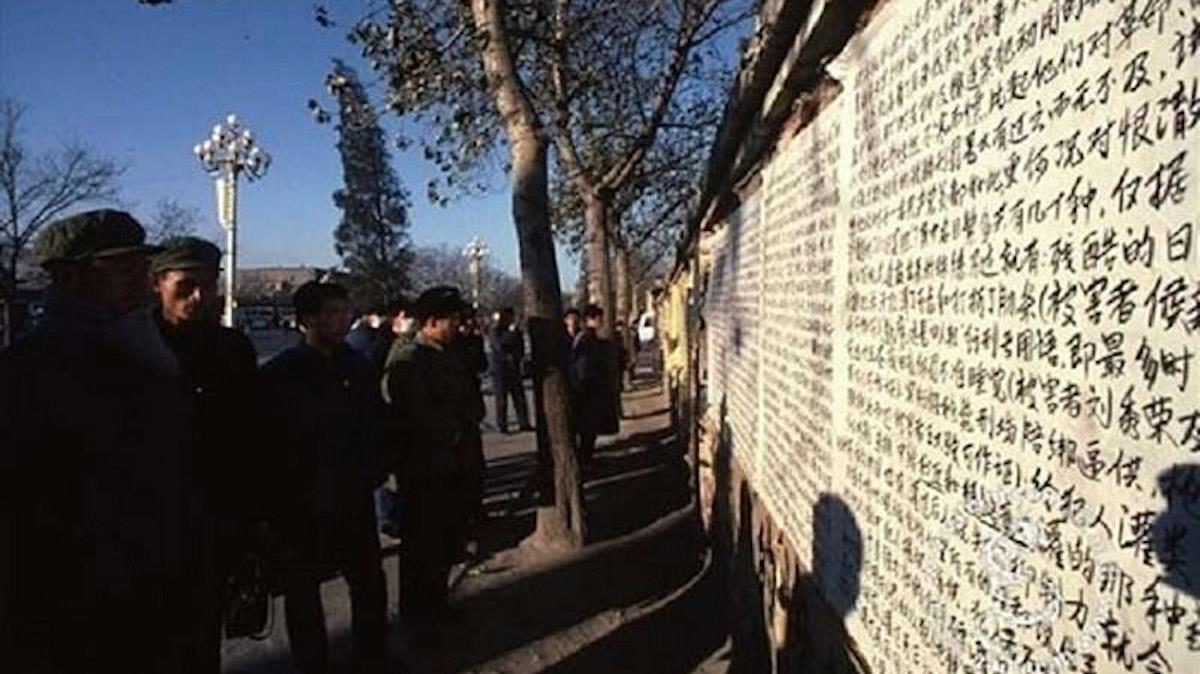

When demonstrations against the so-called“zero-Covid” policy's physical restrictions first erupted, President Xi Jinping answered with police repression, echoes of measures common to two other big outbreaks of public displeasure in the post-Mao Zedong era – the Democracy Wall Movement of the late 1970s and the mass Tiananmen Square protest in Beijing, 1989.

Xi mobilized security forces – in this case, municipal police and the paramilitary anti-unrest People's Armed Police – to break up protests, make arrests and unleash China's vast surveillance apparatus to identify troublemakers by inspecting mobile phones and internet messages.

Then, on Thursday, public health officials suddenly announced lockdown relief. Local bureaucrats would be allowed to undo restrictive measures, which had been Xi's one-size-fits-all weapon to fight the spread of the epidemic.

Vice Premier Sun Chunlan, one of the country's senior health officials, described the disease danger as fading even as a new Covid variant had emerged.

“The country is facing a new situation and new tasks in epidemic prevention and control as the pathogenicity of the Omicron virus weakens,” Sun said. “More people are vaccinated and experience in containing the virus is accumulated.”

She made no mention of zero-Covid goals and tactics. Limits on movements in Shanghai and Guangzhou, major city centers of anti-lockdown demonstrations, were immediately lifted, except on persons actually infected. Restrictions in districts of other cities, including Beijing, were also eased.

Democracy Wall. Photo: Wei Jingsheng / Free Asia

The stick-and-sudden-carrot approach has been a common practice of dealing with public unrest since the 1970s, after the fall of Mao and the rise of supposedly pragmatic, less ideological leadership. The Democracy Wall Movement, named after a kind of political bulletin board that stood in central Beijing, was tolerated for a few years.

But then dissidents and common citizens were arrested for demanding deep political changes. The Democracy Wall was dismantled; another was set up in a park three miles away. Whoever wanted to leave a message would have to register with name and address.

The carrot came in the form of capitalist-style economic freedoms. Maximum leader Deng Xiaoping appointed Zhao Ziyang, an economic reformer, to head the Chinese Communist Party and usher in free market economic changes that included the monumental dismantling of communal farms, putting the land into private hands.

There was, however, one caveat: Political leadership of the party and formal acceptance of Marxist-Leninist rule had to be maintained.

In 1989, thousands of demonstrators occupied Beijing's iconic Tiananmen Square, just outside the Forbidden City, to protest Communist Party corruption, inflation and limits on free speech. Horrified by the fervor of the mostly student protestors and wary of igniting changes such as were occurring in the Soviet Union under Mikhail Gorbachev, Deng dispatched the Peoples Liberation Army to clear the square.

In the early morning of June 4, hundreds of demonstrators camping in the square were killed – some shot, some run over by tanks. Dozens of activists were jailed; others escaped into exile.

Shortly afterward, Deng doubled down on economic reform, persuaded that increased prosperity would cement Communist rule and promote his drive to build China into an economic powerhouse. Zhao Ziyang, who had supported the Tiananmen protestors, was placed under house arrest for life. Zhao's replacement, Jiang Zemin, kept to the straight and narrow of party rule while promoting capitalist-style growth and foreign investment.

Since the 1980s, scattered protests have taken place in response to various, if familiar, problems: government corruption, heavy-handed controls and economic problems. But the way that the current anti-Covid protests developed is new, at least for China, and might herald a period of public discourse within Xi's tightly controlled political galaxy.

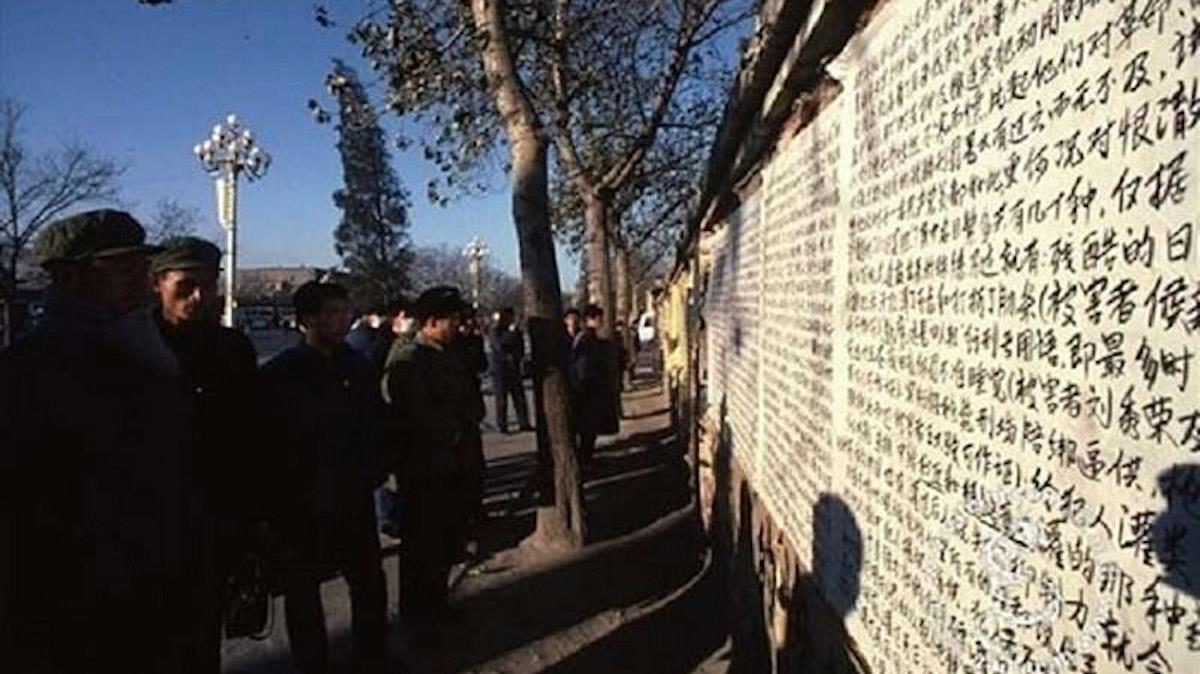

Chinese protesters air their views on the government's 'zero-Covid' restrictions. Image: Screengrab / BBC

The current demonstrations erupted in a world of mobile phones and the internet. Images of a burning apartment building in Xinjiang, which received scant attention in the state media, were spread on cell phone videos.

What the government tried to downplay the event, millions of Chinese could ponder on their own, opening the way for spontaneous response. People in a variety of cities heard that doors in the flaming building were bolted shut by government order or that firefighters were obstructed by roadblocks intended to limit the spread of Covid. The fire disaster become a metaphor for the frustrations with zero-Covid felt by all who had been confined to their apartments for weeks or months, unable to move or work.

The new, dispersed nature of protests makes them harder to tamp down. After two months of tolerance, Tiananmen was cleared by military force in a night. Diffuse and apparently leaderless anti-Covid-restriction protests are harder to counter, at least without quick compromise.

Xi faces a dilemma. He bet on zero-Covid physical control rather than keeping up with boosters, especially among the elderly, and importing foreign-made mRNA vaccines. It's not clear whether the sudden change of heart on lockdowns – and a concurrent step up in vaccinations – will work, or whether it is just a way to place responsibility for future failure on local officials.

“Citizens are exhausted,” wrote Yves Tiberghien, a professor of political science at Canada's University of British Columbia. “Omicron virus is set to run rampant. Whether China can find a pragmatic and peaceful way out of its zero-Covid approach remains an open question.”

Xi himself seems not fully confident that Thursday's lessening of restrictions is enough to quell discontent. He has issued an“emergency response” decree of censorship, including a crackdown on virtual private networks and other means of bypassing online censorship.

It appears that, beyond a Covid surge, the possibility of an epidemic spread of information outside Xi's Great Firewall of communication control is also a source of alarm.

Comments

No comment